Fiction as the Distillation and Reconstruction of Reality: An Interview with Frederick Luis Aldama regarding The Absolutely (Almost) True Adventures of Max Rodriguez

By Daniel A. Olivas

Frederick Luis Aldama is one of the most prolific writers around. Known as Professor Latinx, he is an award-winning author and editor of over 50 books for young children, teenagers, and adults. Born in Mexico City to a Guatemalan- and Irish-American mother from Los Angeles and a Mexican father from Mexico City, Aldama currently holds the Jacob & Frances Sanger Mossiker Chair in the Humanities at the University of Texas, Austin, and serves on the board of directors for The Academy of American Poets.

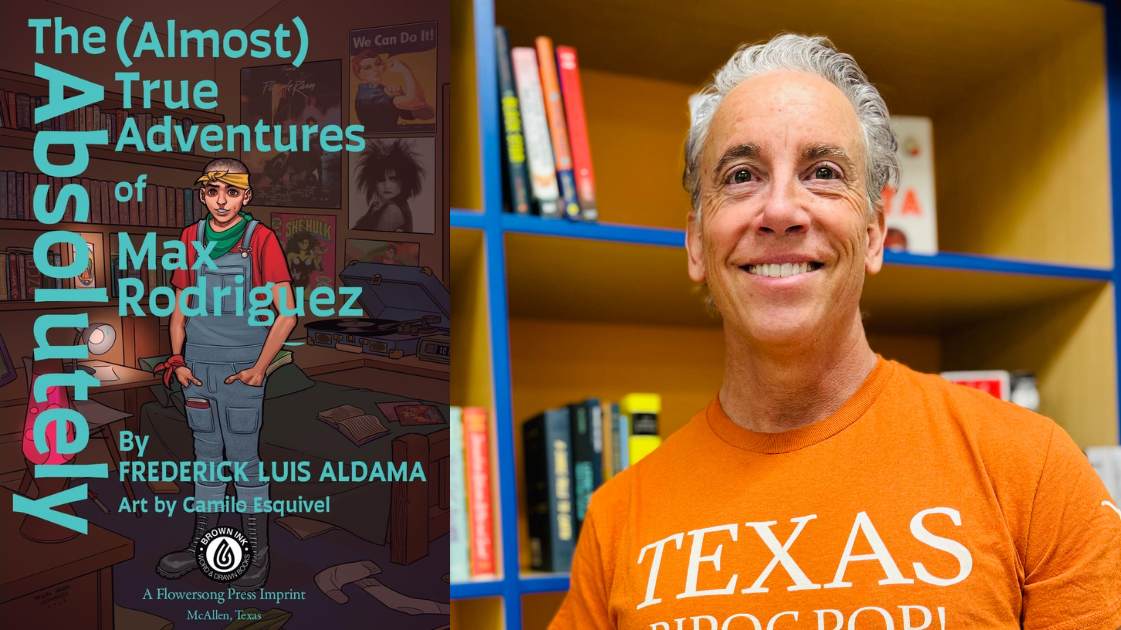

Aldama’s latest book is a young adult novel, The Absolutely (Almost) True Adventures of Max Rodriguez, published in February under the Brown Ink imprint of Flowersong Press. Illustrated by Camilo Esquivel, the “Max” of the title was born “Maxine” but they are now in ninth grade and discovering their true self. Max hangs with other “misfits” who find acceptance and freedom in each other’s company in 1990s “Nowheresville” California. Aldama tells a vibrant, hilarious, but sometimes harrowing story of self-discovery that is as authentic as it is joyous.

Aldama took time from his busy schedule to answer a few questions by email about The Absolutely (Almost) True Adventures of Max Rodriguez. His responses have been edited for length and clarity.

|

DANIEL A. OLIVAS: What—or who—inspired you to create your wonderfully well-read, self-proclaimed misfit, Max Rodriguez (née Maxine), and tell their coming-of-age story?

FREDERICK LUIS ALDAMA: I’m a sucker for coming-of-age stories—and this since I first began clocking in serious time as a teen at my school and local libraries. Happenstance, along with meeting a series of kind, generous librarians had me page-turning exquisite formation narratives bursting with imagination and belly-aching fun by the likes of Gabriel García Márquez, Salman Rushdie, Günter Grass—and yes, other rather unlikely authors, at least for me, like Lawrence Sterne, Henry Fielding, and Rabelais. But it wasn’t just any coming-of-age story that held me, keeping me butt-numbing glued to library chairs. It was those that followed characters who didn’t quite fit in that I related deeply to: Saleem Sinai with his unusual birth and bulbous cucumber nose, ditto for Tristram’s forceps-crushed nose, Oskar Matzerath’s preternatural glass shattering scream, Aurelliano III’s pig tail, to name a few. The misfits whose formation or bildung—using the more scholarly literary term—resonated deeply with my burgeoning personhood; they offered fresh, new perspectives for me to see more clearly the underbelly workings of my small slice of the world. Their journeys throw the curtains back on how society itself works to constrain and malign those who don’t fit in physically, sexually, emotionally, and cognitively to mainstream constructs and norms. Like these characters, Max reminds us that mainstream society, and its most powerful appendage, the media, gatekeep who is heard and seen, and who is allowed to relish in their respective formation journeys, as off-beat and wacky as they may be. |

When you purchase a book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission and so do independent book stores.

|

OLIVAS: Could you talk about your depiction of books as a way for “different” people to overcome obstacles?

ALDAMA: Max is born with congenital condition known as “ankyloglossia.” The flap of their tongue is too short, making it difficult if not impossible to speak. By the time the doctors figure this out and Max’s flap is snipped, and tongue loosened, Max has settled into the wondrous worlds built by authors of fiction. Max has also begun to discover answers to existential musings in their reading of great philosophical tomes. This is to say, at an early age Max has comfortably settled into their sense of self as reader, listener, and observer. This is why Max chooses not to speak for a good while after the surgery.

There are many ways to engage with our world. Like Max, as I was growing up, I found myself much more comfortable reading, listening, and observing—rather than than vocally engaging and physically interacting. At family get-togethers, I’d often tuck into corners and shadows, slowing time and stretching space to catch the tiniest nuances of expressions and interactions. Those who didn’t know me well would, at best, just write me off as shy; and, at worst, think I was aloof or that something was developmentally off about me.

Max celebrates all of us, from the wallflower-shy to those of us built physically, sexually, emotionally, and cognitively different. Max reminds us that we are not alone, both in flesh-and-blood persons and in the company of world literature’s most vital and joyously outrageous protagonists. Max celebrates all of us who perceive the world slightly askew, in thought, feeling, sight, sound, taste, touch, and scent.

OLIVAS: Max’s close friends (Miguel and Rudy) are also “misfits” who love comic books and offer each other intellectual and emotional support. What is it about comics that give these three so much sustenance?

ALDAMA: No matter how busy, overwhelmed, or exhausted, these teenagers (who dub themselves “Los Muties”) are, they always gather on Sundays to commune at the corner tienda, Mendozas. They discuss the latest superhero characters, plot twists and turns, as well as their ups and downs of life. The magic unfolds at the base of the spinrack filled with recent issue drops of X-Men, Fantastic Four, New Mutants, She-Hulk, Incredible Hulk, Spider-Man, among others.

Like many teens, Los Muties feel more comfortable sharing their feelings and experiences through something external to themselves. This could be a song, TV show, film, videogame, a novel—or, in their case, comic books. As they chew on spicey, watermelon-flavored Pica Gomas they excitedly share how Magik kicks ass with the Soulsword, for instance. They also share truths about their own individual struggles. On one occasion, for instance, Max shares the deeply contradictory feelings they experienced when learning of the existence of a half-sister, Clara. Comics are a space of shared healing for Los Muties.

Remember, too, that as much as superhero comics entertain, they also offer smart, deeply probing explorations into our existence. I don’t just gesture toward the equivalences made between the Id and Ego struggles of Hulk and those of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, for instance. There’s that, for sure. For Los Muties, Hulk, the Thing, Spidey, Rogue, Storm, Professor X, and other save-the-day outcasts and mutant superheroes model an affirmation of “otherness.”

Comics imagine a world where brown misfits like Los Muties vanquish bullies and provide safe spaces for collective learning and exploring at places like the X-Mansion. Super empowered mutants like Ororo Munroe as Storm controls the weather to subdue super villains but also to help agrarian communities grow food to eat. Storm, Ben Grimm, Spidey, Wolverine, White Tiger, Sunspot, Red Wolf, and so many others model a positive sense of belonging and proactive and progressive transforming of the world.

OLIVAS: Max’s family is a bit fractured and far from stereotypical with a grandmother who grows marijuana in her attic, an estranged Irish American grandfather, a father who comes in and out of the picture, and a ferociously independent mother who—as a teacher at an underfunded school—is often fighting the system to challenge the educational inequities her students face daily. How did you approach creating Max’s world? Did your own family members serve as inspiration?

ALDAMA: As a fellow fiction writer, you know well that there’s always little bit of us and our truths in our fiction. This includes Max, their kooky family, and wild adventures. I mention here a few of the direct inspirations from my family:

ALDAMA: Max is born with congenital condition known as “ankyloglossia.” The flap of their tongue is too short, making it difficult if not impossible to speak. By the time the doctors figure this out and Max’s flap is snipped, and tongue loosened, Max has settled into the wondrous worlds built by authors of fiction. Max has also begun to discover answers to existential musings in their reading of great philosophical tomes. This is to say, at an early age Max has comfortably settled into their sense of self as reader, listener, and observer. This is why Max chooses not to speak for a good while after the surgery.

There are many ways to engage with our world. Like Max, as I was growing up, I found myself much more comfortable reading, listening, and observing—rather than than vocally engaging and physically interacting. At family get-togethers, I’d often tuck into corners and shadows, slowing time and stretching space to catch the tiniest nuances of expressions and interactions. Those who didn’t know me well would, at best, just write me off as shy; and, at worst, think I was aloof or that something was developmentally off about me.

Max celebrates all of us, from the wallflower-shy to those of us built physically, sexually, emotionally, and cognitively different. Max reminds us that we are not alone, both in flesh-and-blood persons and in the company of world literature’s most vital and joyously outrageous protagonists. Max celebrates all of us who perceive the world slightly askew, in thought, feeling, sight, sound, taste, touch, and scent.

OLIVAS: Max’s close friends (Miguel and Rudy) are also “misfits” who love comic books and offer each other intellectual and emotional support. What is it about comics that give these three so much sustenance?

ALDAMA: No matter how busy, overwhelmed, or exhausted, these teenagers (who dub themselves “Los Muties”) are, they always gather on Sundays to commune at the corner tienda, Mendozas. They discuss the latest superhero characters, plot twists and turns, as well as their ups and downs of life. The magic unfolds at the base of the spinrack filled with recent issue drops of X-Men, Fantastic Four, New Mutants, She-Hulk, Incredible Hulk, Spider-Man, among others.

Like many teens, Los Muties feel more comfortable sharing their feelings and experiences through something external to themselves. This could be a song, TV show, film, videogame, a novel—or, in their case, comic books. As they chew on spicey, watermelon-flavored Pica Gomas they excitedly share how Magik kicks ass with the Soulsword, for instance. They also share truths about their own individual struggles. On one occasion, for instance, Max shares the deeply contradictory feelings they experienced when learning of the existence of a half-sister, Clara. Comics are a space of shared healing for Los Muties.

Remember, too, that as much as superhero comics entertain, they also offer smart, deeply probing explorations into our existence. I don’t just gesture toward the equivalences made between the Id and Ego struggles of Hulk and those of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, for instance. There’s that, for sure. For Los Muties, Hulk, the Thing, Spidey, Rogue, Storm, Professor X, and other save-the-day outcasts and mutant superheroes model an affirmation of “otherness.”

Comics imagine a world where brown misfits like Los Muties vanquish bullies and provide safe spaces for collective learning and exploring at places like the X-Mansion. Super empowered mutants like Ororo Munroe as Storm controls the weather to subdue super villains but also to help agrarian communities grow food to eat. Storm, Ben Grimm, Spidey, Wolverine, White Tiger, Sunspot, Red Wolf, and so many others model a positive sense of belonging and proactive and progressive transforming of the world.

OLIVAS: Max’s family is a bit fractured and far from stereotypical with a grandmother who grows marijuana in her attic, an estranged Irish American grandfather, a father who comes in and out of the picture, and a ferociously independent mother who—as a teacher at an underfunded school—is often fighting the system to challenge the educational inequities her students face daily. How did you approach creating Max’s world? Did your own family members serve as inspiration?

ALDAMA: As a fellow fiction writer, you know well that there’s always little bit of us and our truths in our fiction. This includes Max, their kooky family, and wild adventures. I mention here a few of the direct inspirations from my family:

An abuelita who grows pot to pay bills.

A single mamá whose handy with hammer and drill and worked as bilingual elementary teacher.

An autodidact, fair-weather papá who taught me about Darwin and Marx.

An Irish American grandpa who fancied himself cowboy à la Louis L’Amour westerns.

A taciturn, popular, smart (things came easy to him), hermano.

The list goes on. But I want us to recall here the title of the book, The Absolutely (Almost) True Adventures of Max Rodriguez. Indeed, even in the title itself is the important reminder that these are almost true adventures. That is, while we can map my biographical truths onto the novel, in the fiction-making process, there is a distillation and reconstruction of those building blocks of reality.

I share here with you what I tell my students again and again: Fiction is not a mirror reflection of reality, per Stendhal’s famous mirror-in-the-road analogy. Nor is fiction a copy, imitation, or simulacrum of anything in the real world. The building blocks of fiction, no matter how fantastic and strange, are always drawn from the real world, but fiction is not reality. Just as a map is not the territory.

And so, while Max Rodriguez is intimately connected to reality in that its characters, things, and settings, say, refer to people, things, and places we recognize, it is ultimately a re-created reality. It is something new that adds to the world—and not something that tries to replicate one-to-one what already exists in the world. And this is its power.

Max Rodriguez opens us to the creative space of the co-created daydream, the forward-looking, wish-fulfilment brain that creates new worlds and new worldviews, where it’s possible to imagine an empowered and emancipated misfit capable of acting, engaging, and exploring in a world that constantly seeks to crush and control non-normative thoughts, feelings, and actions. And this is why Max Rodriguez ends with Max putting pen to paper create their own fiction—and declaring that “like all others of my misfit kind, there’s still much adventuring for me to get to know the world, and me in it, just a little more.”

OLIVAS: Speaking of which, there’s Camilo Esquivel’s stunning spot illustration at the end of the novel with Max ready to write, balancing a giant-sized pencil balanced on their shoulder. Could you talk about your collaboration with Camilo Esquivel who illustrated your novel?

ALDAMA: Yes, that last spot illustration’s so powerful. We really feel the weight and joy of the so-called power of the pen. As far as Camilo coming on as the artist, all I can say is that serendipity was certainly smiling my way. Years ago, I met his brother, Felipe. His animation studio did the cartoon version of my children’s book, The Adventures of Chupacabra Charlie. While the animated short, Carlitos Chupacabra, was making its international tour of film fests that included Cannes, I began writing Max Rodriguez. I mentioned in passing to Felipe the novel and that I wanted to include spot illustrations—drawn from a teen perspective and that could stand alone as pieces of art in, say, an exhibition. He mentioned that his brother Camilo was an artist. Intros were made, portfolios were shared, and the rest is history.

Camilo worked hard to achieve that perfect balance between teen drawing and stand-alone art piece. You can see from the pencil sketches I decided to include at the end of the novel Camilo’s move from more realist to a more abstract aesthetic. His strong lines and direct yet slightly abstract style worked perfectly for what I envisioned for the novel. And, of course, his at once subdued and vibrant color palette beautifully conveys moments of struggle, seriousness, and joy in Max’s coming-of-age adventures.

I share here with you what I tell my students again and again: Fiction is not a mirror reflection of reality, per Stendhal’s famous mirror-in-the-road analogy. Nor is fiction a copy, imitation, or simulacrum of anything in the real world. The building blocks of fiction, no matter how fantastic and strange, are always drawn from the real world, but fiction is not reality. Just as a map is not the territory.

And so, while Max Rodriguez is intimately connected to reality in that its characters, things, and settings, say, refer to people, things, and places we recognize, it is ultimately a re-created reality. It is something new that adds to the world—and not something that tries to replicate one-to-one what already exists in the world. And this is its power.

Max Rodriguez opens us to the creative space of the co-created daydream, the forward-looking, wish-fulfilment brain that creates new worlds and new worldviews, where it’s possible to imagine an empowered and emancipated misfit capable of acting, engaging, and exploring in a world that constantly seeks to crush and control non-normative thoughts, feelings, and actions. And this is why Max Rodriguez ends with Max putting pen to paper create their own fiction—and declaring that “like all others of my misfit kind, there’s still much adventuring for me to get to know the world, and me in it, just a little more.”

OLIVAS: Speaking of which, there’s Camilo Esquivel’s stunning spot illustration at the end of the novel with Max ready to write, balancing a giant-sized pencil balanced on their shoulder. Could you talk about your collaboration with Camilo Esquivel who illustrated your novel?

ALDAMA: Yes, that last spot illustration’s so powerful. We really feel the weight and joy of the so-called power of the pen. As far as Camilo coming on as the artist, all I can say is that serendipity was certainly smiling my way. Years ago, I met his brother, Felipe. His animation studio did the cartoon version of my children’s book, The Adventures of Chupacabra Charlie. While the animated short, Carlitos Chupacabra, was making its international tour of film fests that included Cannes, I began writing Max Rodriguez. I mentioned in passing to Felipe the novel and that I wanted to include spot illustrations—drawn from a teen perspective and that could stand alone as pieces of art in, say, an exhibition. He mentioned that his brother Camilo was an artist. Intros were made, portfolios were shared, and the rest is history.

Camilo worked hard to achieve that perfect balance between teen drawing and stand-alone art piece. You can see from the pencil sketches I decided to include at the end of the novel Camilo’s move from more realist to a more abstract aesthetic. His strong lines and direct yet slightly abstract style worked perfectly for what I envisioned for the novel. And, of course, his at once subdued and vibrant color palette beautifully conveys moments of struggle, seriousness, and joy in Max’s coming-of-age adventures.

Comment Box is loading comments...

|

|