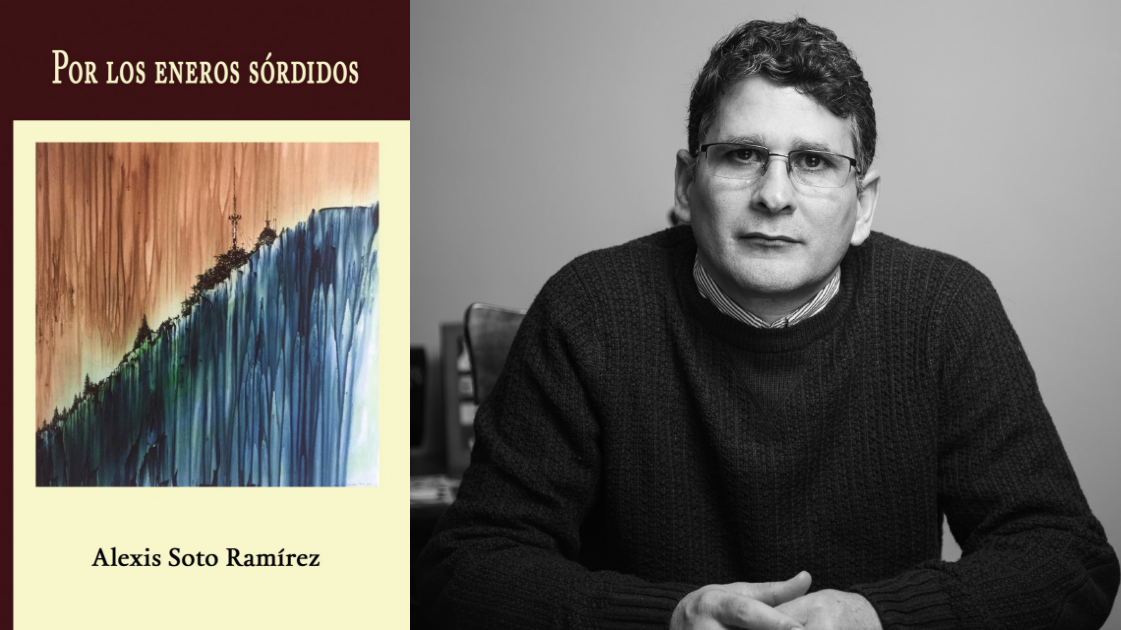

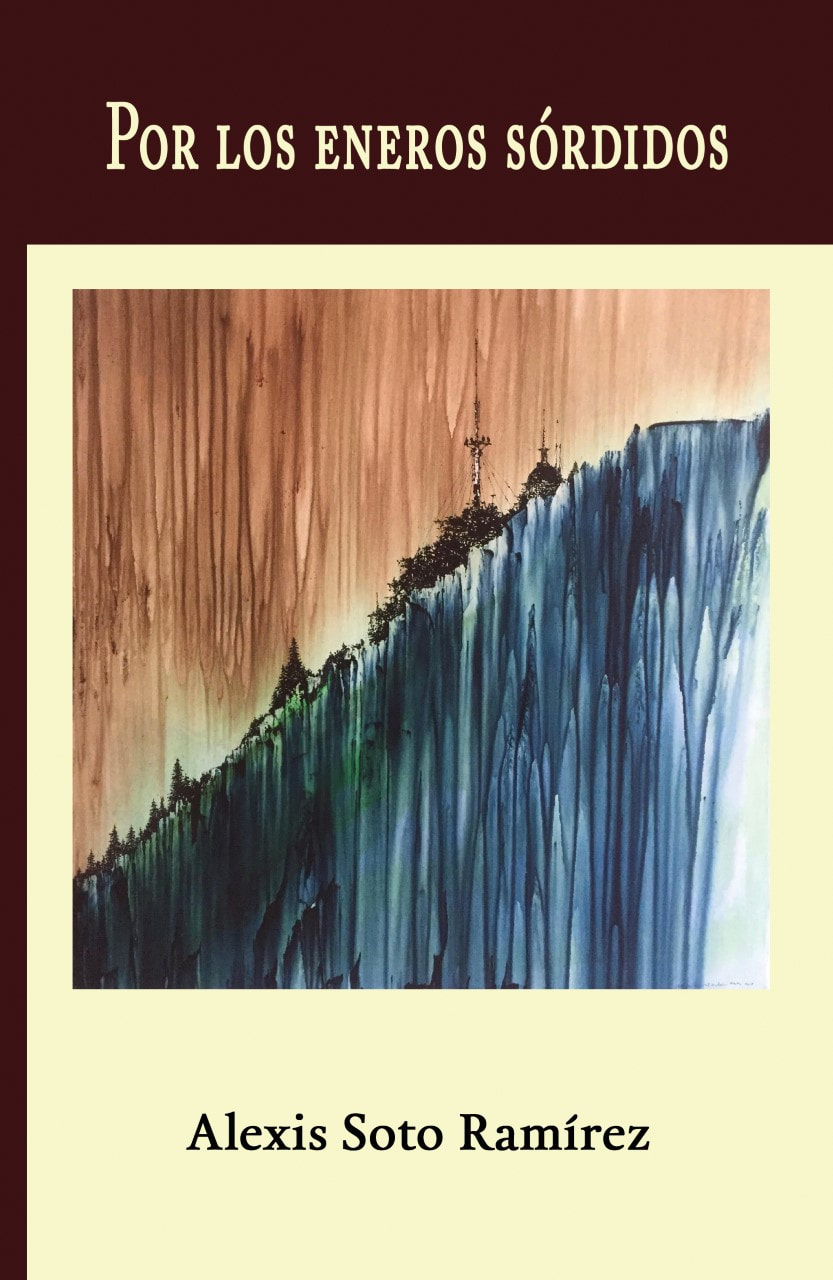

Por los eneros sórdidos

Alexis Soto Ramírez

|

The poetry collection of this outstanding Cuban poet could be called, with good reason, a baroque banquet given that it incorporates all the elements of this aesthetics and path of understanding human existence: mirrors, the grotesque, humor, sensuality, death, existential crisis, exuberance, awareness and reflexivity of language and art. Being baroque is an exuberant way of living: “la desmesura deviene lo grotesco / el caracol se enamora de sí mismo y perece / sin salir jamás de su casa / los griegos conocían los peligros de la hybris” (“lo grotesco” 66).

As José Antonio Michelena Gutiérrez points out in his splendid foreword, Soto Ramírez’s poetry can be traced to the Orígenes group of Lezama Lima. Thus, the dialogue with the Caribbean baroque literary tradition is evident: even the last poem of the book (“me vi cayendo de manteles”) incorporates an epigraph by the author of Paradiso (1966) from his famous poem about death and the divine, “Una oscura pradera me convida.” With great subtlety and sensuality the poetic voice of “me vi cayendo de manteles” is delivered on that final journey, which is also an experience of poetic language and baroque feeling: “me vi cayendo de manteles / con las manos atadas a lo oscuro / sin remordimiento ni gozo / ni destello / nadie invitó a la enredadera / salvaje girasol mi cuello / y mis espaldas flagelando” (“me vi cayendo de manteles” 98). At the same time, you don't have to be or feel like a literary expert or connoisseur to understand these poetics as baroque. The baroque, its language and its liberating existential transgression, as great writers such as Severo Sarduy, Guillermo Cabrera Infante and Reinaldo Arenas have well commented and experienced, is inherent (Immanent) to the Caribbean and, specifically, to the Cuban DNA. The reader will find in this collection of poems a treat, a delight to the senses, a festival of words: “la zarpa del tigre su aliento halógeno / piedra o hueso lunar sembrados en lo ignoto / la correspondencia de la sal acumulada / los espantosos meandros de la miseria” (“la paloma” 70). |

The poetic voice meticulously elaborates a world made of words, where the social and political commentary is relevant, and there is also room to laugh, to undress, to eat, to feel, and to allow the reader to be possessed by an existence that overwhelms and seduces: “goyesco aliento como de pájaros el aire / no de silicato / sino de lentos sinsabores / como regresa al acordeón / una y otra vez el mismo aire / así culmina cada rostro su exterminio (“como de pájaros el aire” 32).

Why the baroque? Because the baroque is death and life in language, because the baroque is the pain and joy of the flesh and all that is the poetry of Alexis Soto Ramírez, who had to undergo the death of the raft in the sea, fleeing from tyranny to find freedom in other lands.

Why the baroque? Because the baroque is death and life in language, because the baroque is the pain and joy of the flesh and all that is the poetry of Alexis Soto Ramírez, who had to undergo the death of the raft in the sea, fleeing from tyranny to find freedom in other lands.

Alexis Soto Ramírez (La Habana, Cuba, 1967) is the author of Estados de calma (Ediciones Extramuros, 1993), Turbios celajes intrincados (Ediciones Lenguaraz, 2016), Oscuro impostergable o la circunstancia de la hormiga (Ediciones Lenguaraz, 2016), La moda albana (Ediciones Lenguaraz, 2019), and Por los eneros sórdidos (Ediciones La Mirada, 2021). He lives in Ojochal, Costa Rica.

Por los eneros sórdidos (2021) was published by Ediciones La Mirada. Click here to purchase.

Por los eneros sórdidos (2021) was published by Ediciones La Mirada. Click here to purchase.

Comment Box is loading comments...

|

|