Viva Cuba Libre: Evangelina Cisneros & the Fight for Cuban Independence

By Chanel Cleeton

Growing up in a Cuban-American household, my family often spoke of Cuba, of their memories, of their hope that when Fidel died their exile would end and they would be able to return home. They spoke of their love for their country, the happy memories of their lives there, and in the food they cooked, the language we spoke, the stories they told, they created their own version of Cuba in exile to pass down to generations. As I grew older and began exploring my Cuban heritage more, as I yearned to understand more about where I come from and the experiences of my ancestors, I began to realize that while much of my family’s stories centered around the revolution and its aftermath—the eight years they lived under Fidel’s regime before boarding a Freedom Flight to the United States—I knew much less about more distant Cuban history. While growing up straddling a hyphenated identity I learned about American history going back centuries in school, it always felt as though as there was a piece of my identity that was missing, a piece of my family’s history—my history—that was incomplete. As I grew older, I began asking more about events before my grandparents’ time, events my great-grandparents and their ancestors may have lived through. But as with so much in exile, the answers I sought weren’t necessarily available, documents left behind in Cuba whereabouts unknown, pieces of our history buried in a backyard waiting for our return, family members passed on, more questions than answers.

Writing historical fiction often feels like playing detective, following the historical record for clues, and hopefully, answers—and while I couldn’t necessarily recreate my family’s past going back centuries, I could piece together Cuba’s past, could try to understand the events that led up to my family fleeing their homeland, coming to the United States as refugees. I could attempt to understand this revolution that came to be and had such a lasting impact on my family and so many others. With each book I’ve written since I first began exploring my Cuban identity in Next Year in Havana, it feels like I’ve gotten a little closer to that understanding I’ve craved, my research filling in gaps of my knowledge of Cuban history and giving me a deeper and broader appreciation of the sacrifices and trials my family and so many others faced.

|

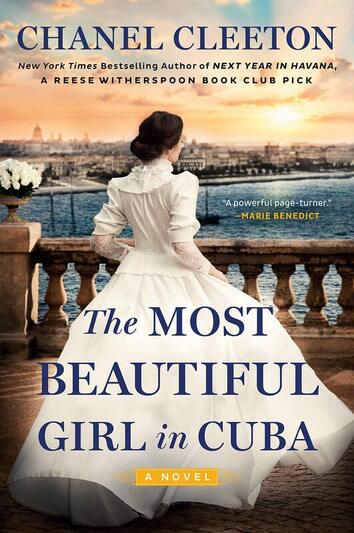

With my new book, The Most Beautiful Girl in Cuba, I traveled farther back in time than I ever have before—to 1896 and the Cuban fight for independence from Spain. My great-grandparents would have lived through this time in Cuba, and I found myself wondering what their lives would have been like. It’s a question that I won’t ever be able to answer for sure, but researching and writing the book, I constantly found myself thinking about it, realizing I was trying to map my own history as I was following in my characters’ footsteps.

The desire to write about this moment in Cuban history was sparked by a research trip to the Florida Keys for my last book, The Last Train to Key West, and an impromptu visit to the San Carlos Institute—a Cuban heritage center—and the USS Maine Memorial. As I learned more about the Cuban fight for independence from Spain and the Spanish-American War, I realized how little I knew about it, and what I did know was from bits and pieces that came to me in school—“Remember the Maine”—and covered the American perspective. I wanted to know what it would have been like in Cuba. I wanted to know what it would have been like for my ancestors. |

As I began researching The Most Beautiful Girl in Cuba, I was struck once again by how hard Cuba has fought for independence and then for its own autonomy. How much has been sacrificed and hoped for, and how much the promise of self-determination has been denied, how Cuba’s fortunes have been shaped by foreign powers first through colonialism and then through the immense influence other countries have wielded over it. In a way, it felt like the cry of “Viva Cuba Libre” that was echoed when Cuba fought for independence from Spain and the sentiment of “Viva Cuba Libre” that I heard as the daughter and granddaughter of exiles was a promise for many that would go unfulfilled. And in that hope, that love of country, that passion I found a familiar chord.

While I was researching The Most Beautiful Girl in Cuba, I came across a mention of a Cuban revolutionary named Evangelina Cisneros in one of the pieces I was reading about the leadup to the Spanish-American War. In the historical fiction I write, I gravitate toward stories of ordinary people whose lives are changed in extraordinary times, and in Evangelina Cisneros, I found the epitome of such a life. At eighteen years old, she was living in exile on the Isle of Pines with her father—who had been sent there after attempting to join the revolutionary effort against the Spanish—when she rejected the unwanted advances of the Spanish colonel in charge of the Isle of Pines. She was sent to the Casa de Recogidas, a notorious women’s prison in Havana, and her plight eventually reached the ears of William Randolph Hearst, the infamous publisher of one of the most influential newspapers in New York City, the New York Journal. In his quest to upend Joseph Pulitzer’s reign on journalism in the city, Hearst saw an opportunity to use Evangelina as a rallying cry to garner support for U.S. intervention in the conflict between Cuba and Spain. By splashing Evangelina’s story all over his newspaper and proclaiming her “The Most Beautiful Girl in Cuba,” it was also a chance for him to increase his circulation and fulfill his goal of being the most widely read and influential newspaper in the city.

While I was researching The Most Beautiful Girl in Cuba, I came across a mention of a Cuban revolutionary named Evangelina Cisneros in one of the pieces I was reading about the leadup to the Spanish-American War. In the historical fiction I write, I gravitate toward stories of ordinary people whose lives are changed in extraordinary times, and in Evangelina Cisneros, I found the epitome of such a life. At eighteen years old, she was living in exile on the Isle of Pines with her father—who had been sent there after attempting to join the revolutionary effort against the Spanish—when she rejected the unwanted advances of the Spanish colonel in charge of the Isle of Pines. She was sent to the Casa de Recogidas, a notorious women’s prison in Havana, and her plight eventually reached the ears of William Randolph Hearst, the infamous publisher of one of the most influential newspapers in New York City, the New York Journal. In his quest to upend Joseph Pulitzer’s reign on journalism in the city, Hearst saw an opportunity to use Evangelina as a rallying cry to garner support for U.S. intervention in the conflict between Cuba and Spain. By splashing Evangelina’s story all over his newspaper and proclaiming her “The Most Beautiful Girl in Cuba,” it was also a chance for him to increase his circulation and fulfill his goal of being the most widely read and influential newspaper in the city.

|

From her imprisonment in Recogidas to her subsequent jailbreak at the hands of Hearst’s reporters and escape from Cuba to her tour of the United States where she was feted by parades and large-scale public gatherings attended by tens of thousands, Evangelina Cisneros instantly became an international celebrity. While much was written about Evangelina, so much of her life was shaped by the media and used for their own purposes, that it was difficult to get a sense of who she really was. Even her “autobiography” which I used as my primary source for her storyline in The Most Beautiful Girl in Cuba, was published by William Randolph Hearst and likely ghostwritten by members of his staff.

While there were many questions to be asked and attempted to answer in the telling of Evangelina’s role in the Cuban fight for independence from Spain and the Spanish-American War, what became evident was Evangelina’s love for her country. Her patriotism and her dreams of a free and independent Cuba, as well as her and her family’s role in fighting for Cuban independence, formed the heart of her story. In fact, when asked how she would like her story to end she said with the cry of “Viva Cuba Libre,” a sentiment I honored in The Most Beautiful Girl in Cuba, and a desire that resonates with so many exiles. In a way, Evangelina’s story was also Cuba’s story, and that of so many who have aspired for a free Cuba. I was struck by the strength of the Cuban people and of that fierce sentiment of hope that has endured for centuries that I wrote about in my first novel, Next Year in Havana. |

Writing about Evangelina and the fight for independence didn’t give me the answers I sought about my own family history, and in this, it seems that some things are perhaps lost to time and revolution. But it did teach me more about my Cuban heritage. It gave me a deeper appreciation for the strength of my family’s love for their homeland and their patriotism, and when I hear the cry of “Viva Cuba Libre” I think of a cry that has resonated for centuries, of all who have sacrificed and placed their hopes in the dream of a free Cuba.

Comment Box is loading comments...

|

|