Interview with Renee Goust

|

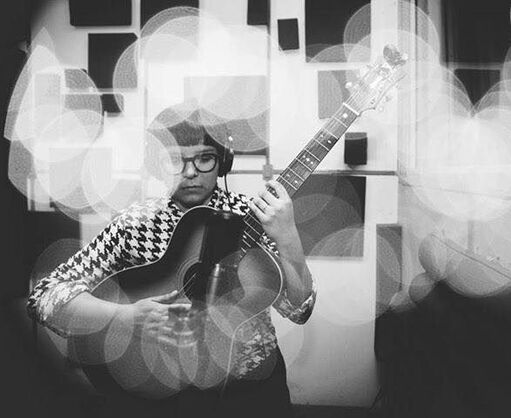

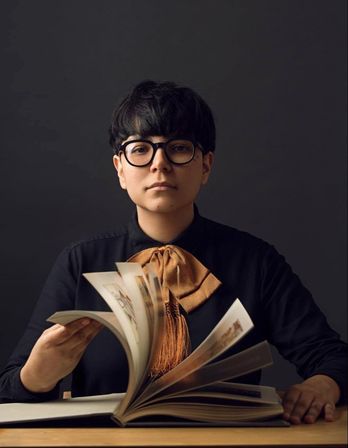

Renee Goust is a Brooklyn-based, bicultural singer and songwriter who has recently tackled social issues through her songs such as violence towards women as well as other social issues in the U.S. and Mexico. Her current single La Cumbia Feminazi has recently become a big hit on social media and is now available for pre-sale on iTunes in both acoustic and full band versions. GERALD PADILLA: Renee, thank you for being on Latino Book Review. RENEE GOUST: It’s a pleasure! Thanks a lot for having me, Gerald. |

PADILLA: You currently live in Brooklyn. Can you tell us about your bicultural experience? How long have you lived in Brooklyn and can you tell us a little about your Mexican roots?

GOUST: My parents are from the Northern Mexican state of Sonora, which shares a long border with Arizona. I was raised in a border town, so my bicultural experience pretty much dates back to the day I was born. Back then, before U.S. immigration policy was as strict as it is today, it was more common for pregnant Mexican women to cross into the United States a few days before they were due so their baby could have dual citizenship. I was lucky that my parents thought ahead. They wanted me to have the possibility of choosing whether to live in Mexico or in the States.

I was born in Tucson, Arizona and just two days later, when I was released from the hospital, I was brought home to Nogales, Sonora, which is just eighty miles south of Tucson. I was raised in what we call “Ambos Nogales”, which means “both Nogales” (Nogales, Sonora borders Nogales, Arizona). I spent the first seventeen years of my life there- crossing the border back and forth five days a week - going to private school in Nogales, Arizona every morning, then back home to Nogales, Sonora every afternoon. All my classes were in English, but at home we spoke Spanish. That made me bilingual and bicultural by default.

The High School I attended had the motto: “bilingual, bicultural, by choice”. Everyone I grew up around spoke English and Spanish equally well, so I never truly realized how special and particular this was, until I moved south to Guadalajara, Mexico to go to music school. My friends there called me “la gringa” or “la pocha” because I would pronounce certain words (such as “e-mail” or “hard rock”) with an American accent. The funny part is: now that I live in Brooklyn, I’m the “Mexican friend.”

I’ve lived in New York City for ten years. I’ve rented apartments in Manhattan, Queens, Jersey City and Brooklyn- I’ve been all over! I definitely feel like a New Yorker- I run around like one, I complain like one, I curse like one, but most importantly: I embrace diversity like one! I’m also very Mexican, though. I don’t celebrate Cinco de Mayo, I cried when Juan Gabriel died, I love grasshopper tacos. My Mexican friends don’t understand how I can love peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, my American friends think letting children eat pickled jalapenos is plain evil. I grew up eating both! That’s what being bicultural has meant to me: being Mexican and American at once, being half of each, and perhaps being neither fully. Only bicultural people can understand what that feels like. For me, it’s brought joy and confusion and pride and a lifetime search for a sense of belonging and true identity. Being bicultural means my answer to the question “Where are you from?” is longer than most peoples’.

PADILLA: How did your music journey begin? Is there a tradition of music in your family or is it something you started on your own?

GOUST: There’s a tradition of enjoying music in my family, but I’m definitely the first musician. My mom loves Top 40’s pop music and my dad loves older Mexican music in general. My brothers and I grew up listening to both these things at home. I remember dad would blast Los Panchos or Cuco Sanchez early on Sunday mornings! It was our alarm clock, it drove us crazy!

GOUST: My parents are from the Northern Mexican state of Sonora, which shares a long border with Arizona. I was raised in a border town, so my bicultural experience pretty much dates back to the day I was born. Back then, before U.S. immigration policy was as strict as it is today, it was more common for pregnant Mexican women to cross into the United States a few days before they were due so their baby could have dual citizenship. I was lucky that my parents thought ahead. They wanted me to have the possibility of choosing whether to live in Mexico or in the States.

I was born in Tucson, Arizona and just two days later, when I was released from the hospital, I was brought home to Nogales, Sonora, which is just eighty miles south of Tucson. I was raised in what we call “Ambos Nogales”, which means “both Nogales” (Nogales, Sonora borders Nogales, Arizona). I spent the first seventeen years of my life there- crossing the border back and forth five days a week - going to private school in Nogales, Arizona every morning, then back home to Nogales, Sonora every afternoon. All my classes were in English, but at home we spoke Spanish. That made me bilingual and bicultural by default.

The High School I attended had the motto: “bilingual, bicultural, by choice”. Everyone I grew up around spoke English and Spanish equally well, so I never truly realized how special and particular this was, until I moved south to Guadalajara, Mexico to go to music school. My friends there called me “la gringa” or “la pocha” because I would pronounce certain words (such as “e-mail” or “hard rock”) with an American accent. The funny part is: now that I live in Brooklyn, I’m the “Mexican friend.”

I’ve lived in New York City for ten years. I’ve rented apartments in Manhattan, Queens, Jersey City and Brooklyn- I’ve been all over! I definitely feel like a New Yorker- I run around like one, I complain like one, I curse like one, but most importantly: I embrace diversity like one! I’m also very Mexican, though. I don’t celebrate Cinco de Mayo, I cried when Juan Gabriel died, I love grasshopper tacos. My Mexican friends don’t understand how I can love peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, my American friends think letting children eat pickled jalapenos is plain evil. I grew up eating both! That’s what being bicultural has meant to me: being Mexican and American at once, being half of each, and perhaps being neither fully. Only bicultural people can understand what that feels like. For me, it’s brought joy and confusion and pride and a lifetime search for a sense of belonging and true identity. Being bicultural means my answer to the question “Where are you from?” is longer than most peoples’.

PADILLA: How did your music journey begin? Is there a tradition of music in your family or is it something you started on your own?

GOUST: There’s a tradition of enjoying music in my family, but I’m definitely the first musician. My mom loves Top 40’s pop music and my dad loves older Mexican music in general. My brothers and I grew up listening to both these things at home. I remember dad would blast Los Panchos or Cuco Sanchez early on Sunday mornings! It was our alarm clock, it drove us crazy!

|

My mother’s mom, who I grew up very close to, has always been a huge music fan and recently joined a local choir back home in Nogales. I often come to their rehearsals when I’m visiting. We share that passion and it really brings us together. She loves it when I come in and sing romantic oldies for them. I guess that’s as much of a music tradition as I can think of being in my family.

My journey as a musician began when I started piano lessons at 7 or 8 years old. I learned to read music and played simple pieces by Bach and Beethoven. I had a love-hate relationship with it but kept taking lessons because my parents had gone all the way and bought me an upright piano, which was an expense well out of their comfort zone. They bought it used from a friend whose daughter had grown up and wasn’t interested in piano anymore. The purchase included a piano teacher recommendation and so I just kind of rode the wave. |

I started writing little variations to my piano exercises and improvising on my own a few years later. Then eventually I wrote a couple love songs and wanted to play them for my friends in school, which made me realize that the piano isn’t a portable instrument and awakened my interest in learning to play guitar. I took a month-long primer course in Hermosillo, Mexico using a cheap Mexican acoustic “Paracho” guitar my dad had bought me. Learning a second instrument felt very natural to me because I already knew all the music theory. That got me really pumped, so I saved up my allowances and bought a guitar chord chart and taught myself my favorite pop-rock tunes. I remember the first song I ever learned to cover was Shakira’s “Pies Descalzos, Sueños Blancos” from her 1995 record “Pies Descalzos”. It’s funny to look back on it now, because that record came out more than twenty years ago, but I think it’s safe to say she’s the reason I decided to learn guitar. I first heard her music in summer camp 1996 - I must have been 9 years old- and I just fell in love with her lyrics. I started writing my little piano songs shortly thereafter. I remember getting in trouble when my mom found the lyrics to my song “I Hate School” inside my 6th grade notebook! I think I was trying to play the “cool rebel” kid to impress my friends, but in fact I was quite the class nerd.

During my last year in high school I decided I wanted to pursue music more seriously and went to the Universidad de Guadalajara for classical singing. I ended up not enjoying the rigidity of operatic technique and the competitive atmosphere in classical music in general, so I dropped out after my third year. My parents were pretty upset but decided to give me another chance under the condition that I choose a different career path. That’s when I moved to New York. I came here for cooking school but in reality, I had chosen the city strategically for its lively music scene and cultural diversity. I couldn’t be happier with my choice!

PADILLA: Your song La Cumbia Feminazi has received wide international attention for its powerful and relevant lyrics in response to today’s machismo and anti-feminism. What inspired you to write such passionate lyrics? Did the event occur the way you describe it in the song?

GOUST: There’s usually an element of fiction and an element of reality in my lyrics. I think that’s what makes songwriting such a compelling art form for me. I love that you can tell the whole gut-spilling truth about a situation and still have the luxury of adding a magical or dramatic touch to make it more memorable. I think Angel Olsen calls this “augmented reality”.

La Cumbia Feminazi is a chronicle of me being trolled by an unknown online macho! It’s certainly a memoir that was inspired by a particular incident (on Youtube, actually) but I wanted to broaden the scope of the song and take the opportunity to condemn machismo in general. I aimed to do so with the use of sarcasm, by changing voices between me and the aggressor in hopes of pointing out how ridiculous and distasteful the use of the word “Feminazi” is. The song went viral as soon as I uploaded it on Facebook. It got the wildest responses ranging from personal thank yous to people in Spain and Latin America writing to share their stories with me, to hurtful insults and rape threats on Twitter. The hate was a little scary, but in the end it only proved my point and further evidenced the terrible problem that is misogyny today.

I have self-identified as a feminist ever since I found out the actual meaning of the word, which is that feminism seeks equality of rights, opportunities and responsibilities between men and women. Where I come from, feminist is still a bad word and nobody wants to be associated with it. There’s a lot of misinformation around “the F word”. There’s a lot of hate towards it, which is funny because Northern Mexican women are regarded by the rest of the country as being super tough and dominant, but in reality we’re still expected to dress, think and act a certain way in order to be considered objects of desire. I had a teacher in high school who very proudly called herself a feminist, and she was widely criticized for it. Students perceived her as being a radical, when in reality she was a brave progressive thinker trying to enlighten her small town students. I keep in touch with her still. She was really proud of me for writing La Cumbia Feminazi.

PADILLA: In today’s music industry where there is a tendency for commercial music to be two-dimensional and superficial, how has the community responded to your bold, socially introspective, artistic initiative?

During my last year in high school I decided I wanted to pursue music more seriously and went to the Universidad de Guadalajara for classical singing. I ended up not enjoying the rigidity of operatic technique and the competitive atmosphere in classical music in general, so I dropped out after my third year. My parents were pretty upset but decided to give me another chance under the condition that I choose a different career path. That’s when I moved to New York. I came here for cooking school but in reality, I had chosen the city strategically for its lively music scene and cultural diversity. I couldn’t be happier with my choice!

PADILLA: Your song La Cumbia Feminazi has received wide international attention for its powerful and relevant lyrics in response to today’s machismo and anti-feminism. What inspired you to write such passionate lyrics? Did the event occur the way you describe it in the song?

GOUST: There’s usually an element of fiction and an element of reality in my lyrics. I think that’s what makes songwriting such a compelling art form for me. I love that you can tell the whole gut-spilling truth about a situation and still have the luxury of adding a magical or dramatic touch to make it more memorable. I think Angel Olsen calls this “augmented reality”.

La Cumbia Feminazi is a chronicle of me being trolled by an unknown online macho! It’s certainly a memoir that was inspired by a particular incident (on Youtube, actually) but I wanted to broaden the scope of the song and take the opportunity to condemn machismo in general. I aimed to do so with the use of sarcasm, by changing voices between me and the aggressor in hopes of pointing out how ridiculous and distasteful the use of the word “Feminazi” is. The song went viral as soon as I uploaded it on Facebook. It got the wildest responses ranging from personal thank yous to people in Spain and Latin America writing to share their stories with me, to hurtful insults and rape threats on Twitter. The hate was a little scary, but in the end it only proved my point and further evidenced the terrible problem that is misogyny today.

I have self-identified as a feminist ever since I found out the actual meaning of the word, which is that feminism seeks equality of rights, opportunities and responsibilities between men and women. Where I come from, feminist is still a bad word and nobody wants to be associated with it. There’s a lot of misinformation around “the F word”. There’s a lot of hate towards it, which is funny because Northern Mexican women are regarded by the rest of the country as being super tough and dominant, but in reality we’re still expected to dress, think and act a certain way in order to be considered objects of desire. I had a teacher in high school who very proudly called herself a feminist, and she was widely criticized for it. Students perceived her as being a radical, when in reality she was a brave progressive thinker trying to enlighten her small town students. I keep in touch with her still. She was really proud of me for writing La Cumbia Feminazi.

PADILLA: In today’s music industry where there is a tendency for commercial music to be two-dimensional and superficial, how has the community responded to your bold, socially introspective, artistic initiative?

|

GOUST: I’ve certainly lost more than a couple friendships since writing La Cumbia Feminazi. People expect you to just write love songs and be satisfied, or to be cute and quirky and hipstery and call it a day. Some musicians want to appeal to the broadest market possible and achieve commercial success at all costs. While that is a respectable choice, I feel like it’s such a waste to have a special talent and use it to put forth the same trite old messages.

Cass McCombs has a really great song called “Bum, Bum, Bum” which critiques the breeding of white supremacy. In this song he says “And white bread artists won’t even look at you when they know it’s true, what you gonna do?” I have certainly felt this way since writing La Cumbia Feminazi. The parameters of what’s acceptable or cool or edgy when writing a protest song include criticizing the government or addressing the unfair distribution of wealth, maybe. But as soon as you touch on feminism or LGBTQIA issues, it becomes a problem and people aren’t afraid to be vocal about it. |

I was very lucky to be a sit-in guest in my wife’s PhD-level class about gender and otherness a couple years ago, and it completely changed my life. La Cumbia Feminazi is definitely a result of that newly-gained feminist theory knowledge and hyper-awareness of gender inequality in our times. I used to write a lot of sad music. I struggled with depression for many years and songwriting had always been my catharsis. I think people who knew my music from way back learned to expect that darkness, so it’s natural that they were confused when all of a sudden I released this feminist tune that showed me as an empowered woman and no longer a helpless girl. It was definitely an uncomfortable artistic transition for me, but part of my duty to myself as an artist and as a person is to never stop growing and challenging myself. I feel like more of a grown-up now and I want to be singing about things that happen on the outside as well as on the inside.

PADILLA: Socially speaking, we are living in a very difficult time in many aspects. Do you think these times will create or are creating more artists like you who are willing to stand up for socially relevant issues?

GOUST: Absolutely. I think the advent of social media and the internet in general make information travel faster and bring us closer to places in the world we would have never been able to see before. Syria comes to mind immediately. There’s a lot to be said about hard times bringing positive change. Think of the flower children, for example. The late 60’s and early 70’s were a time of massive evolution in social thinking and women’s rights and human rights in general. All of this amidst a terrible Nixon presidency and the last years of the Vietnam War, or as the Vietnamese call it the “Resistance War Against America”.

I do believe hard times tend to shake us up and make us more aware and vigilant. Artists are intelligent free thinkers. We’re influenced by the times. We’re part of a society and when that society is under attack, I think as creative creatures we’re particularly vulnerable to those changes. I personally feed off of the vibes that surround me a lot for my writing. When freedom of speech is threatened, it’s a direct threat to my existence and it only makes me want to fight back stronger, speak up louder. I’ve noticed it on the big galas such as the Grammys this year. A Tribe Called Quest had an amazing protest performance against the current administration. Katy Perry also put forth her “Resist” message. Lots of actors and visual artists have been doing the same. We are standing up and will continue to stand up against the oppressive patriarchal status quo of our times. Our future depends on it.

PADILLA: In your song, Tratado de Paz, you say, “Hagamos un tratado de paz. Yo te prometo ya no hablar de más. Deshazte del chaleco anti-balas. Ya tienes quien te cuide la espalda.” Can you tell us about the background and context of these lyrics? Is there a specific event that led to this song?

GOUST: Tratado de Paz is a very personal song and a very global one at once. It’s about making up after an argument with my loved one, but it’s also about world peace and more specifically peace on the streets. I wrote it to help me heal after a heated discussion, and in the process of writing it I came to the realization that peace is a very fragile thing that must be taken care of at all times or else it slips away easily.

PADILLA: Socially speaking, we are living in a very difficult time in many aspects. Do you think these times will create or are creating more artists like you who are willing to stand up for socially relevant issues?

GOUST: Absolutely. I think the advent of social media and the internet in general make information travel faster and bring us closer to places in the world we would have never been able to see before. Syria comes to mind immediately. There’s a lot to be said about hard times bringing positive change. Think of the flower children, for example. The late 60’s and early 70’s were a time of massive evolution in social thinking and women’s rights and human rights in general. All of this amidst a terrible Nixon presidency and the last years of the Vietnam War, or as the Vietnamese call it the “Resistance War Against America”.

I do believe hard times tend to shake us up and make us more aware and vigilant. Artists are intelligent free thinkers. We’re influenced by the times. We’re part of a society and when that society is under attack, I think as creative creatures we’re particularly vulnerable to those changes. I personally feed off of the vibes that surround me a lot for my writing. When freedom of speech is threatened, it’s a direct threat to my existence and it only makes me want to fight back stronger, speak up louder. I’ve noticed it on the big galas such as the Grammys this year. A Tribe Called Quest had an amazing protest performance against the current administration. Katy Perry also put forth her “Resist” message. Lots of actors and visual artists have been doing the same. We are standing up and will continue to stand up against the oppressive patriarchal status quo of our times. Our future depends on it.

PADILLA: In your song, Tratado de Paz, you say, “Hagamos un tratado de paz. Yo te prometo ya no hablar de más. Deshazte del chaleco anti-balas. Ya tienes quien te cuide la espalda.” Can you tell us about the background and context of these lyrics? Is there a specific event that led to this song?

GOUST: Tratado de Paz is a very personal song and a very global one at once. It’s about making up after an argument with my loved one, but it’s also about world peace and more specifically peace on the streets. I wrote it to help me heal after a heated discussion, and in the process of writing it I came to the realization that peace is a very fragile thing that must be taken care of at all times or else it slips away easily.

|

A long time ago I read a phrase somewhere that said that fear, not hate, is love’s worst enemy. I thought of this as I wrote my song and resolved my feelings. I thought of how the world’s major problems stem from the fact that our countries’ leaders very often act out of fear, spite, ego, and hate, but very rarely out of love. As I wrote down some lyrics ideas, I realized that the only way to ever achieve peace is to start from within, at the micro level. It’s silly to criticize wars and bombings and then turn around and pick a fight with your neighbor or your lover.

Tratado de Paz is a proposal from me to my partner to sign a peace treaty where the clauses are: I’ll watch my missile mouth and you’ll take off your bulletproof vest and we’ll have each others’ backs. I come from a town that became notorious for its drug-trafficking-related violence in the past couple of decades, so the bulletproof vest metaphor came to me very naturally. PADILLA: In your song, El Patriota Suicida, you speak of a Mexican patriot who wants to commit suicide. Is this a reflection of the violence occurring in Mexico and other countries in Latin America or does it reflect the longing of your homeland? |

GOUST: El Patriota Suicida is the oldest song I’ve written that’s still in rotation. I wrote it in 2007 during a particularly dark period in my life, just two or three months after dropping out of college. I had no idea where I was headed. I was far from home, alone, and feeling quite anxious and disappointed in myself. I remember writing it while sitting on a twin bed in my tiny studio apartment where there was only enough room for the bed, a mini fridge and a desk. My life had changed so quickly and I was now on this new path that I wasn’t very excited about but I also knew I had a chance to save myself.

I was feeling very homesick. I remember thinking: “Wow! I feel so depressed right now, but what about the people who don’t have a chance to go back home and visit? What kind of thoughts go through their heads in times of longing? Is there hope for them? I would probably kill myself.” So I started jotting down some lines on a little composition book. I was on the fifth floor of a walk-up, and there was an open window with a small white curtain waving in the wind. The sky was dense with dark clouds. It was very dramatic. So I just imagined that I was an immigrant who was stuck in this faraway country, had lost all hope and was ready to finish it. And to my surprise, a couple hours later El Patriota Suicida was born! I ended up liking the song a lot, which cheered me up.

PADILLA: Can you tell us about your upcoming concerts and projects?

GOUST: Yes! I’m really excited that La Cumbia Feminazi is now available for pre-order on iTunes! The single will be on all major streaming services as well as on my Youtube, Bandcamp, and Soundcloud pages starting June 23rd. It will include the full band version and the acoustic (guitar and vocals) version of the song. I’ll be playing a single release show at Piano’s in Manhattan on June 24th to celebrate.

My full EP “Septiembre”, which includes La Cumbia Feminazi, Tratado de Paz, El Patriota Suicida, and two never-before-released songs in Spanish is coming out on my birthday, September 1st. I’ll be playing an EP Release show at Rockwood Music Hall Stage 2 in Manhattan on September 8th at 7 pm to promote it. I’m also scheduling some shows in the Northeastern US, and I’ll be touring major cities in Mexico during the second part of September to spread the word about the record. I have music in English coming out in 2018 but it’s too soon to spill the beans!

PADILLA: Renee, thank you once more for being with us. It was a pleasure to have you on Latino Book Review. We wish you the best and hope to hear more of your music.

GOUST: Thanks again for having me, Gerald, and for the amazing work you do at Latin Book Review.

I was feeling very homesick. I remember thinking: “Wow! I feel so depressed right now, but what about the people who don’t have a chance to go back home and visit? What kind of thoughts go through their heads in times of longing? Is there hope for them? I would probably kill myself.” So I started jotting down some lines on a little composition book. I was on the fifth floor of a walk-up, and there was an open window with a small white curtain waving in the wind. The sky was dense with dark clouds. It was very dramatic. So I just imagined that I was an immigrant who was stuck in this faraway country, had lost all hope and was ready to finish it. And to my surprise, a couple hours later El Patriota Suicida was born! I ended up liking the song a lot, which cheered me up.

PADILLA: Can you tell us about your upcoming concerts and projects?

GOUST: Yes! I’m really excited that La Cumbia Feminazi is now available for pre-order on iTunes! The single will be on all major streaming services as well as on my Youtube, Bandcamp, and Soundcloud pages starting June 23rd. It will include the full band version and the acoustic (guitar and vocals) version of the song. I’ll be playing a single release show at Piano’s in Manhattan on June 24th to celebrate.

My full EP “Septiembre”, which includes La Cumbia Feminazi, Tratado de Paz, El Patriota Suicida, and two never-before-released songs in Spanish is coming out on my birthday, September 1st. I’ll be playing an EP Release show at Rockwood Music Hall Stage 2 in Manhattan on September 8th at 7 pm to promote it. I’m also scheduling some shows in the Northeastern US, and I’ll be touring major cities in Mexico during the second part of September to spread the word about the record. I have music in English coming out in 2018 but it’s too soon to spill the beans!

PADILLA: Renee, thank you once more for being with us. It was a pleasure to have you on Latino Book Review. We wish you the best and hope to hear more of your music.

GOUST: Thanks again for having me, Gerald, and for the amazing work you do at Latin Book Review.

|

5/28/2017

Comment Box is loading comments...

|

|