Interview With Maria Hinojosa

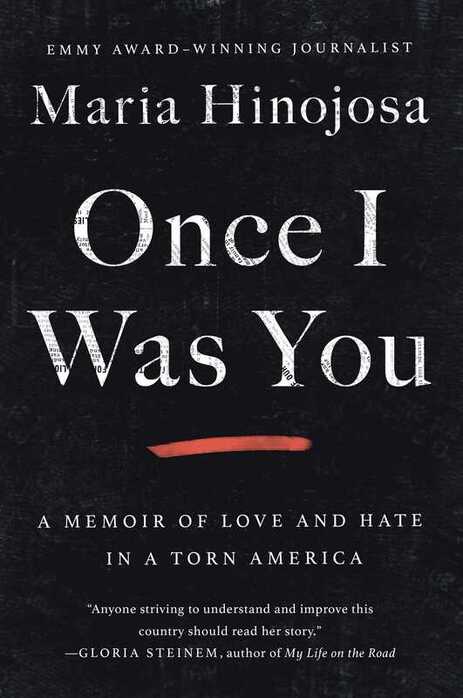

HECTOR “VALE” RENDÓN: Maria Hinojosa has been a journalist for nearly 30 years. She has won multiple awards, including four Emmys and two Kennedy Awards For Excellence in Journalism. She’s the host of the radio show, Latino USA, distributed by NPR, and she is the founder of Futuro Media, a nonprofit company focused on telling the stories of minorities in the U.S. She’s here with us to talk about her book, Once I Was You. Maria, thank you so much for being with us.

MARIA HINOJOSA: It’s my pleasure. Thank you so much for having me.

RENDÓN: I wanted to ask you about this new book that was published very recently, Once I Was You. Of course, it’s a memoir, and it talks about your experience in the U.S. But I wanted to ask you about why you decided to write this memoir. Tell us about your experience.

MARIA HINOJOSA: It’s my pleasure. Thank you so much for having me.

RENDÓN: I wanted to ask you about this new book that was published very recently, Once I Was You. Of course, it’s a memoir, and it talks about your experience in the U.S. But I wanted to ask you about why you decided to write this memoir. Tell us about your experience.

|

HINOJOSA: Well, actually, I was thinking of writing a much smaller book. The book that I thought I was going to write was going to be a small pocketbook called Illegal Is Not a Noun, as people use the term illegal to refer to a human being. The truth is that writing a book is a lot of emotional work. It’s a lot of physical labor. And I was prepared to write a little book. But it turned out that the publishing world didn’t want a little book from me. They wanted a bigger book. They wanted a big book. And so it turned out that it wasn’t just going to be a memoir. We really decided that this was going to be like a history book—a book that was going to be deeply intimate, deeply personal, and at the same time, a book that is telling the history of the United States through my eyes, through my experience. Physically and as an investigative journalist, I’d like to say that Gloria Steinem kind of got it best when she said, “It’s multiple books in one,” because it’s a book about being an immigrant, it’s a book about being a Mexican, it’s a book about being a Latina, it’s a book about being a journalist, it’s a book about being a survivor of rape. It’s a book about growing up in the civil rights era in the United States. And ultimately, it’s a triumphant book because I end up creating my own media company. When I knew that my book was going to be coming out in the fall of 2020, te lo juro de que I was just like, oh, gosh, by then nobody’s going to have anything new to say, about anything. And actually, the opposite is true. A lot of people feel like it was written for this moment and that it needs to be read in this moment. I think it even applies more than when it was published—because in this moment, at the end of 2020, I think there is expectation, there is possibility, there’s reckoning, but there’s also expectation and hope. In many ways, it feels fit for the end of the year.

|

When you purchase a book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission and so do independent book stores.

|

RENDÓN: It is very fit. And I think the current context actually relates very much to many of the stories that you tell in your book. You mentioned already that you are a survivor, and of course, many other things that have shaped your identity and who you are as an individual. When you say Once I Was You, who are you talking to? Who is “you” in this case?

HINOJOSA: Well, there are many authors who write a book, and they know what the title is, and they’re very lucky. I was writing this book, but I did not know what the title was. And we were very frustrated. I was very scared, honestly, because I was like, “Oh, my God”. My editor said, “Don’t worry, we’ll find a title, it will happen.” We were having such a hard time that we brought a new perspective, and somebody who hadn’t read the book. The introduction to the book is a moment where I encounter a little girl who is in the process of being trafficked, transported by individuals who were ultimately paid for by the U.S. government. And she was with a group of other children. They were being taken from McAllen to who knows where. We were on a flight to Houston. And I end that introductory moment, as I described this, witnessing the greatest horror of the United States of America—the separating of children, the taking of children as a form of punishment, and I was witnessing it in the airport. They denied me the capacity to speak to the children. They told me, “You’re not allowed, they’re not allowed to speak to anybody.” And so en voz alta, I just started saying loudly to the kids, “Hey,” in Spanish, “You have the right to speak to a journalist, you have the right to know that there are people here in this country who care about you and who want to know that you’re okay.” And then I looked to the little girl, and I wrote, “I wanted you to hear that I was saying all of this. I wanted you to know that I saw you because once I was you.” And in the writing of the book, it was revealed in great clarity to me that when I arrived in this country, with privilege, with a green card, with my mother and my family at the airport in Dallas in the year 1962, they almost took me. They almost took me from my mother’s arms. And in that sense, Once I Was You is that I was a child who was almost taken. I’m not in any way, shape or form saying I am a refugee from Central America. But there is something in my soul that can identify with the trauma of separation. It goes very deep, and I wasn’t separated because my mother empezó a gritar. You know, she just made a scene. She used her privilege. I thought it was just because she had a big mouth. But no, it was actually later that she told me, “That was my trauma speaking.” But you know, also in many ways, Once I Was You is kind of the way I work as a journalist. I really try to meet people where they are and to find myself in the people most unlike me. And in that sense, Once I Was You is just a broader statement that we share a common humanity.

HINOJOSA: Well, there are many authors who write a book, and they know what the title is, and they’re very lucky. I was writing this book, but I did not know what the title was. And we were very frustrated. I was very scared, honestly, because I was like, “Oh, my God”. My editor said, “Don’t worry, we’ll find a title, it will happen.” We were having such a hard time that we brought a new perspective, and somebody who hadn’t read the book. The introduction to the book is a moment where I encounter a little girl who is in the process of being trafficked, transported by individuals who were ultimately paid for by the U.S. government. And she was with a group of other children. They were being taken from McAllen to who knows where. We were on a flight to Houston. And I end that introductory moment, as I described this, witnessing the greatest horror of the United States of America—the separating of children, the taking of children as a form of punishment, and I was witnessing it in the airport. They denied me the capacity to speak to the children. They told me, “You’re not allowed, they’re not allowed to speak to anybody.” And so en voz alta, I just started saying loudly to the kids, “Hey,” in Spanish, “You have the right to speak to a journalist, you have the right to know that there are people here in this country who care about you and who want to know that you’re okay.” And then I looked to the little girl, and I wrote, “I wanted you to hear that I was saying all of this. I wanted you to know that I saw you because once I was you.” And in the writing of the book, it was revealed in great clarity to me that when I arrived in this country, with privilege, with a green card, with my mother and my family at the airport in Dallas in the year 1962, they almost took me. They almost took me from my mother’s arms. And in that sense, Once I Was You is that I was a child who was almost taken. I’m not in any way, shape or form saying I am a refugee from Central America. But there is something in my soul that can identify with the trauma of separation. It goes very deep, and I wasn’t separated because my mother empezó a gritar. You know, she just made a scene. She used her privilege. I thought it was just because she had a big mouth. But no, it was actually later that she told me, “That was my trauma speaking.” But you know, also in many ways, Once I Was You is kind of the way I work as a journalist. I really try to meet people where they are and to find myself in the people most unlike me. And in that sense, Once I Was You is just a broader statement that we share a common humanity.

RENDÓN: That’s a very powerful image. Thank you for sharing that—all of the stories that you describe in your book. You have had an amazing life, if you want to put it that way, an incredible life. Of all these stories, which one do you think was the one that marked you the most?

HINOJOSA: I think Once I Was You captures that it’s all not, you know, no son puras rosas y flores. And along the way, I have met extraordinary people, from very powerful, highly recognized people to people who do not have power at all. Oftentimes, I say that the people who have most changed me are those people, the ones who don’t really have any power but their own will, their own desire to live, their own kind of desire for humanity and justice. Many of them are refugees. But it’s interesting now because I used to say that the story that changed my life the most was 911—having survived that, developing PTSD afterwards, covering it for a year for CNN. But you know, now being a survivor of COVID—I got it early on in the pandemic—and having lived through this, this is a story of our times. I don’t think we quite understand what we have lived through just since the beginning of the pandemic to the end of the year. And then, in large, the last four years under Donald Trump, if you’re Latino or Latina, or an immigrant—a particularly challenging time.

RENDÓN: In relation to that, what do you say to those people that have been describing the behavior of Latinos at the ballot box in a negative sense, because I have heard so many times, especially from mainstream media that, “Latinas didn’t vote for this one candidate that we were expecting,” or “Latinos didn’t do what we wanted them to do?” So what is this obsession of society in general, wanting to direct the lives of Latinos in that way? Do they speak the same about other ethnic groups?

HINOJOSA: You know, we’re really witnessing it, como que it’s right in front of us. We are witnessing what it’s like for Latinos and Latinas to be made into a kind of spectacle by the mainstream media. Yes, I think the mainstream media believes that they’re doing a great job, because they’re talking about us. It’s almost like, “Aren’t you satisfied? We’re talking about Latinos. I mean, isn’t that great?” And what we’re saying is, you are failing to see the bigger picture. I think that there’s just no way in which the mainstream media, in this past election cycle, communicated the truth, which is that Latinos and Latinas are the second-largest voting bloc in the United States of America, period. That is all they need to know. And they should be repeating, and they should have treated this electorate as such. Therefore, there should be Latino and Latina analysts on all of the networks and cable channels, and all of the news sources. And there should be Latino and Latina columnists, from LA to New York to Chicago to everywhere. There should be Latinos and Latinas on the presidential debates. We should be on the presidential debate commission—none of that. So it’s very interesting to see how, at a time when more white voters came out, turned out for Donald Trump, the fascination of the mainstream media is not that, not “What is wrong with white people?” but rather, “What is wrong with Latinos and Latinas?” And actually, the truth is, is that Latinos and Latinas have been voting at about 30% for Republicans for a while and higher than that for George W. Bush. We can’t forget that the Republican Party, for whatever it’s worth, actually go after the Latino vote. They did. They went after the Latino vote in a way that the Democratic Party is like “ehh.” I mean, Bernie Sanders did come out for the Latino/Latina vote, and I think we saw the response, and we saw what happened. But other than that, it’s kind of like, “Well, you’re gonna come out and vote for us anyway.” And that’s just been deeply distressing to witness again, because I’ve been covering elections for a couple of decades now. And again, for the mainstream media, I believe that they are patting themselves on the back and saying “Well, we’re at least talking about you.” Wow. To not recognize that they do not know how to poll Latinos and Latinas and somehow say, “you know, the Latino community is a problem community in terms of polling.” It’s like, no we’re not, if you know how to poll us. The thing is that if you look at Florida, it’s not rocket science to understand kind of how that vote plays out. But you cannot say Florida and its Latinos, as diverse as they are, is the same as what just happened in Arizona, where Latinos and Latinas pushed Arizona blue—in Arizona and Nevada, and even in the Midwest, and in Pennsylvania. In those places, Latinos and Latinas were the back propellor to the black vote. But in places like Arizona and Nevada, we were not the rear push. We were the central push. And that’s a very different story than Latinos and Latinas in Florida.

RENDÓN: Exactly. Now, let me get back to your book. You tell a story about immigration. What are you proposing in terms of the concept of immigration?

HINOJOSA: I have reported on immigration. I understand the complexity of public policy. What I can say is that what is happening now in the United States of America is unacceptable. And people have asked me, “What do we do about the immigration problem?” and I’m like, “Oh, this country does not have an immigration problem, at all.” There’s zero net migration. And refugees are basically down to zero as well. Right now, what this country has is an international human rights crisis, where the only difference is that we were not born here. And because our bodies were not born on the U.S. mainland, we are subject to being denied due process, to having our children taken from us, to being put in cages, to having our uteruses taken out. So, we have children without their parents, and I just find it incredibly hard to believe that a country that says it’s the first in the world for so many things, that this country cannot reunite children with their parents—can’t find them? It should be priority number one. And then, I think the other thing is that you have to really approach immigration from a different mindset. You know, not every person wants to leave their country and come to the United States. It just isn’t true. The caravans from Central America of the refugees were thousands, not tens of thousands. People, if given the opportunity, they want to come here aboveboard legally, as long as you’re not coming after them to rip them away from their families. They will give you everything, all of their personal information, but you carry your end of the deal, which is, “If you come here, and you’re aboveboard, we’re not going to chase you out, and we’re not going to deport you.” To me, these are the basic things about discussing some kind of reform, but it has to be based on humanity and common interest as opposed to the narrative, which is immigrants, Latinos, in particular, are dangerous, demanding, dependent, criminals. None of that is true. None of that is true.

RENDÓN: How guilty do you think mainstream media—we’re getting back to mainstream media—are of these kind of images that people have in their minds in relation to Latinos and Latinas? Because even for professional outlets like the big newspapers, very well-respected networks, they reproduce these stories over and over again, with these kind of images. You have been a journalist for more than 30 years—I’m a journalist as well. So I’m asking you, do you have any ideas on how we can transmit these concepts or these ideas to colleagues that are working for these companies, for them to stop reproducing these ideas.

HINOJOSA: I think what we have to remember is that the mainstream news across the board, almost 100% is owned and operated—and editors in chief—are white men, heterosexual, white men of privilege. And let’s say that they’re at the end of their careers. Now they’re 70 years old, 60 years old. They have grown up watching the same images on the mainstream media that have been repeated, as you say, for decades and decades. So they don’t know any different. You have to recognize that you don’t know any different, and therefore, that’s why you have representation in a newsroom. If you have diversity in your newsroom, they’re gonna say, “Oh, these are images that are incorrect. This does not apply.” And so, I’m not gonna say it’s not that they don’t know any better. I’m saying that they’re victims of the same kind of narratives to which all Americans who consume the news media are victims—these erroneous images of people trying to get into this country massively.

RENDÓN: Is it inertia?

HINOJOSA: Is it inertia? I mean, it’s inertia in the sense that no se van. I mean, where is the creating of space at the senior-most levels in the news networks? We don’t have that much. We have, I think there is one senior Latina at NBC News. We have a couple of anchors, but there isn’t a representation for the kind of population growth and influence that we have in the country. We don’t really see Latinos and Latinas in large enough numbers to make this kind of a difference. The way in which, after Barack Obama was elected, there was a kind of like, “Whoa, we have to really think about how we talk about black men, because a black man is the President of the United States.” We need to have one of those moments, which is like, “Whoa, we really need to rethink how we talk about Latinos and Latinas and immigrants.” But the news media needs to own their responsibility in creating this mess.

HINOJOSA: I think Once I Was You captures that it’s all not, you know, no son puras rosas y flores. And along the way, I have met extraordinary people, from very powerful, highly recognized people to people who do not have power at all. Oftentimes, I say that the people who have most changed me are those people, the ones who don’t really have any power but their own will, their own desire to live, their own kind of desire for humanity and justice. Many of them are refugees. But it’s interesting now because I used to say that the story that changed my life the most was 911—having survived that, developing PTSD afterwards, covering it for a year for CNN. But you know, now being a survivor of COVID—I got it early on in the pandemic—and having lived through this, this is a story of our times. I don’t think we quite understand what we have lived through just since the beginning of the pandemic to the end of the year. And then, in large, the last four years under Donald Trump, if you’re Latino or Latina, or an immigrant—a particularly challenging time.

RENDÓN: In relation to that, what do you say to those people that have been describing the behavior of Latinos at the ballot box in a negative sense, because I have heard so many times, especially from mainstream media that, “Latinas didn’t vote for this one candidate that we were expecting,” or “Latinos didn’t do what we wanted them to do?” So what is this obsession of society in general, wanting to direct the lives of Latinos in that way? Do they speak the same about other ethnic groups?

HINOJOSA: You know, we’re really witnessing it, como que it’s right in front of us. We are witnessing what it’s like for Latinos and Latinas to be made into a kind of spectacle by the mainstream media. Yes, I think the mainstream media believes that they’re doing a great job, because they’re talking about us. It’s almost like, “Aren’t you satisfied? We’re talking about Latinos. I mean, isn’t that great?” And what we’re saying is, you are failing to see the bigger picture. I think that there’s just no way in which the mainstream media, in this past election cycle, communicated the truth, which is that Latinos and Latinas are the second-largest voting bloc in the United States of America, period. That is all they need to know. And they should be repeating, and they should have treated this electorate as such. Therefore, there should be Latino and Latina analysts on all of the networks and cable channels, and all of the news sources. And there should be Latino and Latina columnists, from LA to New York to Chicago to everywhere. There should be Latinos and Latinas on the presidential debates. We should be on the presidential debate commission—none of that. So it’s very interesting to see how, at a time when more white voters came out, turned out for Donald Trump, the fascination of the mainstream media is not that, not “What is wrong with white people?” but rather, “What is wrong with Latinos and Latinas?” And actually, the truth is, is that Latinos and Latinas have been voting at about 30% for Republicans for a while and higher than that for George W. Bush. We can’t forget that the Republican Party, for whatever it’s worth, actually go after the Latino vote. They did. They went after the Latino vote in a way that the Democratic Party is like “ehh.” I mean, Bernie Sanders did come out for the Latino/Latina vote, and I think we saw the response, and we saw what happened. But other than that, it’s kind of like, “Well, you’re gonna come out and vote for us anyway.” And that’s just been deeply distressing to witness again, because I’ve been covering elections for a couple of decades now. And again, for the mainstream media, I believe that they are patting themselves on the back and saying “Well, we’re at least talking about you.” Wow. To not recognize that they do not know how to poll Latinos and Latinas and somehow say, “you know, the Latino community is a problem community in terms of polling.” It’s like, no we’re not, if you know how to poll us. The thing is that if you look at Florida, it’s not rocket science to understand kind of how that vote plays out. But you cannot say Florida and its Latinos, as diverse as they are, is the same as what just happened in Arizona, where Latinos and Latinas pushed Arizona blue—in Arizona and Nevada, and even in the Midwest, and in Pennsylvania. In those places, Latinos and Latinas were the back propellor to the black vote. But in places like Arizona and Nevada, we were not the rear push. We were the central push. And that’s a very different story than Latinos and Latinas in Florida.

RENDÓN: Exactly. Now, let me get back to your book. You tell a story about immigration. What are you proposing in terms of the concept of immigration?

HINOJOSA: I have reported on immigration. I understand the complexity of public policy. What I can say is that what is happening now in the United States of America is unacceptable. And people have asked me, “What do we do about the immigration problem?” and I’m like, “Oh, this country does not have an immigration problem, at all.” There’s zero net migration. And refugees are basically down to zero as well. Right now, what this country has is an international human rights crisis, where the only difference is that we were not born here. And because our bodies were not born on the U.S. mainland, we are subject to being denied due process, to having our children taken from us, to being put in cages, to having our uteruses taken out. So, we have children without their parents, and I just find it incredibly hard to believe that a country that says it’s the first in the world for so many things, that this country cannot reunite children with their parents—can’t find them? It should be priority number one. And then, I think the other thing is that you have to really approach immigration from a different mindset. You know, not every person wants to leave their country and come to the United States. It just isn’t true. The caravans from Central America of the refugees were thousands, not tens of thousands. People, if given the opportunity, they want to come here aboveboard legally, as long as you’re not coming after them to rip them away from their families. They will give you everything, all of their personal information, but you carry your end of the deal, which is, “If you come here, and you’re aboveboard, we’re not going to chase you out, and we’re not going to deport you.” To me, these are the basic things about discussing some kind of reform, but it has to be based on humanity and common interest as opposed to the narrative, which is immigrants, Latinos, in particular, are dangerous, demanding, dependent, criminals. None of that is true. None of that is true.

RENDÓN: How guilty do you think mainstream media—we’re getting back to mainstream media—are of these kind of images that people have in their minds in relation to Latinos and Latinas? Because even for professional outlets like the big newspapers, very well-respected networks, they reproduce these stories over and over again, with these kind of images. You have been a journalist for more than 30 years—I’m a journalist as well. So I’m asking you, do you have any ideas on how we can transmit these concepts or these ideas to colleagues that are working for these companies, for them to stop reproducing these ideas.

HINOJOSA: I think what we have to remember is that the mainstream news across the board, almost 100% is owned and operated—and editors in chief—are white men, heterosexual, white men of privilege. And let’s say that they’re at the end of their careers. Now they’re 70 years old, 60 years old. They have grown up watching the same images on the mainstream media that have been repeated, as you say, for decades and decades. So they don’t know any different. You have to recognize that you don’t know any different, and therefore, that’s why you have representation in a newsroom. If you have diversity in your newsroom, they’re gonna say, “Oh, these are images that are incorrect. This does not apply.” And so, I’m not gonna say it’s not that they don’t know any better. I’m saying that they’re victims of the same kind of narratives to which all Americans who consume the news media are victims—these erroneous images of people trying to get into this country massively.

RENDÓN: Is it inertia?

HINOJOSA: Is it inertia? I mean, it’s inertia in the sense that no se van. I mean, where is the creating of space at the senior-most levels in the news networks? We don’t have that much. We have, I think there is one senior Latina at NBC News. We have a couple of anchors, but there isn’t a representation for the kind of population growth and influence that we have in the country. We don’t really see Latinos and Latinas in large enough numbers to make this kind of a difference. The way in which, after Barack Obama was elected, there was a kind of like, “Whoa, we have to really think about how we talk about black men, because a black man is the President of the United States.” We need to have one of those moments, which is like, “Whoa, we really need to rethink how we talk about Latinos and Latinas and immigrants.” But the news media needs to own their responsibility in creating this mess.

RENDÓN: Your book is also published in Spanish with the title, Una vez fui tú. What does it mean for you? Because normally, publishers don’t publish the same book in both English and Spanish. So what does it mean for you? Was it a request from you to publish it in Spanish?

HINOJOSA: I did want to have the book in Spanish. It is not a market-based decision for me. But I do feel that it makes a statement, and it has brought me great joy to see multigenerational younger women reading it in English and their moms reading it in Spanish. We’re doing an Instagram takeover where we’re publishing their photos of people reading the book, just so people can see the different faces of people reading Once I Was You. That has been one of my great joys, to see [someone say], “My mom is reading it in Spanish.” I really would love to sit down and have a conversation with them because I did not write the book in Spanish, and it was really hard. The translation part of it was very painful for me because I write very . . . it’s just like the way I talk. It’s more kind of just very real, authentic, the way one talks because I write for radio, oftentimes.

RENDÓN: Similar to a stream of consciousness?

HINOJOSA: Un poco. I mean, we edit it down so that it makes sense, but when I’m writing, that is kind of what I’m doing. I’m like, “Oh, my God, and then this happened, and then this happened, and then this happened.” And cuando estoy hablando en español es otra cosa. And I would have had to have told the same stories all over again in Spanish to get “like me.” Somebody would have had to have said, “No pero entonces cuentame qué pasó en ese momento,” so that I could say it in Spanish, and maybe get closer. But what I’m trying to say is that one of the fundamental, I hope, messages in the book is of course, we have to love ourselves. But that particular notion of ni soy de aquí ni soy de allá, I actually, I’m trying to say that is our superpower, y sí soy de aquí, y soy de allá. And I do speak multiple languages. Maybe not each at 100%, but at least I’m speaking two languages, or three or four. I’m always trying to flip the narrative for the reader, for Latinos and Latinas in this country to say, “This is our superpower.” Don’t feel negative about it. Be proud, own it.

RENDÓN: And that is very interesting, because in some places around the United States, of course, there are people who don’t want their kids to suffer discrimination. And they don’t teach them Spanish. I agree with you. It’s a superpower to speak both languages and being from both places at the same time. So, you mentioned love already, and I wanted to ask you about that. What is the part of the book that you love the most?

HINOJOSA: Probably my story as a woman. I think this was, for me, one of the things to recognize, my power as a woman. And that extends to as a woman journalist, as a mom, as a wife, as a friend, as a role model. I think this was part of what I did want to kind of share. But that’s an interesting question. No one’s really asked me that question. I could say, also, the experience of being an immigrant. I’m very hopeful. My dream is that the little girl who I meet in the airport—now it’s two years, almost—maybe she’s in the United States. Maybe by now she’s already fluent in English. Maybe she gets a hold of this book in English or in Spanish, and she sees herself and recognizes her own power. So I think there are multiple ways in which I can see that there was love and power in writing these particular stories. One of the things that has been fascinating for me, is having people say, “Ay Maria, but you know, you’re so successful.” By the way, I’ve been doing this for a while. So yeah, I would hope so. Pero they’re like, “Oh, my God, you’re so successful. Why would you want to reveal that you’re insecure, or that you battled the imposter syndrome?” I don’t believe that journalism is something that you do to make a lot of money. Some people can, hey, bravo. But to me, it’s more like a service. And so if I’m going to continue to be of service, I’m like, well sabes qué, let me tell you about some of the things that I’ve experienced that really are a waste of our emotional, psychological time. Feeling the imposter syndrome is real, but it’s better to just talk about it and try to push through it than to just have it forever and ever and ever. And that’s why I wanted to write about it.

RENDÓN: I really like how the book reads in a very powerful way. And of course, it shows the different facets of people as successful as you, as you were saying, but that everybody’s human at the end, and that everybody has to overcome struggles. I think it’s remarkable. Your story is remarkable.

HINOJOSA: Thank you.

RENDÓN: I’ve seen that you are very active on social media, and you engage with your followers. So, in what way, besides that one, do you want to connect with your readers? I guess what I’m asking is, what do you expect the readers to get out of your book?

HINOJOSA: When you’re writing something like this, I was not writing per se, with an expectation of what am I going to create for the reader. As a writer, if you start out that way, it’s a challenge. So for me, it was more, how can I be the most honest and authentic about my experience? And in that sense, when you ask, “How do I want to connect with the readers?”, well I want them to see that we all have this deep power inside of us, that capacity to survive, fight all kinds of challenges—that’s something that is important to me. There is that scene in Once I Was You where I’m kind of like, “Oh, my God, I’m about to go on National Public Radio for the first time on NPR. And I’ve got to kind of decide what’s going to happen?” Am I Maria Hinojosa? [English accent] or am I going to be Maria Hinojosa? [Spanish accent] And I realized at that moment, as I write in the book, I was like, “Okay, well, this is a very personal decision right now. But actually, whatever you do, it’s going to have consequences.” And in that sense, I hope to be very approachable, very honest, hoping that people feel touched by my work. That, on a personal level, they can identify with me, but that, at a broader level, they can identify with what I’m talking about—reckoning with American history and how it has treated people of color, Latinos and Latinas, and immigrants historically in this country.

RENDÓN: You have accomplished that in several ways with this book. And also, you are a role model for a lot of people. So I think that level of honesty is essential for people who see you as an icon of Latinas to understand that it’s not beneath you, right?

HINOJOSA: I just think it’s funny when people are like, “You’re an icon,” and I’m like, “Umm, I’m five feet tall.” [Laughs] Yes, I have success, but you know, there’s a lot of fight that comes with that—fighting against my own insecurities to push through. So I think right now, in our country, this is a moment where—especially living through a pandemic, you know—we’re living at home and working from home. It’s a time in which we can really say, “I’m just like you.” And I think that’s one thing that we have experienced, a lot of the filters have come off.

RENDÓN: Lastly, let me ask you, who are your role models? I said, you’re a role model for a lot of people, not only women but also for many men who find your story fascinating. But, who are the people who have influenced your thinking, your life, even your writing?

HINOJOSA: Uff, I mean, a long list of women and men. I’m getting ready to go to Mexico to see my mother who I haven’t seen in almost two years, so I have to go see her. She is certainly one of my greatest role models, and she’s still a firecracker in her 80s—still going strong. And there are so many powerful women that I have met. I mean, oh my goodness!—people like Sonia Sotomayor, who I’ve been able to meet and interview and actually hang out with. You know, how does Sonia move in this world as a Supreme Court justice? You know, Sandra Cisneros is a great role model for me. And Sandra Cisneros, I’m friends with her, with Julia Alvarez, with Anna Castillo, Denise Chávez, the great Latina writers. But I’m also friends with newer Latina writers, Jessica Salgado, or Elizabeth Acevedo, younger writers. I’m getting to know them and their work, so I feel influenced by them. And then there’s the great feminist, I mean, my God, Gloria Steinem gave a blurb for my book, Jane Fonda gave a blurb for my . . . [Laughs] It’s like, what? And so I learned from them. I think what you learn in the book is that there are some key people in my life, my best friend Sandy, who’s African American, Cecilia Vaisman, may she rest in peace, these few women who are kind of solid core friends, my Latinas in power group. For me, a role model is, you know, from Cardi B, who I’m dying to interview one day to the woman refugee, who crossed into the United States with fear to save herself and her daughter’s life, who is living underground in this country with no plans, nothing, but thankful to be alive. Those women are my role models too.

RENDÓN: I wish we had more time for this interview Maria, but muchas gracias.

HINOJOSA: Thank you so much for the work that you’re doing. You may not know this, but the work that you do, and the fact that you’re doing this work is really important. It is part of our narrative. And so I’m thrilled and honored to have been interviewed, and congratulations and más.

RENDÓN: Vamos por más. Muchas gracias Maria.

HINOJOSA: I did want to have the book in Spanish. It is not a market-based decision for me. But I do feel that it makes a statement, and it has brought me great joy to see multigenerational younger women reading it in English and their moms reading it in Spanish. We’re doing an Instagram takeover where we’re publishing their photos of people reading the book, just so people can see the different faces of people reading Once I Was You. That has been one of my great joys, to see [someone say], “My mom is reading it in Spanish.” I really would love to sit down and have a conversation with them because I did not write the book in Spanish, and it was really hard. The translation part of it was very painful for me because I write very . . . it’s just like the way I talk. It’s more kind of just very real, authentic, the way one talks because I write for radio, oftentimes.

RENDÓN: Similar to a stream of consciousness?

HINOJOSA: Un poco. I mean, we edit it down so that it makes sense, but when I’m writing, that is kind of what I’m doing. I’m like, “Oh, my God, and then this happened, and then this happened, and then this happened.” And cuando estoy hablando en español es otra cosa. And I would have had to have told the same stories all over again in Spanish to get “like me.” Somebody would have had to have said, “No pero entonces cuentame qué pasó en ese momento,” so that I could say it in Spanish, and maybe get closer. But what I’m trying to say is that one of the fundamental, I hope, messages in the book is of course, we have to love ourselves. But that particular notion of ni soy de aquí ni soy de allá, I actually, I’m trying to say that is our superpower, y sí soy de aquí, y soy de allá. And I do speak multiple languages. Maybe not each at 100%, but at least I’m speaking two languages, or three or four. I’m always trying to flip the narrative for the reader, for Latinos and Latinas in this country to say, “This is our superpower.” Don’t feel negative about it. Be proud, own it.

RENDÓN: And that is very interesting, because in some places around the United States, of course, there are people who don’t want their kids to suffer discrimination. And they don’t teach them Spanish. I agree with you. It’s a superpower to speak both languages and being from both places at the same time. So, you mentioned love already, and I wanted to ask you about that. What is the part of the book that you love the most?

HINOJOSA: Probably my story as a woman. I think this was, for me, one of the things to recognize, my power as a woman. And that extends to as a woman journalist, as a mom, as a wife, as a friend, as a role model. I think this was part of what I did want to kind of share. But that’s an interesting question. No one’s really asked me that question. I could say, also, the experience of being an immigrant. I’m very hopeful. My dream is that the little girl who I meet in the airport—now it’s two years, almost—maybe she’s in the United States. Maybe by now she’s already fluent in English. Maybe she gets a hold of this book in English or in Spanish, and she sees herself and recognizes her own power. So I think there are multiple ways in which I can see that there was love and power in writing these particular stories. One of the things that has been fascinating for me, is having people say, “Ay Maria, but you know, you’re so successful.” By the way, I’ve been doing this for a while. So yeah, I would hope so. Pero they’re like, “Oh, my God, you’re so successful. Why would you want to reveal that you’re insecure, or that you battled the imposter syndrome?” I don’t believe that journalism is something that you do to make a lot of money. Some people can, hey, bravo. But to me, it’s more like a service. And so if I’m going to continue to be of service, I’m like, well sabes qué, let me tell you about some of the things that I’ve experienced that really are a waste of our emotional, psychological time. Feeling the imposter syndrome is real, but it’s better to just talk about it and try to push through it than to just have it forever and ever and ever. And that’s why I wanted to write about it.

RENDÓN: I really like how the book reads in a very powerful way. And of course, it shows the different facets of people as successful as you, as you were saying, but that everybody’s human at the end, and that everybody has to overcome struggles. I think it’s remarkable. Your story is remarkable.

HINOJOSA: Thank you.

RENDÓN: I’ve seen that you are very active on social media, and you engage with your followers. So, in what way, besides that one, do you want to connect with your readers? I guess what I’m asking is, what do you expect the readers to get out of your book?

HINOJOSA: When you’re writing something like this, I was not writing per se, with an expectation of what am I going to create for the reader. As a writer, if you start out that way, it’s a challenge. So for me, it was more, how can I be the most honest and authentic about my experience? And in that sense, when you ask, “How do I want to connect with the readers?”, well I want them to see that we all have this deep power inside of us, that capacity to survive, fight all kinds of challenges—that’s something that is important to me. There is that scene in Once I Was You where I’m kind of like, “Oh, my God, I’m about to go on National Public Radio for the first time on NPR. And I’ve got to kind of decide what’s going to happen?” Am I Maria Hinojosa? [English accent] or am I going to be Maria Hinojosa? [Spanish accent] And I realized at that moment, as I write in the book, I was like, “Okay, well, this is a very personal decision right now. But actually, whatever you do, it’s going to have consequences.” And in that sense, I hope to be very approachable, very honest, hoping that people feel touched by my work. That, on a personal level, they can identify with me, but that, at a broader level, they can identify with what I’m talking about—reckoning with American history and how it has treated people of color, Latinos and Latinas, and immigrants historically in this country.

RENDÓN: You have accomplished that in several ways with this book. And also, you are a role model for a lot of people. So I think that level of honesty is essential for people who see you as an icon of Latinas to understand that it’s not beneath you, right?

HINOJOSA: I just think it’s funny when people are like, “You’re an icon,” and I’m like, “Umm, I’m five feet tall.” [Laughs] Yes, I have success, but you know, there’s a lot of fight that comes with that—fighting against my own insecurities to push through. So I think right now, in our country, this is a moment where—especially living through a pandemic, you know—we’re living at home and working from home. It’s a time in which we can really say, “I’m just like you.” And I think that’s one thing that we have experienced, a lot of the filters have come off.

RENDÓN: Lastly, let me ask you, who are your role models? I said, you’re a role model for a lot of people, not only women but also for many men who find your story fascinating. But, who are the people who have influenced your thinking, your life, even your writing?

HINOJOSA: Uff, I mean, a long list of women and men. I’m getting ready to go to Mexico to see my mother who I haven’t seen in almost two years, so I have to go see her. She is certainly one of my greatest role models, and she’s still a firecracker in her 80s—still going strong. And there are so many powerful women that I have met. I mean, oh my goodness!—people like Sonia Sotomayor, who I’ve been able to meet and interview and actually hang out with. You know, how does Sonia move in this world as a Supreme Court justice? You know, Sandra Cisneros is a great role model for me. And Sandra Cisneros, I’m friends with her, with Julia Alvarez, with Anna Castillo, Denise Chávez, the great Latina writers. But I’m also friends with newer Latina writers, Jessica Salgado, or Elizabeth Acevedo, younger writers. I’m getting to know them and their work, so I feel influenced by them. And then there’s the great feminist, I mean, my God, Gloria Steinem gave a blurb for my book, Jane Fonda gave a blurb for my . . . [Laughs] It’s like, what? And so I learned from them. I think what you learn in the book is that there are some key people in my life, my best friend Sandy, who’s African American, Cecilia Vaisman, may she rest in peace, these few women who are kind of solid core friends, my Latinas in power group. For me, a role model is, you know, from Cardi B, who I’m dying to interview one day to the woman refugee, who crossed into the United States with fear to save herself and her daughter’s life, who is living underground in this country with no plans, nothing, but thankful to be alive. Those women are my role models too.

RENDÓN: I wish we had more time for this interview Maria, but muchas gracias.

HINOJOSA: Thank you so much for the work that you’re doing. You may not know this, but the work that you do, and the fact that you’re doing this work is really important. It is part of our narrative. And so I’m thrilled and honored to have been interviewed, and congratulations and más.

RENDÓN: Vamos por más. Muchas gracias Maria.

Comment Box is loading comments...

|

|