Poemas en blanco y negro

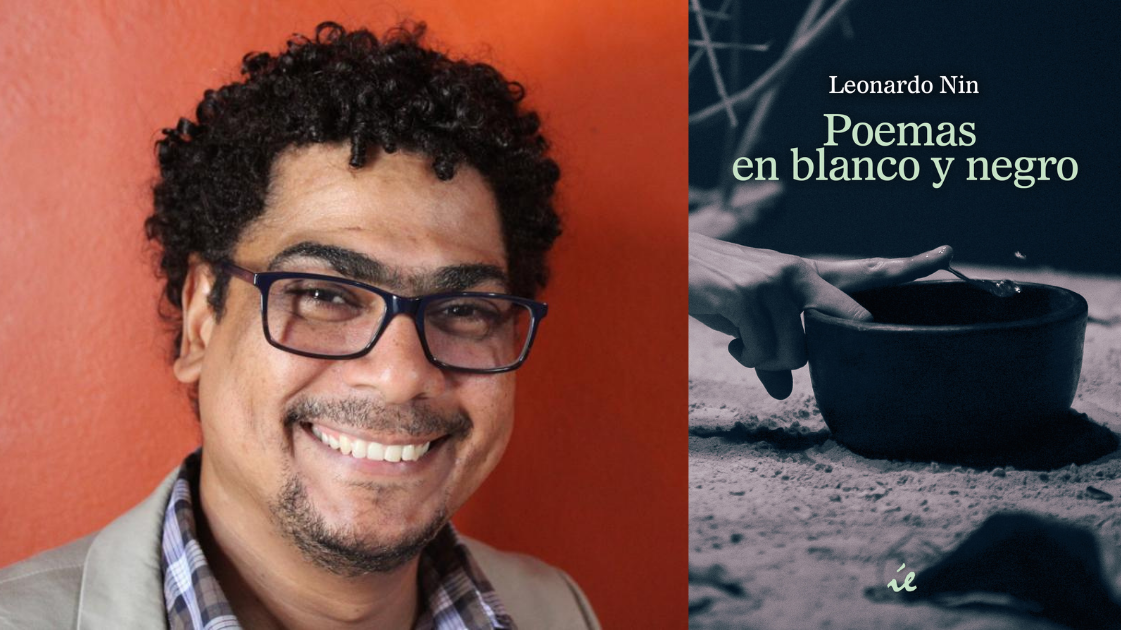

Leonardo Nin

|

Poemas en blanco y negro, by Dominican writer Leonardo Nin, has been republished this past November by Índole Editores, from El Salvador. Its release is a new opportunity to have a singular poetic experience, in which opposites confront and fight, but also mix and intertwine, and show us unexpected lights and shadows, shadows and lights, of life. The collection is structured in three sections: “Poemas en blanco” (“Poems in white”), “Poemas en negro” (“Poems in black”) and “En gris y cal” (“In grey and lime”), which explore from different perspectives a wide range of themes, such as existential reflection, social and political denunciation, otherness, and Afro-Caribbean identity. If there is a word that could define this book, it is “subversive.” According to the Diccionario de la Real Academia Española, “subvert” is “To disrupt something or make it cease to have the normal or characteristic order ...”. That is exactly what happens throughout these pages. The subversion starts from the very title of the first poem, “Addendum,” since an addendum is a “set of additions at the end of a piece of writing.” The addendum states, “Este poema es.../ epitafio efímero…/ falible introspección…/ anexo impropio/ a un testamento sepultado al azar” (“This poem is.../ an ephemeral epitaph.../ a fallible introspection.../ an improper annex/ to a testament buried at random”) (11-12). In the world of this book, there is nothing definitive, nothing firm in the course of prolonged time (we must remember that, for example, an epitaph is a text written to last); what we find is change and a constant reminder of the evolution of things. The poet himself acknowledges his transience: “Si mi mano fuera de tinta/ tatuaría mi historia en la pared del olvido” (“If my hand were made of ink/ I would tattoo my story on the wall of oblivion”) (11). |

Existential reflection, as mentioned, plays a fundamental role in this book, especially the reflection on one’s own identity: what and who we are. Perhaps, the poem that goes most deeply into these questions is “Bios. La muerte de un Narciso” (“Bios. The death of a Narcissus”). In the poem, Nin makes his own version of the Greek myth of Narcissus. In the myth, Narcissus falls in love with his own image reflected in a pond. Here, the author gathers several idioms and creates a collage, a water of ripples, to give us an image of himself (this play of words is not entirely translatable): “Tengo boca de estómago,/ ojo de ciclón, brazo de mar,/ …pie de la letra,/ dientes de ajo,/ …beso de Judas,/ paso de tiempo,/ piel de gallina,/ cuerpo del delito” (20). And also, in the Greek myth, Narcissus drowns in the pond; in the poem, the author closes by giving us an empty pond: “nuevamente me transformo en lo que realmente soy/ y siempre he sido:/ Nada y nada más que nada” (“Once again, I become what I really am/ and always have been:/ Nothing and nothing more than nothing”) (21).

Criticism of the capitalist system also occupies an important place in these verses. “Soy energúmeno,/ consumidor empedernido de sandeces/ …uno más del enjambre cabizbajo de langostas grises” (“I am a lunatic,/ hardened consumer of nonsense/ ...one more of the downcast swarm of gray locusts”) (30). But in spite of living and writing in this oppressive and individuality-destroying system, the poet doesn’t give up hope: “Pero ayer, entre copas honestas/ mi mejor amiga me llamó/ utópicamente absurdo” (“But yesterday, between honest drinks/ my best friend called me/ utopianly absurd”), he says in the poem “Utopiocracia” (“Utopiocracy”) (41).

Also, the historical memory and the social and political denunciation of his native land are strikes us in verses such as: “Mi isla no es más que un punto en letargo,/ una fosa de memorias” (“My island is nothing more than a dot in lethargy,/ a mass grave of memories”) (39) and “El problema con los desaparecidos/ son las sepulturas sin uso/ …encontrar adónde llevar flores” (“The problem with the disappeared/ are the unused graves/ ...finding where to take flowers”) (28).

And inseparably linked to the Dominican Republic is the Afro-Caribbean identity. In “Si Haití fuera blanco” (“If Haiti was white”) the poet points out that there are “mitos sembrados en el otro inventado” (“myths sown in the invented other”) (61); in “Te deum,” the character closes by saying “Yo tuve, sé que tuve./ Pero ayer,/ entre leyes y prejuicios/ me lo arrebató la historia…” (“I had, I know I had./ But yesterday,/ between laws and prejudices/ history took it away from my hands...”) (69); and in “Levitando” (“Levitating”), the author says about his grandmother (who, he mentions in the dedication, recited him décimas, a traditional Spanish poetic form alive in the Caribbean, before going to sleep): “mi cuerpo [es] una barca flotando agradecida en el recuerdo/ de sus lágrimas” (“my body [is] a boat floating gratefully in the memory/ of her tears”) (40).

Leonardo Nin’s Poemas en blanco y negro shake reality as we know it, and makes us look at the other: the other human beings and the other realities. With these poems, whose words help us push aside the lies and dead words surrounding us, we might discover that the one who “dwells in the margins,” the one who exists “in the extremes,” the stranger who looks at us with the “eyes of the universe” is not as otherly or unknown or strange as we think. We can discover that he and she and all of them are ourselves.

Leonardo Nin is a Dominican writer based in Boston with a degree in anthropology from Harvard University. His publications include the short story collection Guazábaras and Sacrilegios del excomulgado (Sacrileges of the excommunicated); the poetry collections Espacio pagado (Paid space) and Poemas en blanco y negro (Poems in black and white); and the novels Sólo sé que le llamaban Sombra (I only know they called her Shadow) and Mañana, si Dios muere (Tomorrow, if God dies). He has won the literary prize Letras de Ultramar in theater, short story and novel. His literary work and essays on linguistic and anthropological research have been published in anthologies and journals in the United States, Latin America and Europe.

Poemas en blanco y negro is a publication by Índole Editores. Click to contact the press here.

Criticism of the capitalist system also occupies an important place in these verses. “Soy energúmeno,/ consumidor empedernido de sandeces/ …uno más del enjambre cabizbajo de langostas grises” (“I am a lunatic,/ hardened consumer of nonsense/ ...one more of the downcast swarm of gray locusts”) (30). But in spite of living and writing in this oppressive and individuality-destroying system, the poet doesn’t give up hope: “Pero ayer, entre copas honestas/ mi mejor amiga me llamó/ utópicamente absurdo” (“But yesterday, between honest drinks/ my best friend called me/ utopianly absurd”), he says in the poem “Utopiocracia” (“Utopiocracy”) (41).

Also, the historical memory and the social and political denunciation of his native land are strikes us in verses such as: “Mi isla no es más que un punto en letargo,/ una fosa de memorias” (“My island is nothing more than a dot in lethargy,/ a mass grave of memories”) (39) and “El problema con los desaparecidos/ son las sepulturas sin uso/ …encontrar adónde llevar flores” (“The problem with the disappeared/ are the unused graves/ ...finding where to take flowers”) (28).

And inseparably linked to the Dominican Republic is the Afro-Caribbean identity. In “Si Haití fuera blanco” (“If Haiti was white”) the poet points out that there are “mitos sembrados en el otro inventado” (“myths sown in the invented other”) (61); in “Te deum,” the character closes by saying “Yo tuve, sé que tuve./ Pero ayer,/ entre leyes y prejuicios/ me lo arrebató la historia…” (“I had, I know I had./ But yesterday,/ between laws and prejudices/ history took it away from my hands...”) (69); and in “Levitando” (“Levitating”), the author says about his grandmother (who, he mentions in the dedication, recited him décimas, a traditional Spanish poetic form alive in the Caribbean, before going to sleep): “mi cuerpo [es] una barca flotando agradecida en el recuerdo/ de sus lágrimas” (“my body [is] a boat floating gratefully in the memory/ of her tears”) (40).

Leonardo Nin’s Poemas en blanco y negro shake reality as we know it, and makes us look at the other: the other human beings and the other realities. With these poems, whose words help us push aside the lies and dead words surrounding us, we might discover that the one who “dwells in the margins,” the one who exists “in the extremes,” the stranger who looks at us with the “eyes of the universe” is not as otherly or unknown or strange as we think. We can discover that he and she and all of them are ourselves.

Leonardo Nin is a Dominican writer based in Boston with a degree in anthropology from Harvard University. His publications include the short story collection Guazábaras and Sacrilegios del excomulgado (Sacrileges of the excommunicated); the poetry collections Espacio pagado (Paid space) and Poemas en blanco y negro (Poems in black and white); and the novels Sólo sé que le llamaban Sombra (I only know they called her Shadow) and Mañana, si Dios muere (Tomorrow, if God dies). He has won the literary prize Letras de Ultramar in theater, short story and novel. His literary work and essays on linguistic and anthropological research have been published in anthologies and journals in the United States, Latin America and Europe.

Poemas en blanco y negro is a publication by Índole Editores. Click to contact the press here.

Comment Box is loading comments...

|

|