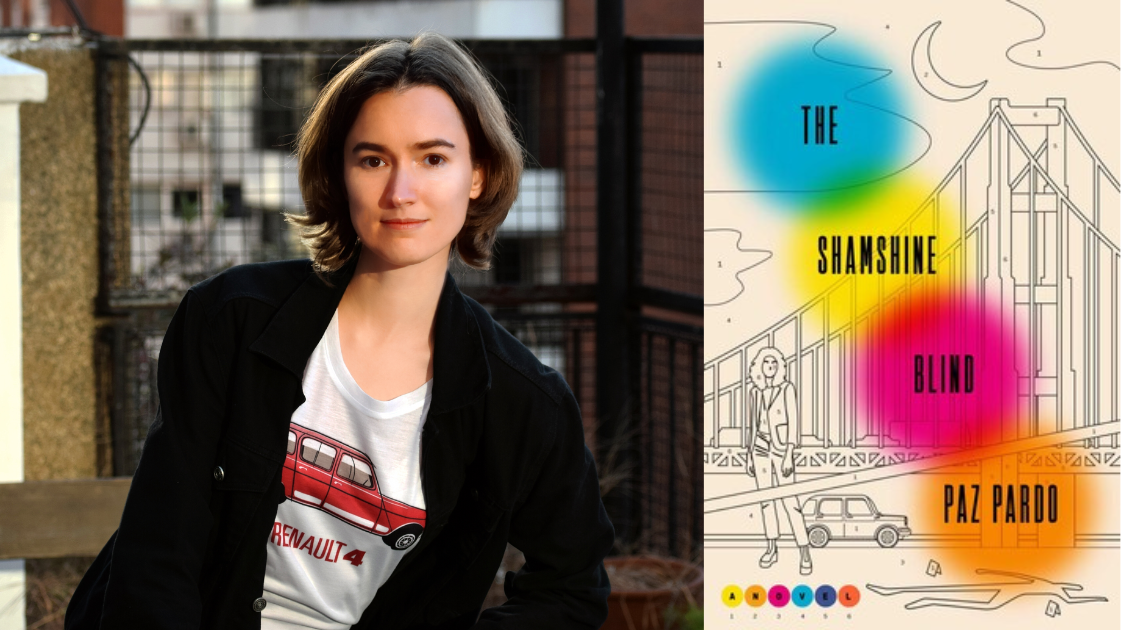

The Musicality of Noir, the Plotting of Sci-Fi:

An Interview with Paz Pardo Regarding

Her Debut Novel, The Shamshine Blind

By Daniel A. Olivas

In 1982, Argentina invaded and occupied the Falkland Islands, South Georgia, and the South Sandwich Islands leading to a ten-week undeclared war between Argentina and the United Kingdom. The conflict lasted 74 days concluding with Argentina’s surrender and return of the islands to British control. Hundreds of lives were lost on both sides. The Falklands War—known in Argentina as La Guerra de las Malvinas—had its roots in Britain’s 1833 claim to the islands following earlier French and Spanish occupation. Argentina’s loss eventually helped topple its brutal dictatorship while buttressing Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative party back in England.

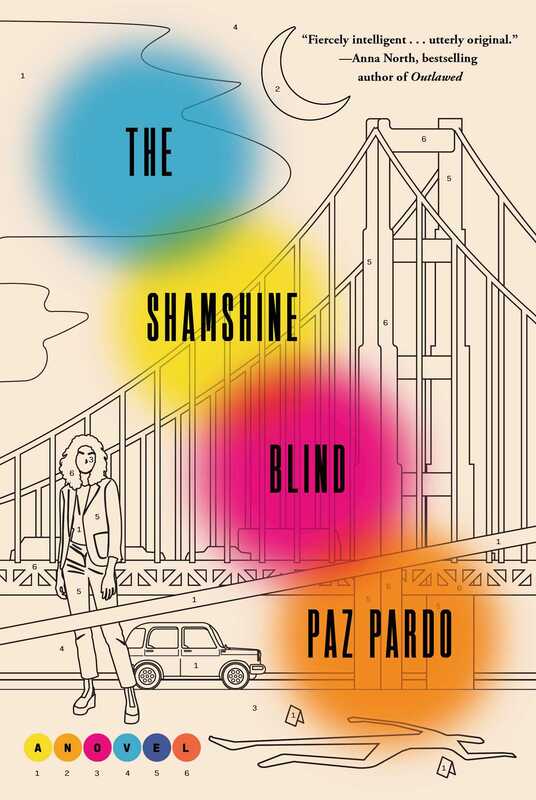

But what if Argentina had developed and deployed a secret weapon in the form of “psychopigments”—colorful chemicals that can produce any human emotion upon contact? And what if Argentina’s weaponization of emotions had defeated the United Kingdom with the domino effect of displacing the United States as a superpower? And what would this topsy-turvy world look like in 2009 after U.S. pharmaceutical companies embraced psychopigments as a moneymaking cure-all that quite naturally tempts organized crime as well as opportunistic politicians to exploit these chemicals for both profit and power?

In the hands of Paz Pardo, the result is a wildly inventive, thought-provoking, and entertaining alt-history that is equal parts science fiction and noir in her debut novel, The Shamshine Blind (Atria Books). Pardo, an Argentine-American playwright, earned her undergraduate degree from Stanford University, followed by an MFA from the Michener Center for Writers. She is the recipient of a Fulbright scholarship and has written for The New York Times’ Modern Love column. Pardo was raised in the U.S. and currently lives in Argentina with her family. At the kickoff of a national book tour, she took time to respond to a few questions about her first novel.

But what if Argentina had developed and deployed a secret weapon in the form of “psychopigments”—colorful chemicals that can produce any human emotion upon contact? And what if Argentina’s weaponization of emotions had defeated the United Kingdom with the domino effect of displacing the United States as a superpower? And what would this topsy-turvy world look like in 2009 after U.S. pharmaceutical companies embraced psychopigments as a moneymaking cure-all that quite naturally tempts organized crime as well as opportunistic politicians to exploit these chemicals for both profit and power?

In the hands of Paz Pardo, the result is a wildly inventive, thought-provoking, and entertaining alt-history that is equal parts science fiction and noir in her debut novel, The Shamshine Blind (Atria Books). Pardo, an Argentine-American playwright, earned her undergraduate degree from Stanford University, followed by an MFA from the Michener Center for Writers. She is the recipient of a Fulbright scholarship and has written for The New York Times’ Modern Love column. Pardo was raised in the U.S. and currently lives in Argentina with her family. At the kickoff of a national book tour, she took time to respond to a few questions about her first novel.

|

DANIEL A. OLIVAS: The Shamshine Blind is a delightful mashup of classic noir and science fiction tropes. Why did you decide to blur genres in this unusual way?

PAZ PARDO: I knew from early on that I wanted to write about emotions. The first seed of the idea of psychopigment came when I wrote a tongue-in-cheek recipe for pickling hope after a heartbreak, which clearly had a speculative bent. Noir and sci-fi may not seem like obvious genres for dealing with feelings, but there’s something about escapist fiction being defined by what it’s escaping from that’s always resonated with me. Personally, I find a noir narrator irresistible. As a playwright, I’m always hearing the words I’m writing—and noir has a certain musicality, a kind of compactness when read aloud that I love. Maybe it’s the genre’s history with radio drama: I remember catching an old Sam Spade episode on a college radio station, and at one point the detective refers to “a car a little longer than a hearse.” It’s a concrete image, it tells me that the character lives in a world permeated with death, there’s that small pop of alliteration—which is catnip for me. Also, it’s campily over-the-top. I love the humor that slips into these bleak worlds. The musicality of that noir language came really easily to me, but the thing that kept me going long enough to finish a first draft was my desire to figure out the plot—and the plots I know best are sci-fi. There is a history of overlap between the genres. I believe that writers like C.J. Cherryh and William Gibson draw deeply on noir language and set-ups, even if their work is set on space stations and in Blade-Runner-like cities. OLIVAS: Unlike many science fiction narratives that take place in the future, your novel is set in an alternative 2009 where the United States is a second-rate power after Argentina defeats the United Kingdom in the Falkland’s War. What inspired you to go back in time and rewrite history to tell your story? |

When you purchase a book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission and so do independent book stores.

|

PARDO: As I fleshed out the history of psychopigments, it was obvious to me that Argentina—where I live—would be the country to make a breakthrough on these psych weapons. It has a rich history of psychoanalysis; newspapers regularly opine on the oedipal complexes of politicians, and Buenos Aires has the highest density of psychoanalysts per capita in the world.

In 2012, signs had started appearing all across the country, announcing “Las Malvinas son Argentinas” (the Malvinas are Argentine). It was 30 years after the end of the Falklands War, the disaster that helped topple the brutal dictatorship. So the war was already in my head as a potential turning point in history. And once I imagined Argentina vaulted into superpowerdom, it was the obvious place to make things diverge.

OLIVAS: Your protagonist is the hard drinking, slightly damaged Psychopigment Enforcement Agent named Kay Curtida who works a beat in Daly City, which is outside a ruined San Francisco. In many ways, she fits the classic noir detective mold in the Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe tradition, but with the difference being that she is Latina. Could you talk a little about your creation of Curtida? Is there a little of you in her?

PARDO: A version of Curtida’s voice was the first thing I found in the book. It was straight-up Marlowe-light at the beginning; the process of writing the book was a process of discovering what makes her particular, what makes her her. Curtida wears the noir narrator voice like drag—in the way that any hardboiled narrator is almost in drag—I’m thinking of Jake Barnes in The Sun Also Rises saying, “It is awfully easy to be hard-boiled about everything in the daytime, but at night it is another thing.” It’s always a mask. And under that mask—spoiler alert—is the soft, tender part of her that’s vulnerable, that could be dismissed as being too emotional. I think that fear of being dismissed for our feelings is at the heart of what she and I have in common. I grew up in a mixed household—my mother is the blonde girl from Normal, Illinois; my father is Argentine. You can imagine how different their methods for navigating emotions are. I think Curtida’s family had something similar, even though both of her parents are of Colombian heritage. Her father is third-generation Floridian, focused on being assimilated, son of a veteran with a deep love of country music. Her mother, on the other hand, immigrated from Barranquilla. So they would have had very different approaches to how to deal with their feelings, when to show them, when to keep them bottled up, which I think made it very hard for Curtida to know what to do with her own sentiments.

OLIVAS: In writing this novel, did you learn anything new about yourself—as a writer—and about the craft of writing?

PARDO: Well, I learned that I could write a book! I also learned that novels are longer than plays—which sounds simple, but was hard to remember in the middle of rewrites. I’d look at my summer break in grad school and think, “I can get a whole rewrite done on the book then.” I was always wrong. It took Kirk Lynn pointing out to me that I was trying to write something that was ten plays long for me to reorient myself. Once I did that, I was able to give the work the focus it needed. On a sentence level, I could take the time to make sure that each thought fit with Curtida’s voice; on a character level, I could do the deep, slow work of peeling back her layers and discovering who she really was.

OLIVAS: What do you hope readers get from reading The Shamshine Blind?

PARDO: A good time with some thought-provoking ideas to chew over. I wanted to write a book that readers could enjoy tearing through, but with enough meat that they would keep thinking about it after they close it for the last time. A lot of people have described the book as dystopian or post-apocalyptic, but Curtida’s essentially living the equivalent of a middle-class life in Argentina or Colombia today. Sure, there’s a base for someone else’s military right down the road; sure, inflation’s in the triple digits. But she can go out and buy a burger, and in some ways, I actually think it’s utopian—she ends up in the hospital for an extended stay and never thinks about the bill! I’d love for readers to think about what it means that a book featuring the way a lot of the world lives seems like it should qualify as “post-apocalyptic.”

In 2012, signs had started appearing all across the country, announcing “Las Malvinas son Argentinas” (the Malvinas are Argentine). It was 30 years after the end of the Falklands War, the disaster that helped topple the brutal dictatorship. So the war was already in my head as a potential turning point in history. And once I imagined Argentina vaulted into superpowerdom, it was the obvious place to make things diverge.

OLIVAS: Your protagonist is the hard drinking, slightly damaged Psychopigment Enforcement Agent named Kay Curtida who works a beat in Daly City, which is outside a ruined San Francisco. In many ways, she fits the classic noir detective mold in the Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe tradition, but with the difference being that she is Latina. Could you talk a little about your creation of Curtida? Is there a little of you in her?

PARDO: A version of Curtida’s voice was the first thing I found in the book. It was straight-up Marlowe-light at the beginning; the process of writing the book was a process of discovering what makes her particular, what makes her her. Curtida wears the noir narrator voice like drag—in the way that any hardboiled narrator is almost in drag—I’m thinking of Jake Barnes in The Sun Also Rises saying, “It is awfully easy to be hard-boiled about everything in the daytime, but at night it is another thing.” It’s always a mask. And under that mask—spoiler alert—is the soft, tender part of her that’s vulnerable, that could be dismissed as being too emotional. I think that fear of being dismissed for our feelings is at the heart of what she and I have in common. I grew up in a mixed household—my mother is the blonde girl from Normal, Illinois; my father is Argentine. You can imagine how different their methods for navigating emotions are. I think Curtida’s family had something similar, even though both of her parents are of Colombian heritage. Her father is third-generation Floridian, focused on being assimilated, son of a veteran with a deep love of country music. Her mother, on the other hand, immigrated from Barranquilla. So they would have had very different approaches to how to deal with their feelings, when to show them, when to keep them bottled up, which I think made it very hard for Curtida to know what to do with her own sentiments.

OLIVAS: In writing this novel, did you learn anything new about yourself—as a writer—and about the craft of writing?

PARDO: Well, I learned that I could write a book! I also learned that novels are longer than plays—which sounds simple, but was hard to remember in the middle of rewrites. I’d look at my summer break in grad school and think, “I can get a whole rewrite done on the book then.” I was always wrong. It took Kirk Lynn pointing out to me that I was trying to write something that was ten plays long for me to reorient myself. Once I did that, I was able to give the work the focus it needed. On a sentence level, I could take the time to make sure that each thought fit with Curtida’s voice; on a character level, I could do the deep, slow work of peeling back her layers and discovering who she really was.

OLIVAS: What do you hope readers get from reading The Shamshine Blind?

PARDO: A good time with some thought-provoking ideas to chew over. I wanted to write a book that readers could enjoy tearing through, but with enough meat that they would keep thinking about it after they close it for the last time. A lot of people have described the book as dystopian or post-apocalyptic, but Curtida’s essentially living the equivalent of a middle-class life in Argentina or Colombia today. Sure, there’s a base for someone else’s military right down the road; sure, inflation’s in the triple digits. But she can go out and buy a burger, and in some ways, I actually think it’s utopian—she ends up in the hospital for an extended stay and never thinks about the bill! I’d love for readers to think about what it means that a book featuring the way a lot of the world lives seems like it should qualify as “post-apocalyptic.”

Comment Box is loading comments...

|

|