Desire, Cruelty, and Language as a “Beautiful Monster”: Mónica Ojeda on Nefando

|

When you purchase a book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission and so do independent book stores.

|

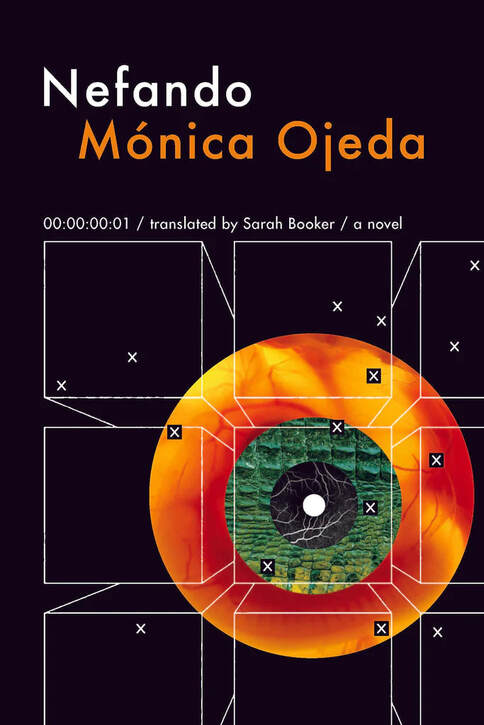

Following the success of last year’s National Book Award–nominated Jawbone, a chilling English-language debut drawing from Lovecraftian horror in its portrayal of the dynamics in an all-girls’ Catholic high school, Ecuadorian novelist and poet Mónica Ojeda returns this week with the English translation of Nefando, a slim but exceptional work that traverses many of the themes and obsessions that have come to characterize Ojeda’s oeuvre—the twisted connections between desire and fear, the blurred line separating victims from perpetrators, the dangers of burgeoning sexuality—but sets them in the context of the digital world of the Deep Web and all the horrors it hides.

The book focuses on six artists sharing an apartment in Barcelona: Kiki, a twenty-three-year-old writer in the process of penning a pornographic novel about children; Ivan, a master’s student struggling to contain the violent impulses arising from his ambivalent relationship with his body; El Cuco, a hacker, video game designer, and member of the demoscene; and Irene, Emilio, and María Cecilia Terán, the enigmatic siblings whose motivation for and creation of the online horror game Nefando constitutes the axis upon which the novel revolves. Featuring such a varied cast of characters, Nefando is profusely multivocal, alternating first-person accounts with interviews about the creation of the game with chapters of Kiki’s pornovela, its speakers moving between Mexican, Ecuadorian, or Catalan slang depending on their nationality. As it veers from prose to code, from community forums to hand-drawn images, the novel is continuously pushing the boundaries of language and form in its exploration of how to give speech to the unspeakable. It is a complex and profoundly affecting novel, one that perfectly displays the verve and technical proficiency that have made its author one of the most exciting Latin American writers working today. |

In anticipation of the book’s release this week, Ojeda kindly agreed to answer a few questions for Latino Book Review about Nefando and the process of writing the novel and revisiting it for its English translation.

ISABELLA PILOTTA GOIS: Nefando was written in early 2014, almost a decade ago. It was first published by Candaya in 2016, and you have revisited the novel throughout the years as it was published in countries like Bolivia, Mexico, and now the United States. Can you talk about how your relationship with the novel has changed (or remained the same) over the years?

MÓNICA OJEDA: When I look back, I still don’t completely understand what was my state of mind when I wrote Nefando. It is a very dark book that narrates harsh experiences like sexual abuse, a book that thinks about desire, pain, and cruelty all together, as if they were the same monster. I must say that I’m a little afraid of it, a little afraid of my own book. I haven’t read it since it got published in Spanish in 2016.

PILOTTA GOIS: This novel is your second collaboration with translator Sarah Booker after Jawbone, which was published last year. Did the experience of working together on Nefando differ from that of Jawbone? If so, in what way?

OJEDA: Sarah is great. I don’t have much to say about her process because I don’t get very much involved. It was the same with Jawbone and Nefando. My English is not that good, but I also like to detach from my works and let the translators work as freely as possible. Sarah always writes to me while she is translating and asks me brilliant questions because she likes to do the job well. I try to answer as best I can.

PILOTTA GOIS: The Terán siblings are enigmatic figures in the novel, both for the other characters and for the reader, as their actions routinely challenge socially accepted narratives about how survivors of abuse “should” act or behave. Can you talk a little about the process of creating these three characters? How did you navigate writing their distinct relationships with victimhood and trauma?

OJEDA: They are shocking characters because they react to their own abuse in a way that is very unsettling to others. People expect a very specific narrative of pain from victims, but these siblings resist it. They’ve been harmed—you can see that especially in María Cecilia—but they want to do with their experience something that breathes in the limit of ethical behavior. I think they are very complex characters, and in the novel, they are more than just victims: they do something creative and dark with what was done to them, something some people would perceive as evil.

PILOTTA GOIS: That was a big part of what made them so interesting to read—the siblings seem uninterested in fitting into not only the other characters’ clichéd ideas about survivors of sexual abuse, but also the reader’s. They’re not concerned with being “legible” to others. Can you talk about the research process that went into writing these characters?

OJEDA: I remember that while I was writing I read The Body in Pain by Elaine Scarry, some essays about cruelty and violence, testimonies of people that have suffered sexual abuse, etc. But at the end when you create characters it is more about trying to imagine how a human being can react to something very specific, and there are no formulas if you really want to explore the big scale of human emotions and experiences.

PILOTTA GOIS: Even though the novel revolves largely around the siblings, we only hear directly from each of them once, in their respective chapters. Everything else we discover about them is relayed to us by the other characters. Was this always the case when you were writing the novel? Why?

OJEDA: Yes, because I wanted them to be known from a distance. I didn’t want to do a detailed portrait of them, but rather write them as some kind of myth: near and far at the same time, known and unknown. There are characters that should have a mysterious aura to be alive. I think that all characters need that, more or less, to be alive and not become statues, but the Terán siblings especially because to others they are difficult to understand. I also wanted my readers to be a little afraid of them. Disturbed by them, just like the other characters are in the novel.

PILOTTA GOIS: You mentioned María Cecilia earlier, whose chapter is one of my favorites, because it underlines this idea that the novel and the characters themselves are constantly returning to—how to talk about those wounds for which there are no words. Did you always know that there was going to be a part of the book that was purely visual?

OJEDA: No, I decided that María Cecilia’s chapter was going to be all drawings when I was almost about to finish. For me, writing is very much like an exploration, so I don’t really know what I’m going to find or do when I start. I have some ideas, some intuitions, and I work with them in a very fluid way. So when I got to María Cecilia’s chapter and I had to write it, I just knew by then that she would not have words to make sense of her own experience. That’s why she is the one who shows the most harm out of the siblings: because she can’t articulate her own pain, she is unable to make a story of it. She is still in that place where horror and violence cut your tongue and take away your language. By the end of the process of writing Nefando, it was very clear to me that it was a novel about language as a beautiful monster.

PILOTTA GOIS: Speaking of language, your prose in the book is gorgeously dense, lush with metaphors that often combine images of natural landscapes, animals, and the human body. How did you go about crafting your voice as a writer?

OJEDA: For me, language is not just an instrument to effectively tell a story, it is the way I think. My prose is pure thought, and I tend to think in a poetic way because I read a lot of poetry. I remember that Joseph Conrad once said: “The power of sound has always been greater than the power of sense.” So for me, sound, rhythm, metaphors, and powerful images are not an attrezzo, they are the novel. It’s like saying that rhythm and sound are the attrezzo of a song—no: they are the song. I have worked a lot on my prose, on my music, and I’m still doing it. It never ends.

PILOTTA GOIS: How did you approach writing the sections in the novel that are from a child’s POV? I’m thinking about Irene’s chapter, but also about Diego, Eduardo, and Nella in Kiki’s pornovela, and about El Cuco sharing that Irene once spoke to him about “the image of childhood she saw as a cultural representation that had nothing to do with the real thing.”

OJEDA: People usually don’t like to talk about children’s violence, or sexual desires, or cruelty, because that is not the image we want to have of them. We want to think that kids are just innocent and pure creatures, that sexuality only happens in our teenage years. That’s not the truth. Freud used to refer to children as polymorphous perverts for a reason. We know, because we have seen it, how much cruelty and desire a child can hold. I think we usually become better people when we grow up because we learn to amplify our empathy. When we are kids, it is all about ourselves, and we can be really cruel to others. Having said this, I admire how strong kids are; they are much stronger than adults give them credit for. That POV was very interesting to me in the process of writing the novel: a strong and very ductile perspective.

PILOTTA GOIS: Iván, one of the characters sharing an apartment with the Terán siblings, has a complicated and violent relationship with his own body. Why did you choose to draw from Aztec religious imagery to articulate this conflict?

OJEDA: Iván is Mexican and, like you say, has a very difficult relationship with his body. He is divided and his desires are violent and destructive. Sometimes he sees his own internal battle as the one incarnated in Quetzalcoatl, the feathered snake, a god that represents the light and knowledge, but also the earthly things. Tezcatlipoca is his opposite, his destructive force. He seems to have a war inside himself that is ancient. I love how myths are very much alive inside of us; we think of them as only stories that we tell ourselves to explain what we can’t explain directly, but they are so much more: they are a poetic way of relating to the invisible. They are poetry.

PILOTTA GOIS: Can you talk about the link between the violence that Iván inflicts on himself and the violence that he inflicts on others? What were you looking to explore in the scenes with his ex-girlfriend and the dog near the end of the novel?

OJEDA: Nefando is a novel about how we can be damaged by others’ desires, but also about how we can damage others with our desires. It is a novel that explores how we can be victims and, a second later, aggressors. We are potentially both. Iván hurts himself because he has a conflict with his identity that surpasses his maturity to confront it. He hurts others because he is full of rage, but that rage is just a mask. Underneath it is pain.

PILOTTA GOIS: There’s a chapter where several gamers who played Nefando (the video game) describe their experiences in a community forum, and the reader discovers all these very specific details about a game that we ourselves never get to see nor play. Can you tell me about the process of coming up with the video game—its aesthetics, its symbols, the various options and choices that were provided to the users? Did you research any particular video games or forums to create the fictional Nefando?

OJEDA: Yes, I read a lot of gamers forums and played a lot of online video games. One of the things that I love about writing is that it gets me into investigating and studying things that, sometimes, I have never been interested in before. I love video games, I play a lot on my PS4, but I didn’t know about secret online video games or underground video games, the creepy ones. I discovered them by navigating the internet, so I used that experience, but also my own imagination.

I wanted Nefando, the game, to be poetic and sordid and scary, but not in an obvious way. The room, as a metaphor, appears along the novel because many chapters are called by a room number. A room is a very intimate space, and you can find all sorts of beautiful and horrific things inside one. That’s why I made it that, in the game, you never leave the room. Everything happens between those four walls.

PILOTTA GOIS: In recent years, publishing houses based in the US have published translations of works by Mariana Enríquez, Fernanda Melchor, and Alejandro Zambra, among others. What are some other Latin American writers that you would like to see read, or translated to English?

OJEDA: Yuliana Ortiz is an amazing writer; she is a novelist and a poet. Also, I would love to see María Auxiliadora Balladares’s poetry translated, and Marina Closs’s short stories.

Nefando is out now from Coffee House Press.

Click here to read our review of Mónica Ojeda’s short story collection Las voladoras.

ISABELLA PILOTTA GOIS: Nefando was written in early 2014, almost a decade ago. It was first published by Candaya in 2016, and you have revisited the novel throughout the years as it was published in countries like Bolivia, Mexico, and now the United States. Can you talk about how your relationship with the novel has changed (or remained the same) over the years?

MÓNICA OJEDA: When I look back, I still don’t completely understand what was my state of mind when I wrote Nefando. It is a very dark book that narrates harsh experiences like sexual abuse, a book that thinks about desire, pain, and cruelty all together, as if they were the same monster. I must say that I’m a little afraid of it, a little afraid of my own book. I haven’t read it since it got published in Spanish in 2016.

PILOTTA GOIS: This novel is your second collaboration with translator Sarah Booker after Jawbone, which was published last year. Did the experience of working together on Nefando differ from that of Jawbone? If so, in what way?

OJEDA: Sarah is great. I don’t have much to say about her process because I don’t get very much involved. It was the same with Jawbone and Nefando. My English is not that good, but I also like to detach from my works and let the translators work as freely as possible. Sarah always writes to me while she is translating and asks me brilliant questions because she likes to do the job well. I try to answer as best I can.

PILOTTA GOIS: The Terán siblings are enigmatic figures in the novel, both for the other characters and for the reader, as their actions routinely challenge socially accepted narratives about how survivors of abuse “should” act or behave. Can you talk a little about the process of creating these three characters? How did you navigate writing their distinct relationships with victimhood and trauma?

OJEDA: They are shocking characters because they react to their own abuse in a way that is very unsettling to others. People expect a very specific narrative of pain from victims, but these siblings resist it. They’ve been harmed—you can see that especially in María Cecilia—but they want to do with their experience something that breathes in the limit of ethical behavior. I think they are very complex characters, and in the novel, they are more than just victims: they do something creative and dark with what was done to them, something some people would perceive as evil.

PILOTTA GOIS: That was a big part of what made them so interesting to read—the siblings seem uninterested in fitting into not only the other characters’ clichéd ideas about survivors of sexual abuse, but also the reader’s. They’re not concerned with being “legible” to others. Can you talk about the research process that went into writing these characters?

OJEDA: I remember that while I was writing I read The Body in Pain by Elaine Scarry, some essays about cruelty and violence, testimonies of people that have suffered sexual abuse, etc. But at the end when you create characters it is more about trying to imagine how a human being can react to something very specific, and there are no formulas if you really want to explore the big scale of human emotions and experiences.

PILOTTA GOIS: Even though the novel revolves largely around the siblings, we only hear directly from each of them once, in their respective chapters. Everything else we discover about them is relayed to us by the other characters. Was this always the case when you were writing the novel? Why?

OJEDA: Yes, because I wanted them to be known from a distance. I didn’t want to do a detailed portrait of them, but rather write them as some kind of myth: near and far at the same time, known and unknown. There are characters that should have a mysterious aura to be alive. I think that all characters need that, more or less, to be alive and not become statues, but the Terán siblings especially because to others they are difficult to understand. I also wanted my readers to be a little afraid of them. Disturbed by them, just like the other characters are in the novel.

PILOTTA GOIS: You mentioned María Cecilia earlier, whose chapter is one of my favorites, because it underlines this idea that the novel and the characters themselves are constantly returning to—how to talk about those wounds for which there are no words. Did you always know that there was going to be a part of the book that was purely visual?

OJEDA: No, I decided that María Cecilia’s chapter was going to be all drawings when I was almost about to finish. For me, writing is very much like an exploration, so I don’t really know what I’m going to find or do when I start. I have some ideas, some intuitions, and I work with them in a very fluid way. So when I got to María Cecilia’s chapter and I had to write it, I just knew by then that she would not have words to make sense of her own experience. That’s why she is the one who shows the most harm out of the siblings: because she can’t articulate her own pain, she is unable to make a story of it. She is still in that place where horror and violence cut your tongue and take away your language. By the end of the process of writing Nefando, it was very clear to me that it was a novel about language as a beautiful monster.

PILOTTA GOIS: Speaking of language, your prose in the book is gorgeously dense, lush with metaphors that often combine images of natural landscapes, animals, and the human body. How did you go about crafting your voice as a writer?

OJEDA: For me, language is not just an instrument to effectively tell a story, it is the way I think. My prose is pure thought, and I tend to think in a poetic way because I read a lot of poetry. I remember that Joseph Conrad once said: “The power of sound has always been greater than the power of sense.” So for me, sound, rhythm, metaphors, and powerful images are not an attrezzo, they are the novel. It’s like saying that rhythm and sound are the attrezzo of a song—no: they are the song. I have worked a lot on my prose, on my music, and I’m still doing it. It never ends.

PILOTTA GOIS: How did you approach writing the sections in the novel that are from a child’s POV? I’m thinking about Irene’s chapter, but also about Diego, Eduardo, and Nella in Kiki’s pornovela, and about El Cuco sharing that Irene once spoke to him about “the image of childhood she saw as a cultural representation that had nothing to do with the real thing.”

OJEDA: People usually don’t like to talk about children’s violence, or sexual desires, or cruelty, because that is not the image we want to have of them. We want to think that kids are just innocent and pure creatures, that sexuality only happens in our teenage years. That’s not the truth. Freud used to refer to children as polymorphous perverts for a reason. We know, because we have seen it, how much cruelty and desire a child can hold. I think we usually become better people when we grow up because we learn to amplify our empathy. When we are kids, it is all about ourselves, and we can be really cruel to others. Having said this, I admire how strong kids are; they are much stronger than adults give them credit for. That POV was very interesting to me in the process of writing the novel: a strong and very ductile perspective.

PILOTTA GOIS: Iván, one of the characters sharing an apartment with the Terán siblings, has a complicated and violent relationship with his own body. Why did you choose to draw from Aztec religious imagery to articulate this conflict?

OJEDA: Iván is Mexican and, like you say, has a very difficult relationship with his body. He is divided and his desires are violent and destructive. Sometimes he sees his own internal battle as the one incarnated in Quetzalcoatl, the feathered snake, a god that represents the light and knowledge, but also the earthly things. Tezcatlipoca is his opposite, his destructive force. He seems to have a war inside himself that is ancient. I love how myths are very much alive inside of us; we think of them as only stories that we tell ourselves to explain what we can’t explain directly, but they are so much more: they are a poetic way of relating to the invisible. They are poetry.

PILOTTA GOIS: Can you talk about the link between the violence that Iván inflicts on himself and the violence that he inflicts on others? What were you looking to explore in the scenes with his ex-girlfriend and the dog near the end of the novel?

OJEDA: Nefando is a novel about how we can be damaged by others’ desires, but also about how we can damage others with our desires. It is a novel that explores how we can be victims and, a second later, aggressors. We are potentially both. Iván hurts himself because he has a conflict with his identity that surpasses his maturity to confront it. He hurts others because he is full of rage, but that rage is just a mask. Underneath it is pain.

PILOTTA GOIS: There’s a chapter where several gamers who played Nefando (the video game) describe their experiences in a community forum, and the reader discovers all these very specific details about a game that we ourselves never get to see nor play. Can you tell me about the process of coming up with the video game—its aesthetics, its symbols, the various options and choices that were provided to the users? Did you research any particular video games or forums to create the fictional Nefando?

OJEDA: Yes, I read a lot of gamers forums and played a lot of online video games. One of the things that I love about writing is that it gets me into investigating and studying things that, sometimes, I have never been interested in before. I love video games, I play a lot on my PS4, but I didn’t know about secret online video games or underground video games, the creepy ones. I discovered them by navigating the internet, so I used that experience, but also my own imagination.

I wanted Nefando, the game, to be poetic and sordid and scary, but not in an obvious way. The room, as a metaphor, appears along the novel because many chapters are called by a room number. A room is a very intimate space, and you can find all sorts of beautiful and horrific things inside one. That’s why I made it that, in the game, you never leave the room. Everything happens between those four walls.

PILOTTA GOIS: In recent years, publishing houses based in the US have published translations of works by Mariana Enríquez, Fernanda Melchor, and Alejandro Zambra, among others. What are some other Latin American writers that you would like to see read, or translated to English?

OJEDA: Yuliana Ortiz is an amazing writer; she is a novelist and a poet. Also, I would love to see María Auxiliadora Balladares’s poetry translated, and Marina Closs’s short stories.

Nefando is out now from Coffee House Press.

Click here to read our review of Mónica Ojeda’s short story collection Las voladoras.

|

Comment Box is loading comments...

|

|