Three Questions for Alejandro Varela

Regarding His Debut Novel, The Town of Babylon

By Daniel A. Olivas

Alejandro Varela (he/him) has written for many publications including Boston Review, Harper’s, The Rumpus, The Brooklyn Rail, The Offing, Apogee Journal, and The Point, among other places. His short-story collection, The People Who Report Stress, will be published by Astra House in 2023. Currently based in New York, his graduate studies were in public health.

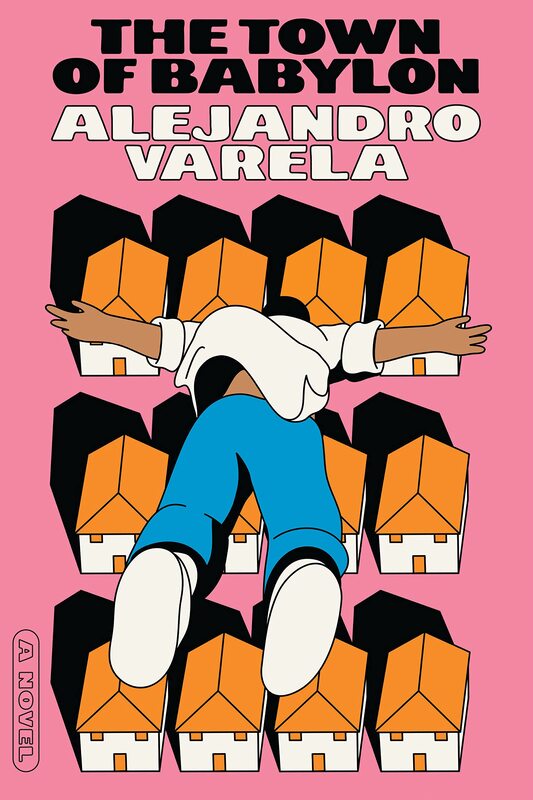

Varela’s debut novel, The Town of Babylon (Astra House), was released earlier this year to universal acclaim. It follows Andrés who returns to his boyhood town because his father has fallen ill. With a marriage that is rocky after his husband’s infidelitiy, Andrés encounters ghosts from his past in the form of a his first love, old friends, family members, and questions about the death of his brother. Publishers Weekly called his novel a “dazzling debut” and “an incandescent bildungsroman.” Book Riot dubbed it “a richly textured portrait of ordinary queer life.” And Varela’s novel was deemed one of the most anticipated books of 2022 by BuzzFeed, LitHub, Electric Literature, LGBTQ Reads, and Latinx in Publishing.

And there is good reason for such effusive praise. The Town of Babylon is a big-hearted, intricate, and daring debut novel that creates a fully-realized, imperfect hero who confronts our country’s great failings while discovering the fragile beauty that lurks beneath the surface of human connections. There is an assuredness to Varela’s writing, a quality usually observed in authors who have a dozen books to their name. Simply put, this is perfectly crafted novel from a truly talented writer.

Varela kindly agreed to answer a few questions about The Town of Babylon.

DANIEL A. OLIVAS: The Town of Babylon is an ambitious debut novel with a large and vital cast of characters that even includes the town itself. How did you decide to tell your story in such a wide-lens fashion, and did you consider other approaches?

ALEJANDRO VARELA: Before I started writing the book, I took a reading sabbatical of sorts. I read (maybe overread) a host of novels. And the three that stayed with me were The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison, The Dispossessed by Ursula Le Guin, and In the Time of Butterflies by Julia Alvarez. I hadn’t been looking for anything specific when I set out to read these books. I wanted only to be in the mindset of the novel form since I’d spent the previous years writing short stories exclusively. Each of these three books weren’t only exquisitely written, they also gave me the permission, if you will, to create a work of depth and breadth. They gave me the confidence to play with time and narrators. But most importantly, they told me it was okay to explore motivations and circumstances, so that I could tell a more complete story. Because of my public health background, I’m always thinking about the systems and histories that contribute to our behaviors. But I wasn’t sure if I could pull off that sort of sociological writing. The Bluest Eye let me cut loose. Frankly, I think of Morrison as a public health writer, someone concerned with exposing the ways in which society dictates the actions of individuals.

I wanted to tell the stories of a few people, but I also wanted to tell the story of a town. The town in the book was based on Roseto, PA, which factored heavily in my public health education. Research conducted in that town found that cohesion and camaraderie was more deterministic of a community’s positive health outcomes than diet, exercise, genetics, etc. That was the story I wanted to tell from the outset. I considered telling it linearly, but one narrator would have been limited in their abilities. Andrés was already a know-it-all, he couldn’t also have been a historian of a town that he detested. It would have been a harder sell, and it would have undercut the omniscient narrator’s revelations throughout.

OLIVAS: Your main character, Andrés, is forced to confront his past when he returns to the town of his youth to attend a high school reunion. Andrés bravely--though not always voluntarily--attempts to find the truth beneath the public facades of his friends, family and even himself. In some ways, each of the characters touches upon different aspects of Andrés's identities as a son, brother, lover, professional, Gay man, and member of the Latinx community. Can you talk about your crafting of these many mirrors that are held up to Andrés?

VARELA: In this way, I can relate to Andrés. I am a person with several political identities, who has often had to code switch, that is, think twice about what parts of me come to the forefront depending on my audience. Too gay in straight spaces? Too queer in gay spaces? Too working-class in middle-class spaces, and vice versa? Too brown in white spaces? With age, I’ve gotten better at accepting the tapestry, but it’s taken a lot of time and energy, and consequently, sacrificing a degree of power to accommodate others. Andrés grapples with these contradictions and intersections, and I enjoyed empowering him. He is someone who thinks twice (and thrice) about social interactions, but I tried to create a character who wasn’t defeated by the prospect of being himself. It’s a journey, in which we get to see him live his various identities, but ultimately he brings his entire person to the town. I hope in the process, the uninitiated reader gets a sense of the labor involved in being many things in a society that loves its binaries and thrives on assimilation.

OLIVAS: You address issues of race and sexual identity that Andrés and other characters face as they navigate through life in this country. You also explore Andrés's own bigotry which, much to his surprise, arose with his husband when they were dating. Though you bring great nuance to your grappling with these issues, is there a central message you were attempting to convey?

Varela’s debut novel, The Town of Babylon (Astra House), was released earlier this year to universal acclaim. It follows Andrés who returns to his boyhood town because his father has fallen ill. With a marriage that is rocky after his husband’s infidelitiy, Andrés encounters ghosts from his past in the form of a his first love, old friends, family members, and questions about the death of his brother. Publishers Weekly called his novel a “dazzling debut” and “an incandescent bildungsroman.” Book Riot dubbed it “a richly textured portrait of ordinary queer life.” And Varela’s novel was deemed one of the most anticipated books of 2022 by BuzzFeed, LitHub, Electric Literature, LGBTQ Reads, and Latinx in Publishing.

And there is good reason for such effusive praise. The Town of Babylon is a big-hearted, intricate, and daring debut novel that creates a fully-realized, imperfect hero who confronts our country’s great failings while discovering the fragile beauty that lurks beneath the surface of human connections. There is an assuredness to Varela’s writing, a quality usually observed in authors who have a dozen books to their name. Simply put, this is perfectly crafted novel from a truly talented writer.

Varela kindly agreed to answer a few questions about The Town of Babylon.

DANIEL A. OLIVAS: The Town of Babylon is an ambitious debut novel with a large and vital cast of characters that even includes the town itself. How did you decide to tell your story in such a wide-lens fashion, and did you consider other approaches?

ALEJANDRO VARELA: Before I started writing the book, I took a reading sabbatical of sorts. I read (maybe overread) a host of novels. And the three that stayed with me were The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison, The Dispossessed by Ursula Le Guin, and In the Time of Butterflies by Julia Alvarez. I hadn’t been looking for anything specific when I set out to read these books. I wanted only to be in the mindset of the novel form since I’d spent the previous years writing short stories exclusively. Each of these three books weren’t only exquisitely written, they also gave me the permission, if you will, to create a work of depth and breadth. They gave me the confidence to play with time and narrators. But most importantly, they told me it was okay to explore motivations and circumstances, so that I could tell a more complete story. Because of my public health background, I’m always thinking about the systems and histories that contribute to our behaviors. But I wasn’t sure if I could pull off that sort of sociological writing. The Bluest Eye let me cut loose. Frankly, I think of Morrison as a public health writer, someone concerned with exposing the ways in which society dictates the actions of individuals.

I wanted to tell the stories of a few people, but I also wanted to tell the story of a town. The town in the book was based on Roseto, PA, which factored heavily in my public health education. Research conducted in that town found that cohesion and camaraderie was more deterministic of a community’s positive health outcomes than diet, exercise, genetics, etc. That was the story I wanted to tell from the outset. I considered telling it linearly, but one narrator would have been limited in their abilities. Andrés was already a know-it-all, he couldn’t also have been a historian of a town that he detested. It would have been a harder sell, and it would have undercut the omniscient narrator’s revelations throughout.

OLIVAS: Your main character, Andrés, is forced to confront his past when he returns to the town of his youth to attend a high school reunion. Andrés bravely--though not always voluntarily--attempts to find the truth beneath the public facades of his friends, family and even himself. In some ways, each of the characters touches upon different aspects of Andrés's identities as a son, brother, lover, professional, Gay man, and member of the Latinx community. Can you talk about your crafting of these many mirrors that are held up to Andrés?

VARELA: In this way, I can relate to Andrés. I am a person with several political identities, who has often had to code switch, that is, think twice about what parts of me come to the forefront depending on my audience. Too gay in straight spaces? Too queer in gay spaces? Too working-class in middle-class spaces, and vice versa? Too brown in white spaces? With age, I’ve gotten better at accepting the tapestry, but it’s taken a lot of time and energy, and consequently, sacrificing a degree of power to accommodate others. Andrés grapples with these contradictions and intersections, and I enjoyed empowering him. He is someone who thinks twice (and thrice) about social interactions, but I tried to create a character who wasn’t defeated by the prospect of being himself. It’s a journey, in which we get to see him live his various identities, but ultimately he brings his entire person to the town. I hope in the process, the uninitiated reader gets a sense of the labor involved in being many things in a society that loves its binaries and thrives on assimilation.

OLIVAS: You address issues of race and sexual identity that Andrés and other characters face as they navigate through life in this country. You also explore Andrés's own bigotry which, much to his surprise, arose with his husband when they were dating. Though you bring great nuance to your grappling with these issues, is there a central message you were attempting to convey?

|

VARELA: Andrés’s husband, Marco, is possibly my least explored protagonist. In part, I was afraid to overextend the narrative; I also didn’t want to spend time in the city. Marco couldn’t travel with him to the suburbs because it would have been a different story. So I had to get rid of him, hence the business trip to Namibia. The question is, why did I include him to begin with? Andrés needed a catalyst. Actually, he needed a barnstormer of a reason for why he would endeavor into a town that he’d avoided for 20 years. A fractured marriage was a dislocating enough force to make someone act in ways they might not otherwise.

The issues of anti-Black racism within the Latinx/e community are real and woefully under-addressed. Marco, who is Black Dominican, and Henry, who is darker skinned than Andrés, were two avenues to discuss how oppressed people oppress people too. The hierarchies amongst our people are akin to the white supremacist ones that define our society at large. In fact, our histories of colonization have embedded racist ideologies and lenses into our communities. The scarcity mode of capitalism and its accompanying politics of xenophobia have turned immigrants into anti-immigrants, targets of racism into perpetrators of racism, community-minded people into individualists. I could have written a book where all the villains were white, but I found it interesting to examine the forces that can make anyone self-hating. My hope, too, was that Andrés’s assessment of his own prejudices would allow readers to see that there can be growth through exploration, solidarity, and humility. The interiority (sometimes tortured) of my protagonists is a very real consequence of marginalization. There are many people like Andrés in this world. I’m related to several, friends with many, colleagues with a few others, and I might be one too. We are legion, and our society should reckon with the psychological burden that an ever-greater portion of its people carry. The further we’re removed from one another, from the center, and from self-determination, the more we retreat to our own psyches. |

When you purchase a book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission and so do independent book stores.

|

Comment Box is loading comments...

|

|