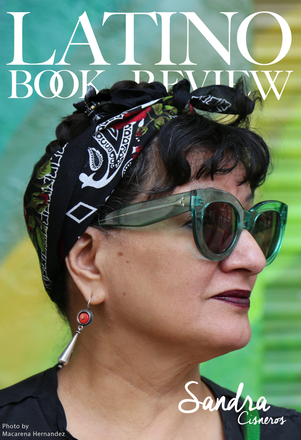

Interview with Sandra Cisneros

Sandra Cisneros is an activist poet, short story writer, novelist, essayist and artist. Writing for over 50 years, her work explores the lives of the working-class. Her numerous awards include NEA fellowships in both poetry and prose, the Texas Medal of the Arts, a MacArthur Fellowship, several honorary degrees, and both national and international book awards. Most recently, she received the Ford Foundation's Art of Change Fellowship, Chicago's Fifth Star Award, the PEN Center USA Literary Award, the Arthur R. Velasquez Award from the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago and Loyola University's Arts & Science Damen Award, presented to Loyola alumni in recognition of their leadership in industry, the community, and service to others. She received the 2015 National Medal of Arts presented to her by President Obama at the White House, she received the Congressional Hispanic Caucus Institute's 2017 CHCI Chair's Award in Washington, D.C., and The Texas Institute of Letters's Lifetime Achievement Award 2018.

Her classic coming-of-age novel, The House on Mango Street has sold over six million copies, has been translated into more than twenty languages, and is required reading in elementary, high school, and university curricula across the U.S.

Founder of awards and foundations, and a dual citizen of Mexico and the Unites States, she currently makes her home in the state of Guanajuato, home of her ancestors.

GERALD PADILLA: Sandra, it is an honor to have you, one of the leading figures of Latino and American contemporary literature, on Latino Book Review.

SANDRA CISNEROS: It’s kind of you to give me this platform.

SANDRA CISNEROS: It’s kind of you to give me this platform.

|

PADILLA: Your journey as a writer began to unfold when you took your first creative writing class in 1974. Since then, you have received some of the most prestigious literary awards this country has to offer, and have sold millions of copies of your books which have been translated into over twenty languages.

As a spectator, one tends to focus on snapshots of triumph and success, but at times we fail to see all of the years of hard work that goes behind the scenes to build a literary career such as yours. Can you tell us about some of the sacrifices that you’ve made throughout your journey to become the writer you are today? And, did you foresee your career as a writer unfold the way it has when you first started? CISNEROS: My journey as an artist began before 1974. It began when I was a child in the way that I looked at the world and interpreted it, first in drawings and later in middle school through language, but it’s all from the same source. |

Sandra as a schoolgirl

Photo ©2014 Sandra Cisneros |

I never expected more from my writing career than the good opinion of other writers, so, of course, I’m startled by my life. I was/am essentially an introvert, but my career demands I meet my public, which is antithetical to writing, but it allows me to do the spiritual work of delivering the stories and poems to those who need to hear them. What I do on paper and in person I consider work of the spirit.

Sacrifices? Everybody makes sacrifices. My father and mother had to work very hard, as did their parents. I think my life is pretty easy compared to them. I have to deal with getting on planes when I’m afraid of flying, meeting deadlines, speaking in front of a public, sumo wrestling with my writing, trying to write about subjects that will help right the planet when it’s off its axis, trying to heal people with what I say/write, but all this is within my capacity, and not as difficult as those who came before me. I think one of the great difficulties of being a writer is that I do things differently from most of society, and that makes them think of me as “eccentric,” but I live by my heart, by my truth, and that makes everyone else look like “eccentrics” to me.

I am a single woman without children living far from family, in another country, who has no intention of living with someone. Does that make me look crazy? Maybe to my relatives, but not to artists friends, who understand why I live as I do.

If I had to speak about anything that was difficult in my life now looking back at it, I would say the most difficult part was how the world made you feel about being poor, about being a girl. And, later, how painful it was navigating the world as a young woman. A lot of times I found myself in disastrous situations because I was such an innocent/idiot. It left me damaged as a human being for decades. I think having been beautiful was a cross, and I’m grateful I’m no longer young and no longer beautiful in that same way.

PADILLA: In the past you’ve mentioned how you didn’t feel “smart enough” as a student, probably because you constantly had to be moving around to different homes and schools as a child. Ironically, your work has become widely studied throughout the American public school system and academia. How does this scholastic acceptance make you feel in reference to how you felt about yourself as a child? And, what would you say to some of our youth who may feel like they are not “smart enough” as students?

CISNEROS: I’ve already written about this in my essay “A Girl Called Daydreamer,” but to sum it up, I was not measured for the greatest gift I was born with, creativity. I’m lucky I survived to be an artist at all given my first report cards and the attitude of my early teachers.

I think we are all gifted as children, but we aren’t gifted with the same gifts. In crowded, poor schools, an overwhelmed teacher can’t always help us discover what our gifts are. I am grateful my mom was a frustrated artist. At home we drew murals, created puppet shows, had craft hours, went to the library, visited museums. I’m certain without my mom, I wouldn’t have been an artist today.

Sacrifices? Everybody makes sacrifices. My father and mother had to work very hard, as did their parents. I think my life is pretty easy compared to them. I have to deal with getting on planes when I’m afraid of flying, meeting deadlines, speaking in front of a public, sumo wrestling with my writing, trying to write about subjects that will help right the planet when it’s off its axis, trying to heal people with what I say/write, but all this is within my capacity, and not as difficult as those who came before me. I think one of the great difficulties of being a writer is that I do things differently from most of society, and that makes them think of me as “eccentric,” but I live by my heart, by my truth, and that makes everyone else look like “eccentrics” to me.

I am a single woman without children living far from family, in another country, who has no intention of living with someone. Does that make me look crazy? Maybe to my relatives, but not to artists friends, who understand why I live as I do.

If I had to speak about anything that was difficult in my life now looking back at it, I would say the most difficult part was how the world made you feel about being poor, about being a girl. And, later, how painful it was navigating the world as a young woman. A lot of times I found myself in disastrous situations because I was such an innocent/idiot. It left me damaged as a human being for decades. I think having been beautiful was a cross, and I’m grateful I’m no longer young and no longer beautiful in that same way.

PADILLA: In the past you’ve mentioned how you didn’t feel “smart enough” as a student, probably because you constantly had to be moving around to different homes and schools as a child. Ironically, your work has become widely studied throughout the American public school system and academia. How does this scholastic acceptance make you feel in reference to how you felt about yourself as a child? And, what would you say to some of our youth who may feel like they are not “smart enough” as students?

CISNEROS: I’ve already written about this in my essay “A Girl Called Daydreamer,” but to sum it up, I was not measured for the greatest gift I was born with, creativity. I’m lucky I survived to be an artist at all given my first report cards and the attitude of my early teachers.

I think we are all gifted as children, but we aren’t gifted with the same gifts. In crowded, poor schools, an overwhelmed teacher can’t always help us discover what our gifts are. I am grateful my mom was a frustrated artist. At home we drew murals, created puppet shows, had craft hours, went to the library, visited museums. I’m certain without my mom, I wouldn’t have been an artist today.

|

When you purchase a book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission and so do independent book stores.

|

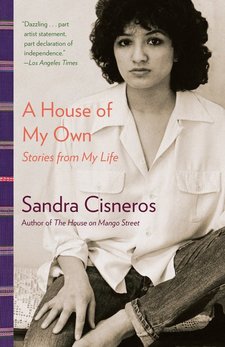

PADILLA: Your book, A House of My Own, is a collection of personal essays that explore and document important parts of your life from your early days in Chicago to your current home in Guanajuato. In it, we find constant themes of search and belonging. What have you found in your current home in Guanajuato that maybe had been missing in all the other places where you’ve lived?

CISNEROS: I like living in a town not dominated by cars. I like living in a small community where artists from around the world come and go. I like living in a town with big sky and big clouds, and where you can connect with things of the spirit easily. It’s both stimulating and peaceful all at once. It makes me want to write. PADILLA: Tell us about your most recent book, Puro Amor, which is now available for pre-order. CISNEROS: My latest book, Puro Amor, is a bilingual chapbook translated by my dear friend, Liliana Valenzuela, just published by Sarabande Books in Kentucky. It is the first time I have ever used my own drawings to illustrate a book. It has been a wonderful experience. |

|

PADILLA: In your book, A House of My Own, you also write about the “Age of susto” that we currently live in, the age of fear. In the U.S., the fear has become palpable on so many levels, not only within our Latino community but with minorities across the board. Internationally, we see a similar phenomenon. What do you do to seek solace in this “Age of susto”, and what can we do to help shake it off collectively?

CISNEROS: I think reading books by people I admire who are/were activists helps guide me in my speaking and writing. I love Thich Nhat Hanh and the works of poet Joy Harjo, and, of course, Gandhi. I love documentaries about people who motivate me to be brave. I am constantly searching for the way to make peace in the world. My life is a lifelong search to be of value, to be of service. Writers like Elena Poniatowska, Gwendolyn Brooks, Eduardo Galeano, for example, are my North Stars. |

When you purchase a book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission and so do independent book stores.

|

PADILLA: In 2016, you received the highest award given to artists by the United States government, the 2015 Medal of Arts presented by President Obama at the White House. What went through your mind when you were first given the news regarding this recognition? Was this an outcome that you had hoped for as a writer or was this something unexpected?

CISNEROS: I don’t feel awards are that important TO ME at this level in my career, and I would’ve preferred to stay home writing that day, but I had to go to collect the award to represent my community. I personally had to wrestle whether to attend because of Obama’s record with the deportation of undocumented immigrants. I felt and feel conflicted about appearing anywhere with a politician since politicians have more to gain than I do from our encounters.

It is difficult for me to be at any event where I am not allowed to speak. In order to counter this, when I visited the White House I dressed in my most striking Mexican outfit, so that I could speak through my clothes.

PADILLA: What are some life lessons you’ve learned throughout your journey as a writer that might be helpful to other Latino artists who are starting their journey?

It is difficult for me to be at any event where I am not allowed to speak. In order to counter this, when I visited the White House I dressed in my most striking Mexican outfit, so that I could speak through my clothes.

PADILLA: What are some life lessons you’ve learned throughout your journey as a writer that might be helpful to other Latino artists who are starting their journey?

|

CISNEROS:

1. Assume you won’t make money from your art; always have a day job or two. Make SURE you earn your own money and are not accepting it from someone else, anyone else. This way you control your destiny. You may never earn from your art or become famous; are you okay with this? 2. Control your fertility. You may not be able to afford having a child in your lifetime. Are you okay with this? 3. Solitude is sacred. This is time for you to develop your art. Don’t waste this valuable time. Are you okay with possibly living your life without a partner? PADILLA: Before we conclude this interview, would you mind sharing a final thought with the Latino community? |

CISNEROS: What a terrible time we are witnessing for Latinos in the world. The only good thing that can come from it is if it motivates us to act to do something positive to right the wrongs we witness daily. We must be so disgusted by what we are witnessing that we rise up and become a hero, even if being a hero means only opening our mouths and speaking.

PADILLA: Sandra, thank you for sharing your journey and vision with us. It was a pleasure to have you on Latino Book Review. De todo corazón, we wish you the best.

CISNEROS: Gracias.

PADILLA: Sandra, thank you for sharing your journey and vision with us. It was a pleasure to have you on Latino Book Review. De todo corazón, we wish you the best.

CISNEROS: Gracias.

Comment Box is loading comments...

|

|