Liberato Kani: Pushing Quechua into the Mainstream

Ricardo Flores, who goes by the stage name Liberato Kani, is a rapper and songwriter from Peru who is revolutionizing hip-hop, not only in his home country, but around the world with his bilingual Spanish and Quechua music. Quechua was the lingua franca of the Inca Empire and has been spoken in the Andes for thousands of years, but despite having 8 million native speakers across Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, it has taken on the role of a second-class language since the arrival of Spanish in the region. The same is true of those who speak it; anti-Indigenous racism is pervasive throughout Latin America, and in many places speaking Quechua continues to be something that people are made to feel ashamed of. In recent years, however, urban Quechua (and Kichwa, as the language and ethnicity is known in Ecuador) artists such as Renata Flores, Los Nin, MafiAndina, and now Liberato, are building a movement to introduce Quechua to the mainstream music scene while simultaneously empowering Indigenous communities across the Andes. The name Liberato Kani, which means "I am free" or alternatively "I am a lover of freedom" in Quechua, was adopted by the artist in 2016 while recording his song "Kaykunapi." In a virtual interview with my Elementary Quechua class last month, he explained that his name was inspired by the way he feels while making music: "I felt that freedom with hip hop. It gave me a voice to express what I was feeling."

|

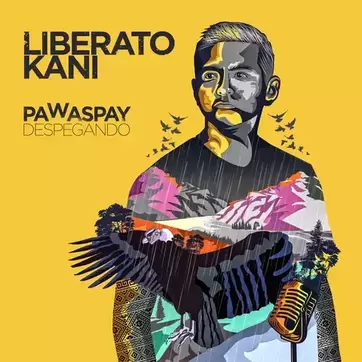

Liberato spoke with our class following the release of his new album "Pawaspay," which translates to "taking off" in Quechua. In 2018 he went on a tour by the same name in Spain, Cuba, Chile, and the U.S., marking the international success of his music. Alternating between Spanish and Quechua, Flores told us that this album is "a dream come true" for him. Like our conversation, Liberato’s album is bilingual, and he stressed the point that language is inherently political for Indigenous communities. Many people from Andean communities speak Spanish with a Quechua accent, which can automatically mark them for ridicule and criticism in primarily non-Indigenous settings. Liberato Kani has been quoted saying, "I speak Spanish badly because Quechua is my language,” which he says is a message of resistance against the stigma associated with Andean Spanish and a validation of the ways that Quechua has influenced Spanish.

|

Liberato recognizes how important his work is in creating positive representation for Indigenous kids and in making them take pride in their cultural identity. He hopes to see more Quechua and Kichwa artists enter the music scene, including Indigenous artists in the large Quechua diaspora, saying that "The more Quechua music there is, the more space we will take up in popular culture." To him, music has the potential to move culture anywhere in the world; Flores believes that even if people don't understand the lyrics to a song in a foreign language, they can understand its emotion, and hopefully that emotion is strong enough to make them want to learn more.

We spent much of our interview discussing "Pawaspay," which has ten hip-hop tracks that blend urban beats, themes of Indigenous pride, and Quechua and Spanish lyricism in a truly remarkable way. In the week leading up to the interview, my class spent some time going over his songs and translating their lyrics, and we were shocked by the fluidity that Quechua has in its expression of phrases and ideas that can be very difficult to translate into Spanish or English. When we mentioned this to Flores, he responded that "Quechua has its own way of expressing things, its own cosmovision...expressing things in Quechua is much different than expressing things in another language." Even if listeners are unable to understand the poetics of Flores' lyrics, their boldness paired with the dizzying speed he raps at on some tracks is unmistakably powerful.

Liberato, who lives in Lima, did not grow up speaking Quechua fluently, but instead began to learn it casually when he was eight years old while living with his grandmother in Apurimac, which is in the Peruvian highlands. This story may be familiar to many who are learning Quechua; it is, as with many Indigenous languages, an exercise in reconnecting with a language, a culture, and a history. For those who did not grow up speaking Quechua because their parents or grandparents were forced to abandon it in a Spanish-dominated society, or because they themselves chose to "forget" a language that Hispanic society does not value, relearning Quechua is an emotional process that centers identity and cultural responsibility to uplift the language. Liberato is still learning more everyday about how to write his lyrics in Quechua and says that one day he hopes to exclude Spanish from his music entirely, a goal that aligns with the bigger picture of his work. "I want Quechua to be a part of everyday life for everyone, everywhere in Peru,” he told us, and though he knows that there's a long road ahead to making that a reality, he's excited to be part of the growing movement of Quechua artists and youth pushing the language into all aspects of mainstream Latin American culture. For anyone interested in supporting Flores' efforts and learning about the incredible beauty of Quechua, "Pawaspay" is a great place to start.

We spent much of our interview discussing "Pawaspay," which has ten hip-hop tracks that blend urban beats, themes of Indigenous pride, and Quechua and Spanish lyricism in a truly remarkable way. In the week leading up to the interview, my class spent some time going over his songs and translating their lyrics, and we were shocked by the fluidity that Quechua has in its expression of phrases and ideas that can be very difficult to translate into Spanish or English. When we mentioned this to Flores, he responded that "Quechua has its own way of expressing things, its own cosmovision...expressing things in Quechua is much different than expressing things in another language." Even if listeners are unable to understand the poetics of Flores' lyrics, their boldness paired with the dizzying speed he raps at on some tracks is unmistakably powerful.

Liberato, who lives in Lima, did not grow up speaking Quechua fluently, but instead began to learn it casually when he was eight years old while living with his grandmother in Apurimac, which is in the Peruvian highlands. This story may be familiar to many who are learning Quechua; it is, as with many Indigenous languages, an exercise in reconnecting with a language, a culture, and a history. For those who did not grow up speaking Quechua because their parents or grandparents were forced to abandon it in a Spanish-dominated society, or because they themselves chose to "forget" a language that Hispanic society does not value, relearning Quechua is an emotional process that centers identity and cultural responsibility to uplift the language. Liberato is still learning more everyday about how to write his lyrics in Quechua and says that one day he hopes to exclude Spanish from his music entirely, a goal that aligns with the bigger picture of his work. "I want Quechua to be a part of everyday life for everyone, everywhere in Peru,” he told us, and though he knows that there's a long road ahead to making that a reality, he's excited to be part of the growing movement of Quechua artists and youth pushing the language into all aspects of mainstream Latin American culture. For anyone interested in supporting Flores' efforts and learning about the incredible beauty of Quechua, "Pawaspay" is a great place to start.

|

Comment Box is loading comments...

|

|