The Inheritance

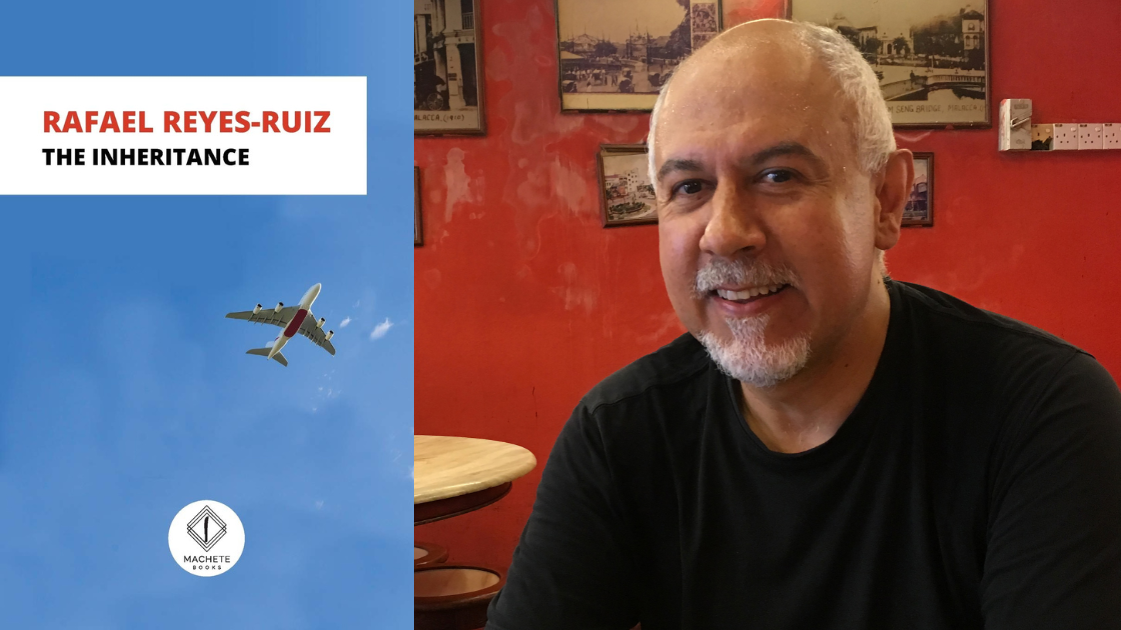

Rafael Reyes-Ruiz

|

When you purchase a book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission and so do independent book stores.

|

Rafael Reyes-Ruiz was born in Colombia, received his PhD in the United States, and worked in Japan as well as the United Arab Emirates. This combination pays dividends in his latest novel, The Inheritance. The novel’s international arc blooms into an ethnographically inflected detective story about a seemingly mundane object. The Inheritance (published in English and in Spanish editions) begins in medias res, in the epitome of putatively free movement that is in fact highly controlled circulation, the airport. The first page opens with the protagonist Tony’s arrival in Dubai. As Tony gets set up, an organized crime syndicate enters the scene: Tony has fled Tokyo because of an unpaid debt to the yakuza. In a stroke of globalized predestination, we later learn that Tony’s former lover and business partner, Adriana, follows a different itinerary but also ends up in Dubai. While the two seek to build new (and separate) lives in the Middle East, the mystery plot thickens and we wend our way through backroom dealings and foreigners’ lives in this cosmopolitan city. Tony’s and Adriana’s stories are part of an international tapestry with anecdotes such as a Turkish man who argues with a Colombian-American about politics in Portugal, believing the latter to be Kurdish. Along the way, as befits what we might term a Latinx global detective novel, we are regaled with doublings, mercenaries, dashes of sexual intrigue, oil money, dazzling skyscrapers, a chance meeting in Goa, lawyerly misdeeds, a car chase, and myriad references to the seventh art. Throughout, Reyes-Ruiz explores permutations of belonging—beyond nationality, the text reminds us—to immerse readers in a world of flux without forsaking verisimilitude. |

The novel turns on the case of the eponymous inheritance, a desk. But this is far from the typical desk. Namely, we are concerned with a bargueño, an ornate desk whose origins are traced to the Iberian Peninsula. It conjures images of a medieval bestiary or sixteenth-century chronicler at work—more museum piece than household object. If one were to ask how to write a detective story in an era of globalization, the first answer would certainly not be to begin with a bargueño, or any desk for that matter. Yet, Reyes-Ruiz uses it to plumb, with the eye of a New School-trained anthropologist, tropes of the detective genre and raise issues of the cultural and material underpinnings of today’s world. He employs crisp dialogue and brief chapters to ensure readers are all-in for the fast-paced investigation of The Inheritance’s far-flung locales.

What binds these places is the bargueño. Adriana inherits the desk after her grandfather passes away, and a fight over its provenance ensues, which eventually entangles a US law firm, the Colombian government, Japanese mafia, Spanish academia, and Big Money in the United Arab Emirates. When it was made, legal questions of its rightful owner, and its value are all part of the desk’s biography, as it were. And there is even a bit of sleuthing in the form of subtle linguistic clues uncovered by the likes of university professors. The histories and people that constellate around the DNA lineage of the bargueño’s maker paint the desk as the material element in a detective fiction of global scale for an age of genetic testing (think: 23andMe).

Without giving away too much of the plot, we can add that the bargueño’s origin story speaks to human migration flows and their painful past, present, and future. In other words, it is a search for origins that is geopolitical in nature. The desk simultaneously condenses Iberian plurality and the peninsula’s bloody battles, signaling the dangerous allure of narratives of purity. Establishing the value of the desk through genetic testing, however, cannot be separated from the threat of gender-based violence latent in the story’s development.

As mentioned earlier, Tony and Adriana are fleeing the yakuza because of an unpaid debt. This debt stems from Adriana’s decision to help a woman escape from a house used to confine “foreign hostesses” and “exotic dancers” who work in nightclubs run by the yakuza. Though neither Tony nor Adriana are explicitly painted as facilitating the sex trade, they are undoubtedly part of a network engaged in the migration of women from Eastern Europe or Latin America in a global labor circuit, which, as the novel recognizes, often entails modeling but also coerced sex work. In this way, The Inheritance is consonant with Verónica Gago’s critique of narratives of trafficking that only highlight migrants’ passivity.

The struggle to determine the origin of the bargueño speaks to the enmeshed nature of types of violence and how resisting gender-based violence cuts across multiple modalities of oppression. Thus, when the novel speaks to the leveraging of migration flows to escape poverty or analyzes converso iconography, it does so with an awareness of the warped structures of the world and contemporary economy.

On balance, the novel draws readers in with promises of international intrigue, and it does not disappoint. It unpacks the searches for origins while demanding critical reflection on the gendered modes of (forced) labor in terms of migration. The Inheritance proffers a literary response to the sedimentation of materiality and nefarious expansionist histories. Reading the novel is enriched by these multiple strands and in turn enriches ways of understanding the path dependency of the ills of our globalized world.

Rafael Reyes-Ruiz was born in Bogota, Colombia, holds a PhD in Anthropology from the New School for Social Research, and has taught at Oberlin College and Zayed University. Considered part of the #NewLatinoBoom, he publishes literary works in Spanish and English. His novels include: Las ruinas/The Ruins, La forma de las cosas/The Shape of Things, El samurái/The Samurai, and, most recently, La herencia/The Inheritance.

The Inheritance is a publication by Jade Publishing.

What binds these places is the bargueño. Adriana inherits the desk after her grandfather passes away, and a fight over its provenance ensues, which eventually entangles a US law firm, the Colombian government, Japanese mafia, Spanish academia, and Big Money in the United Arab Emirates. When it was made, legal questions of its rightful owner, and its value are all part of the desk’s biography, as it were. And there is even a bit of sleuthing in the form of subtle linguistic clues uncovered by the likes of university professors. The histories and people that constellate around the DNA lineage of the bargueño’s maker paint the desk as the material element in a detective fiction of global scale for an age of genetic testing (think: 23andMe).

Without giving away too much of the plot, we can add that the bargueño’s origin story speaks to human migration flows and their painful past, present, and future. In other words, it is a search for origins that is geopolitical in nature. The desk simultaneously condenses Iberian plurality and the peninsula’s bloody battles, signaling the dangerous allure of narratives of purity. Establishing the value of the desk through genetic testing, however, cannot be separated from the threat of gender-based violence latent in the story’s development.

As mentioned earlier, Tony and Adriana are fleeing the yakuza because of an unpaid debt. This debt stems from Adriana’s decision to help a woman escape from a house used to confine “foreign hostesses” and “exotic dancers” who work in nightclubs run by the yakuza. Though neither Tony nor Adriana are explicitly painted as facilitating the sex trade, they are undoubtedly part of a network engaged in the migration of women from Eastern Europe or Latin America in a global labor circuit, which, as the novel recognizes, often entails modeling but also coerced sex work. In this way, The Inheritance is consonant with Verónica Gago’s critique of narratives of trafficking that only highlight migrants’ passivity.

The struggle to determine the origin of the bargueño speaks to the enmeshed nature of types of violence and how resisting gender-based violence cuts across multiple modalities of oppression. Thus, when the novel speaks to the leveraging of migration flows to escape poverty or analyzes converso iconography, it does so with an awareness of the warped structures of the world and contemporary economy.

On balance, the novel draws readers in with promises of international intrigue, and it does not disappoint. It unpacks the searches for origins while demanding critical reflection on the gendered modes of (forced) labor in terms of migration. The Inheritance proffers a literary response to the sedimentation of materiality and nefarious expansionist histories. Reading the novel is enriched by these multiple strands and in turn enriches ways of understanding the path dependency of the ills of our globalized world.

Rafael Reyes-Ruiz was born in Bogota, Colombia, holds a PhD in Anthropology from the New School for Social Research, and has taught at Oberlin College and Zayed University. Considered part of the #NewLatinoBoom, he publishes literary works in Spanish and English. His novels include: Las ruinas/The Ruins, La forma de las cosas/The Shape of Things, El samurái/The Samurai, and, most recently, La herencia/The Inheritance.

The Inheritance is a publication by Jade Publishing.

Comment Box is loading comments...

|

|