Flashes, Disconnections and Missed Connections:

An Interview with Robert Lopez Regarding His New Book,

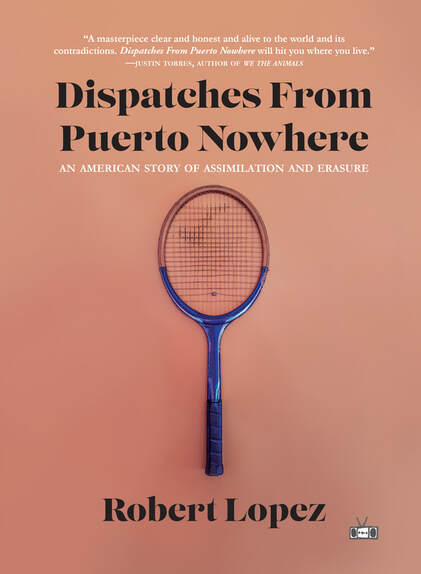

Dispatches from Puerto Nowhere

By Daniel A. Olivas

Robert Lopez lives in Brooklyn and is best known for his fiction which includes three novels, two story collections, and one novel-in-stories. His novel, Kamby Bolongo Mean River, was named one of 25 important books of the last decade by HTML Giant. Lopez’s fiction, nonfiction, and poetry have appeared in many publications, including The Threepenny Review, The Sun, Bomb, Vice Magazine, New England Review, and the Norton Anthology of Sudden Fiction – Latino. Lopez teaches at Stony Brook University and has previously taught at Columbia University, The New School, Pratt Institute, and Syracuse University. In short, he is living the writing life.

Sam Lipsyte once called Lopez’s fiction original and fearless. The same can be said of his nonfiction with the publication of Dispatches From Puerto Nowhere: An American Story of Assimilation and Erasure (Two Dollar Radio). In this not-quite-a-memoir exploration of his life as an “assimilated” Puerto Rican, Lopez uses dispatches—some hilarious, others heartbreaking—to explain and interrogate his life to an unknown recipient who could very well be himself. Imagine messages in a bottle written by an extremely talented and thoughtful explorer of a land called assimilation. As he observes at one point:

“That I was born Puerto Rican was happenstance, but that I have no connection to what it means is no accident. My grandparents made conscious decisions and so did my father as part of the first generation born here in the States. And none of it bothered me until recently, which is probably why I can’t quite put my finger on any of this. I’m still grappling with what I’ve lost and how I can miss something I’ve never had.”

Sam Lipsyte once called Lopez’s fiction original and fearless. The same can be said of his nonfiction with the publication of Dispatches From Puerto Nowhere: An American Story of Assimilation and Erasure (Two Dollar Radio). In this not-quite-a-memoir exploration of his life as an “assimilated” Puerto Rican, Lopez uses dispatches—some hilarious, others heartbreaking—to explain and interrogate his life to an unknown recipient who could very well be himself. Imagine messages in a bottle written by an extremely talented and thoughtful explorer of a land called assimilation. As he observes at one point:

“That I was born Puerto Rican was happenstance, but that I have no connection to what it means is no accident. My grandparents made conscious decisions and so did my father as part of the first generation born here in the States. And none of it bothered me until recently, which is probably why I can’t quite put my finger on any of this. I’m still grappling with what I’ve lost and how I can miss something I’ve never had.”

|

Lopez eloquently expresses the anger, frustration, and even bemusement of someone who—as a successful middle-aged writer—is grappling with the seemingly irreparable loss of cultural identity. In doing so, Lopez allows himself to become deeply vulnerable by offering nothing but the awful truth though often salted with his trademark mordant humor where he and his family are often the target. This is a sharply written, incisive, and extremely engaging meditation on assimilation that will strike a painful chord with many who have suffered from the same erasure of their culture in this country.

DANIEL A. OLIVAS: While hard to classify this latest book of yours, it is, in some ways, a memoir that takes the form of “dispatches” from both physical places and ethereal head spaces. Could you talk about your decision to avoid the more traditional memoir form in crafting this very personal book? ROBERT LOPEZ: While I sometimes enjoy reading traditional memoirs, I’ve never been interested in doing such a thing myself. This book started as a collection of braided essays that were often personal, but nothing that I’d classify as memoir, per se. Ultimately, the final form of the book reflects the real-life experience. Flashes, disconnections, missed connections, short bursts, tangential episodes. I rarely do anything in a traditional, linear fashion because that’s not how I experience this world, particularly as a writer. I wouldn’t know how to write a traditional memoir just like I wouldn’t know how to write a page-turner novel, so it was never a real decision. |

When you purchase a book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission and so do independent book stores.

|

OLIVAS: The subtitle of your book is: An American Story of Assimilation and Erasure. As the grandson of Mexican immigrants who grew up in a household where Spanish had been banished by a white doctor who told my parents that they were just confusing me with a language beyond English, your book really struck a nerve. Did that sense of cultural erasure serve as the driving force in writing this book? In other words, is this your attempt at reclamation of your Puerto Rican heritage?

LOPEZ: Erasure is a dominant theme of the book, for sure. I never set out to examine cultural erasure as subject matter, but like everything I’ve ever done on the page it presented itself as what I was doing once I’d already started putting this language together. The book started with a meditation on the word “spic” and before long all of this other stuff happened. I also wouldn’t say that I’m trying to reclaim my Puerto Rican heritage. I pretty much feel the same way I did when I started the book. Nothing has changed as a result of writing the book or living inside of it for the last four or five years. I do wish it were otherwise, though. If anything, the book says this is what’s happened to me and my family and I know it has happened to countless others and isn’t it interesting, sad, beautiful in some ways, and something to think about.

OLIVAS: Throughout the book, you return to the question of what kind of life your late grandfather, Sixto Lopez, had in Puerto Rico before moving to the mainland and settling in New York. Because you are a fiction writer, you know how to invent lives, and you do some of that to help fill in the blanks of Sixto’s experiences, sometimes offering alternative scenarios. In some ways, those portions of your book are the most heartbreaking. If you could sit down and have a drink with Sixto, what would be some of the questions you’d ask him?

LOPEZ: Certainly, who were your parents, did you have siblings, what did they do, did you come to Brooklyn alone, ever consider going elsewhere, what did you miss about Puerto Rico, what was lifelike there, did you choose to make sure your children assimilate into the American culture as quickly as possible or did it just happen?

OLIVAS: Has writing this book revealed anything to you about your cultural identity?

LOPEZ: I’m afraid not. It’s pretty clear, though, that a lot of people have had similar experiences and to make those connections is a good feeling.

LOPEZ: Erasure is a dominant theme of the book, for sure. I never set out to examine cultural erasure as subject matter, but like everything I’ve ever done on the page it presented itself as what I was doing once I’d already started putting this language together. The book started with a meditation on the word “spic” and before long all of this other stuff happened. I also wouldn’t say that I’m trying to reclaim my Puerto Rican heritage. I pretty much feel the same way I did when I started the book. Nothing has changed as a result of writing the book or living inside of it for the last four or five years. I do wish it were otherwise, though. If anything, the book says this is what’s happened to me and my family and I know it has happened to countless others and isn’t it interesting, sad, beautiful in some ways, and something to think about.

OLIVAS: Throughout the book, you return to the question of what kind of life your late grandfather, Sixto Lopez, had in Puerto Rico before moving to the mainland and settling in New York. Because you are a fiction writer, you know how to invent lives, and you do some of that to help fill in the blanks of Sixto’s experiences, sometimes offering alternative scenarios. In some ways, those portions of your book are the most heartbreaking. If you could sit down and have a drink with Sixto, what would be some of the questions you’d ask him?

LOPEZ: Certainly, who were your parents, did you have siblings, what did they do, did you come to Brooklyn alone, ever consider going elsewhere, what did you miss about Puerto Rico, what was lifelike there, did you choose to make sure your children assimilate into the American culture as quickly as possible or did it just happen?

OLIVAS: Has writing this book revealed anything to you about your cultural identity?

LOPEZ: I’m afraid not. It’s pretty clear, though, that a lot of people have had similar experiences and to make those connections is a good feeling.

Comment Box is loading comments...

|

|