The Origins of La Llorona

Many of us grew up listening to stories about La Llorona. As we grew older, we began to question the origin of such legend. Some believe La Llorona was a native woman who had children with a Spaniard during colonial times and decided to drown her children after he abandoned her. Others say that La Llorona is La Malinche who returns with remorse because of her “betrayal” towards indigenous people. There are many versions about the origin of La Llorona, but what do the earliest historical texts say about the mysterious woman dressed in white who cries for her children?

|

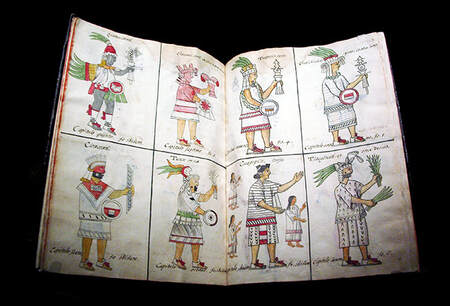

The first texts that mention a woman with the characteristics of La Llorona are located in the Florentine Codex, also known as Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España. The Florentine Codex is composed of twelve books and was put together in 1577 according to the Laurentian Library of Florence where it is currently located. Some of the text in its books, however, can be dated earlier. Book twelve was originally written in Náhuatl language in 1555 according to Fray Bernardino de Sahagún. Mexican historian Miguel León-Portilla calls this section of the Florentine Codex, Testimonios de los informantes de Sahagún. Native students from Tlatelolco collected first-hand testimonies from native elders with the supervision of Sahagún. [1]

|

Florentine Codex

|

In book twelve of the Florentine Codex, native elders stated that ten years prior to the arrival of the Spaniards, the Mexica (Aztecs) and in particular Motecuhzoma (Moctezuma II), began to witness a series of omens. These prophecies signaled the arrival of men who waged war and the downfall of Tenochtitlan. Omen number six states that a woman was heard crying and screaming at night many times, "My children, we now have to leave far away!" Other times she would say, "My children, where shall l take you?" [2] The passage is accompanied by an illustration of the native woman, crying, barefooted, and clutching her hands.[3]

Florentine Codex: Book 12

The first and eighth books of the Florentine Codex indicate that the woman crying at night, worried for her children, is none other than the goddess Cihuacóatl, whose name means "serpent woman". In chapter six of the first book, Sahagún narrates some apparitions by Cihuacóatl. He describes her attire as "white, with her hair as if she had horns crossed above her forehead." The original version of this passage, written in Náhuatl, states that Cihuacóatl was covered in “chalk” and would “appear at night dressed in white, walking and crying”.[4] Book eight of the Florentine Codex says that a terrible famine occurred for three years during Motecuhzoma's reign prior to the arrival of the Spaniards, and "the devil who is named Cihuacóatl would appear and go around crying through the streets of Mexico.” The Náhuatl version of this passage mentions that everyone would hear her crying and saying, "My beloved children, I'm going to leave you now." The eighth book also states that during the sixth omen, a voice was heard crying and saying, "Oh, my children, we are about to be lost." The voice would also cry, "My children, where shall I take you?" At the beginning of the text describing the sixth omen, an illustration shows Cihuacóatl. She has the head of a woman, her hair combed like horns and the body of a snake.[5] Chapter two makes a terrifying assertion that took place after the conquest; Cihuacóatl ate a child that was in his crib in the town of "Azcaputzalco."[6]

Florentine Codex: Book 8

|

Stone statue of Cihuacóatl

|

There are two other texts, also from the 16th century, which mention a woman with the characteristics of La Llorona and refer to a set of pre-colonial omens, The Durán Codex and La Historia de Tlaxcala. The Durán Codex, also known as Historia de las Indias de Nueva España e Islas de Tierra Firme, is dated 1579 according to the Biblioteca Nacional de España where it is currently located.[7] The text states that Motecuhzoma summoned all of the leaders of the "barrios" and asked them to tell all of the elders that from now on they are to report to him what they see in their dreams. Motecuhzoma also asked the leaders to tell those who have a habit of wondering at night, that if they were to run into "that woman whom people say wonders at night crying and moaning, to ask her why she cries and moans."[8]

La Historia de Tlaxcala, dated 1592 according to Dr. Francisco Ramírez Santacruz and Dr. Héctor Costilla Martínez, was written by a mestizo descendant of Tlaxcaltecan nobility named Diego Muñoz Camargo. The text states that during a sixth omen, many times and for many nights, you could hear the voice of a woman crying and sobbing loudly, "Oh my children! We will now lose everything..." and other times she would say, "Oh my children, where can I take you and hide you?"[9]

|

After the arrival of the Spaniards during colonial Mexico, the story of La Llorona evolved. Today’s popular versions blames La Llorona for her own tears and exonerates the Spaniards. It does not mention the foretold destruction of Tenochtitlan and arrival of the Europeans. It is important to understand that La Llorona is not just a story or folklore, it is part of Mexico’s historical record.

Sources

[1] Portilla Miguel León, María Garibay K. Angel, and Beltrán Alberto. Visión De Los Vencidos: Relaciones indígenas De La Conquista. (México: Universidad National Autónoma de México, 2017), XX.

[2] Ibid, 6.

[3] “Historia General De Las Cosas De Nueva España Por El Fray Bernardino De Sahagún: El Códice Florentino. Libro XII: De La Conquista De México.” Historia General De Las Cosas De Nueva España Por El Fray Bernardino De Sahagún: El Códice Florentino. Libro XII: De La Conquista De México - Visor - Biblioteca Digital Mundial, https://www.wdl.org/es/item/10623/view/1/7/.

[4] Rodrigo Martínez, "Las apariciones de Cihuacóatl", historias (Revista de la Dirección de Estudios Históricos del INAH), 24, 1990, pp. 55-66.

[5] “Title: General History of the Things of New Spain by Fray Bernardino De Sahagún: The Florentine Codex. Book VIII: Kings and Lords.” WDL RSS, https://www.wdl.org/en/item/10619/view/1/27/.

[6] Ibid, 61-63.

[7] “Historia De Las Indias De Nueva España e Islas De La Tierra Firme [Manuscrito] - Durán, Diego - Manuscrito - 1579.” BIBLIOTECA DIGITAL HISPÁNICA. Accessed September 21, 2019. http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/biblioteca/Historia de las Indias de Nueva España e islas de la tierra firme /qls/Durán, Diego (1537 1587)/qls/bdh0000169486;jsessionid=71C71FFA2F6C7627F624C32AE7D40AEF.

[8]“¿La Leyenda De La Llorona Es De Origen Prehispánico?” Arqueología Mexicana, October 31, 2016. https://arqueologiamexicana.mx/mexico-antiguo/la-leyenda-de-la-llorona-es-de-origen-prehispanico.

[9] Portilla Miguel León, María Garibay K. Angel, and Beltrán Alberto. Visión De Los Vencidos, 12.

[1] Portilla Miguel León, María Garibay K. Angel, and Beltrán Alberto. Visión De Los Vencidos: Relaciones indígenas De La Conquista. (México: Universidad National Autónoma de México, 2017), XX.

[2] Ibid, 6.

[3] “Historia General De Las Cosas De Nueva España Por El Fray Bernardino De Sahagún: El Códice Florentino. Libro XII: De La Conquista De México.” Historia General De Las Cosas De Nueva España Por El Fray Bernardino De Sahagún: El Códice Florentino. Libro XII: De La Conquista De México - Visor - Biblioteca Digital Mundial, https://www.wdl.org/es/item/10623/view/1/7/.

[4] Rodrigo Martínez, "Las apariciones de Cihuacóatl", historias (Revista de la Dirección de Estudios Históricos del INAH), 24, 1990, pp. 55-66.

[5] “Title: General History of the Things of New Spain by Fray Bernardino De Sahagún: The Florentine Codex. Book VIII: Kings and Lords.” WDL RSS, https://www.wdl.org/en/item/10619/view/1/27/.

[6] Ibid, 61-63.

[7] “Historia De Las Indias De Nueva España e Islas De La Tierra Firme [Manuscrito] - Durán, Diego - Manuscrito - 1579.” BIBLIOTECA DIGITAL HISPÁNICA. Accessed September 21, 2019. http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/biblioteca/Historia de las Indias de Nueva España e islas de la tierra firme /qls/Durán, Diego (1537 1587)/qls/bdh0000169486;jsessionid=71C71FFA2F6C7627F624C32AE7D40AEF.

[8]“¿La Leyenda De La Llorona Es De Origen Prehispánico?” Arqueología Mexicana, October 31, 2016. https://arqueologiamexicana.mx/mexico-antiguo/la-leyenda-de-la-llorona-es-de-origen-prehispanico.

[9] Portilla Miguel León, María Garibay K. Angel, and Beltrán Alberto. Visión De Los Vencidos, 12.

Comment Box is loading comments...

|

|