“Consciencia” is not about “I” but “we”

Interview with Cherríe Moraga

Photo by Marcos Colón

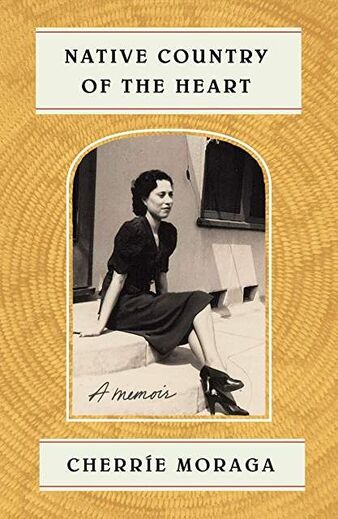

Cherríe Moraga (1952-present) is a Chicana writer, feminist advocate, poet, essayist, playwright, and cultural activist. Daughter of a Mexican American mother and an Anglo-American father, she was raised in southern California in the days when the civil rights, gender and social movements were gaining importance. Her work focuses on expressions of identity, ethnic nationalism, sexuality, Chicana feminist thought, indigeneity, and social justice. She is known for her influential publication, co-edited with Gloria E. Anzaldúa, This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981), and most recently, Native Country of the Heart: A Memoir (2019). She is now a Professor in the Department of English at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where she has instituted, with visual artist, Celia Herrera Rodríguez, Las Maestra Center for Xicana Indigenous Thought, Art and Social Practice. In this interview, she discusses her trajectory as a Chicana writer and how her work exemplifies the intersectionality of the U.S. women of color movement. As a teacher and writer, she describes the goals she sets forth for her student writers, especially first generation Latinx students, and the ways in which her own writings might model the way poetry can best be achieved through an embodied visceral process. Speaking from the intimate to the global, she locates the importance of ‘going home’ (cultivating "consciencia" of one's origin and origin story) as key to authentic critical engagement with the world. The interview took place in June, in Davis, California, during the Thirteenth Biennial Conference of the Association for the Study of Literature and Environment (ASLE) where Cherríe Moraga was one the keynote speakers.

MARCOS COLÓN: Your work has received increasing attention for its notions of identity and consciousness. I'd like to begin by asking how has your work developed over the years and what are the main social or political issues that you consider today?

CHERRÍE MORAGA: That’s a huge question. I’ve been writing for many, many years, over forty years, so in that sense, there are different writing epochs that one has. As a young writer it was a very different time because I was coming of age during the period of the movimiento chicano in the 1970s. There were a lot of sites of silences in that movement. At the time, I was beginning to question aloud what it means to be a woman in this world, and specifically a chicana, a Mexican-American in the United States. But I also was beginning to make connections around other more censured identity questions, specifically around lesbian and queer identities. In academic circles today, this is called “intersectionality,’ but in the late 1970s, during the making of This Bridge Called My Back we, as women of color, referred to this kind of connective tissue of oppression and liberation simply as “theory in the flesh.” I see now that “theory in the flesh” served as a precursor to recognizing embodied practices as a knowledge base: the idea that somehow within our bodies, if we’re paying attention and if we listen to our hearts and our intuition, we will see where the silences are and we will see where ignorances are. And from there we construct a living politic.

In those early years, we were really trying to broach the very forbidden subjects that other liberation movements of the 60s and 70s overlooked. After Bridge, I began to look more and more at the specificity of what it is to be chicana and the history of colonization particular to the chicanx experience. One of the most powerful and I think beautiful things about el movimiento was that while it claimed us as mestizo peoples, it also acknowledged us as, at least in part, Indigenous Americans. That alone, but along with our collective origin story of Aztlán, absolutely radicalized me. As Mexicans, we remembered that the U.S. southwest, was once México, but it was and is also indigenous land. What we didn’t know was that hundreds of years before the arrival of the Spanish, the Mexicas (or Aztecs) had migrated from that region to eventually land in Tenochtitlan, present day Mexico City. So, there was a story — part history, part myth — that symbolically (for we are not all Mexica) put Indigenous ground under our feet as Chicanos in the U.S.

Cherríe Moraga (1952-present) is a Chicana writer, feminist advocate, poet, essayist, playwright, and cultural activist. Daughter of a Mexican American mother and an Anglo-American father, she was raised in southern California in the days when the civil rights, gender and social movements were gaining importance. Her work focuses on expressions of identity, ethnic nationalism, sexuality, Chicana feminist thought, indigeneity, and social justice. She is known for her influential publication, co-edited with Gloria E. Anzaldúa, This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981), and most recently, Native Country of the Heart: A Memoir (2019). She is now a Professor in the Department of English at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where she has instituted, with visual artist, Celia Herrera Rodríguez, Las Maestra Center for Xicana Indigenous Thought, Art and Social Practice. In this interview, she discusses her trajectory as a Chicana writer and how her work exemplifies the intersectionality of the U.S. women of color movement. As a teacher and writer, she describes the goals she sets forth for her student writers, especially first generation Latinx students, and the ways in which her own writings might model the way poetry can best be achieved through an embodied visceral process. Speaking from the intimate to the global, she locates the importance of ‘going home’ (cultivating "consciencia" of one's origin and origin story) as key to authentic critical engagement with the world. The interview took place in June, in Davis, California, during the Thirteenth Biennial Conference of the Association for the Study of Literature and Environment (ASLE) where Cherríe Moraga was one the keynote speakers.

MARCOS COLÓN: Your work has received increasing attention for its notions of identity and consciousness. I'd like to begin by asking how has your work developed over the years and what are the main social or political issues that you consider today?

CHERRÍE MORAGA: That’s a huge question. I’ve been writing for many, many years, over forty years, so in that sense, there are different writing epochs that one has. As a young writer it was a very different time because I was coming of age during the period of the movimiento chicano in the 1970s. There were a lot of sites of silences in that movement. At the time, I was beginning to question aloud what it means to be a woman in this world, and specifically a chicana, a Mexican-American in the United States. But I also was beginning to make connections around other more censured identity questions, specifically around lesbian and queer identities. In academic circles today, this is called “intersectionality,’ but in the late 1970s, during the making of This Bridge Called My Back we, as women of color, referred to this kind of connective tissue of oppression and liberation simply as “theory in the flesh.” I see now that “theory in the flesh” served as a precursor to recognizing embodied practices as a knowledge base: the idea that somehow within our bodies, if we’re paying attention and if we listen to our hearts and our intuition, we will see where the silences are and we will see where ignorances are. And from there we construct a living politic.

In those early years, we were really trying to broach the very forbidden subjects that other liberation movements of the 60s and 70s overlooked. After Bridge, I began to look more and more at the specificity of what it is to be chicana and the history of colonization particular to the chicanx experience. One of the most powerful and I think beautiful things about el movimiento was that while it claimed us as mestizo peoples, it also acknowledged us as, at least in part, Indigenous Americans. That alone, but along with our collective origin story of Aztlán, absolutely radicalized me. As Mexicans, we remembered that the U.S. southwest, was once México, but it was and is also indigenous land. What we didn’t know was that hundreds of years before the arrival of the Spanish, the Mexicas (or Aztecs) had migrated from that region to eventually land in Tenochtitlan, present day Mexico City. So, there was a story — part history, part myth — that symbolically (for we are not all Mexica) put Indigenous ground under our feet as Chicanos in the U.S.

|

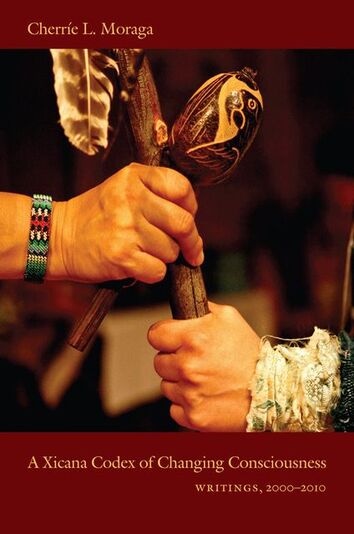

Since those early 1980 writings, my work has evolved from poet-essayist to playwright and memoirist, but I think that the concept or belief that has illuminated my writer’s road more than anything so far is that: as people of color, as people forced into migration, as Indigenous and mestizo peoples, we have a “right to remember.” This came to me writing an essay, “Indígena as Scribe,” for what would become the 2010 collection, A Xicana Codex of Changing Consciousness. In part, it was a kind of manifesto declaring that as Chicanx peoples, it is our right to remember — that is, we have the R-I-G-H-T to remember; and, we make rite--R-I-T-E--to remember; and, finally we write — (W)R-I-T-E to remember.

For me, overall, I can say that this is my work, as a writer and teacher, to help my students ‘go home’ in this way, to believe they have a right and responsibility to their origin stories — especially raza, especially Indigenous and students of color who are mostly told by the university to forget. When they ‘go home’ in their critical thinking, shifting their perspective even a smallest bit away from the dominating narratives of Western Thought, they begin to question their own colonization. The key is understanding that colonization is linked to recognizing how, for many of us as mestizo peoples, we became de-indigenized. Those questions continue to perplex me, continue to challenge me, and that's what my work in recent years, more than anything else, examines. |

For example, the first impulse for my latest book, Native Country of the Heart, arose from my mother's journey with Alzheimer’s. Her loss of memory and my intimate relationship with her during that time, took me literally and literarily ‘back home,’ where I was forced to confront multiple sites of amnesia, including my own girlhood growing up two blocks from the San Gabriel Mission and its history of Native genocide; as well as larger questions of cultural amnesia as mexicanos in the United States

|

COLÓN: This leads me to my next question: Along with what you have already spoken of in terms of helping your students and readers come to a certain politicized consciencia, what else do you want your students, in particular, to gain from your teachings and writings?

MORAGA: Last year I taught a class called Floricanto (Flower and Song) — In Xochitl, In Cuicatl -- the Nahuatl expression for poetry. I designed the course as a poetry reading and writing class, which was a bit of a challenge, in that I had two hundred students. It took place in a big lecture hall, but I tried to make the class as intimate as possible, by intimating my own world to them. So, this one time, I remember, I said to them. . . “Okay, I’m in my mid- sixties. I can count and possibly conjecture how much time, if I’m lucky, I got left in my own life. And most of you are in your early twenties. Forty-plus years ago, the world was so different. Today, the urgency about what you all will witness (and I will not) in terms of changes in the environment lays heavy on my heart.” My hopes and fears for the planet, the natural world, have been top on my list of concerns for many, many years. But, of course, every year becomes more urgent. As every year climate change accelerates and every year I grow older. I continue . . .

“You’re still young. Most of you don't have children yet, but what will your children see? This is the world I’m leaving you with, and with my deepest apologies.” But then I ask myself, who am I apologizing for, except Corporate American Greed?

|

This is the urgency of the times and we need to do this, at each and every opportunity with young folk. We must speak personally about time running out. We cannot afford to be generic. Our approach to questions of the environment, like everything we believe in, has to be very culturally specific. If you're talking to or teaching young Latinx students you have to ask them questions like: How are you going to save this planet? What are the values that you learned culturally, but may have forgotten, that could serve as the basis for a more harmonious relationship with the natural world? What do you know about ways of making extended familia and working cooperatively that could be of use? How does your spirit practice support an ecosystem of mutual respect among sentient beings? Are your values distinct from competition and capitalist motives? If so, how? Were you brought up to honor individualism over common good or the other way around?

This nation-state privileges competition over cooperation, always looking to the future, future, future, but never looking back to find out how perhaps the most effective strategies for survival could be found in our origin stories and our ancestral traditions. This means something quite significant to me because I teach such questions through the Arts. I feel like if I can get people to write their narratives, their stories, that it opens up the possibility for consciencia, and consciencia then is going to take them to that place of seeing themselves as members of not only their own cultura but also members of this planet. They're young so it's a hard-sell because they are eager to look ahead to the promise of their future. But, from the perspective of climate change, it doesn’t look too promising, except in the great promise of what might arise in them as resistance.

I think, for me, particularly working with first-generation young Latinx students that they have really been taught the survival notion of the American Dream. Their parents are saying, “Mijo, mija, get an education and make yourself the money.” They are being asked to see the world as a progressive plotline from ‘not having’ to ‘having’. But beneath it all, they are also receiving a deeper message, which is to be “responsible” to something greater than a career: to their family, their community and ultimately to their planet. If they can draw that connection from home values to world values, they could become especially emboldened warriors in the world that's in front of them. But to counter those narratives of the American Dream is really, really hard.

COLÓN: You mentioned earlier the concept of cultural amnesia and this obliviousness that we live in and how you are mirroring your mother's experience of memory loss with what we are witnessing today. Is the main contribution of your work to make us more aware of our identity and our origins? How does consciousness fit into this?

MORAGA: Well, yes, I just feel like, I’ve been writing about cultural loss since my collection of writings, The Last Generation; that is, at least since 1992. It was the Quincentenary, 500 years since Columbus. It was a really key moment for me where, the idea of decolonial thinking was leaving academia and just beginning to hit a broader base as a public conversation. But for me I couldn't think about decolonization without deindianization. How do you break something down (deconstruct it), without seeing what was there before its construction? If we look at América, what came before was indígena.

When I look at all the centroamericanos en los caravanas, coming in, arriving at la frontera, they are mostly Indigenous people, but everybody is being told to identify with their nation state. I’m supposed to just say, “I'm an American,” and they're supposed to say they're Guatemalan or Honduran or Salvadoran. But the fact of the matter is that one of the most progressive ways to counter the terror and displacement caused by the greed and corruption of our respective nation-states, is to recognize and affirm that we are also part of a pueblo, that we have an origin story, and that that origin story for us as people, as mestizos in the United States, and as indigenous people, helps us understand that we were de-indianized strategically. I think that it reflects a critical moment of consciencia when you, as a teacher, tell someone this and they can recognize that historical moment in their own story. This is so evident in many of my students where some of them are just one generation away from speaking Zapotec. In their bodies and through their presence in this country, the U.S. is being re-Indianized. I see in their faces how the world as they thought they knew it just took a giant flip and the mirror is pointed in their direction. They tell me with their eyes — “Are you crazy? Look at you, you're a professor, you've got all this good going for you. You are the living breathing American Dream. And you're asking me to go back to my origins?” And I answer, “Absolutely.” They do not have to choose spiritual poverty to no longer be poor. And they do not have to be alone in this. There's a movimiento de consciencia that's developing. “Consciencia” is not about “I” but “we.” There's power in that moment of discovery. Ironically, it was what they learned at home in the first place.

This nation-state privileges competition over cooperation, always looking to the future, future, future, but never looking back to find out how perhaps the most effective strategies for survival could be found in our origin stories and our ancestral traditions. This means something quite significant to me because I teach such questions through the Arts. I feel like if I can get people to write their narratives, their stories, that it opens up the possibility for consciencia, and consciencia then is going to take them to that place of seeing themselves as members of not only their own cultura but also members of this planet. They're young so it's a hard-sell because they are eager to look ahead to the promise of their future. But, from the perspective of climate change, it doesn’t look too promising, except in the great promise of what might arise in them as resistance.

I think, for me, particularly working with first-generation young Latinx students that they have really been taught the survival notion of the American Dream. Their parents are saying, “Mijo, mija, get an education and make yourself the money.” They are being asked to see the world as a progressive plotline from ‘not having’ to ‘having’. But beneath it all, they are also receiving a deeper message, which is to be “responsible” to something greater than a career: to their family, their community and ultimately to their planet. If they can draw that connection from home values to world values, they could become especially emboldened warriors in the world that's in front of them. But to counter those narratives of the American Dream is really, really hard.

COLÓN: You mentioned earlier the concept of cultural amnesia and this obliviousness that we live in and how you are mirroring your mother's experience of memory loss with what we are witnessing today. Is the main contribution of your work to make us more aware of our identity and our origins? How does consciousness fit into this?

MORAGA: Well, yes, I just feel like, I’ve been writing about cultural loss since my collection of writings, The Last Generation; that is, at least since 1992. It was the Quincentenary, 500 years since Columbus. It was a really key moment for me where, the idea of decolonial thinking was leaving academia and just beginning to hit a broader base as a public conversation. But for me I couldn't think about decolonization without deindianization. How do you break something down (deconstruct it), without seeing what was there before its construction? If we look at América, what came before was indígena.

When I look at all the centroamericanos en los caravanas, coming in, arriving at la frontera, they are mostly Indigenous people, but everybody is being told to identify with their nation state. I’m supposed to just say, “I'm an American,” and they're supposed to say they're Guatemalan or Honduran or Salvadoran. But the fact of the matter is that one of the most progressive ways to counter the terror and displacement caused by the greed and corruption of our respective nation-states, is to recognize and affirm that we are also part of a pueblo, that we have an origin story, and that that origin story for us as people, as mestizos in the United States, and as indigenous people, helps us understand that we were de-indianized strategically. I think that it reflects a critical moment of consciencia when you, as a teacher, tell someone this and they can recognize that historical moment in their own story. This is so evident in many of my students where some of them are just one generation away from speaking Zapotec. In their bodies and through their presence in this country, the U.S. is being re-Indianized. I see in their faces how the world as they thought they knew it just took a giant flip and the mirror is pointed in their direction. They tell me with their eyes — “Are you crazy? Look at you, you're a professor, you've got all this good going for you. You are the living breathing American Dream. And you're asking me to go back to my origins?” And I answer, “Absolutely.” They do not have to choose spiritual poverty to no longer be poor. And they do not have to be alone in this. There's a movimiento de consciencia that's developing. “Consciencia” is not about “I” but “we.” There's power in that moment of discovery. Ironically, it was what they learned at home in the first place.

COLÓN: What is the worldview that the Chicano Movement upholds and do you think that Brazil can learn anything from this movement?

MORAGA: Well, I mean, that's huge, I'm not so sure. I think we have a lot to learn from Brazil’s own histories of resistance. We learn from one another. But, do I feel that the phenomenon of the Chicano movement, including all those people of color and anti-establishment movements that happened in the U.S. in the sixties and onward, offer enormous lessons regarding the power of grass root organizing, especially in exposing the internal colonization in so-called Western democracies? Yes. Those movements, from the Civil Rights campaigns more than fifty years ago and onward, have taught us a great deal about the limitations of capitalist patriarchy to free us as people of color, as women and as queer folk.

In the United States, if you have access to opportunity, you're just supposed to take the goods and run and never look back. What the United States teaches us every single day is assimilation and commodification. Every single day it teaches us amnesia, every single day our education tells us we don’t really exist. You learn so much about the Greeks and the Romans and European cultures and WASP American history, that by the time you get through high school, and choose a University major (if you get there!) you're totally scripted to look exclusively through a Western lens. This really is ‘the belly of the beast,’ swallowing you up into cultural oblivion.

The American Dream is a myth and yet, we cling to it in a way that has us waiting for a Messiah to lead us there. So many thought that having a Black president was going to change the world. It gave people hope, but politically in those eight years, blood spilled from Obama’s hand, through his drone strikes and immigration policies alone. Yes, the man's hands were tied, you know, by a Republican congress, but a black face wasn't going to make it different, although his eloquence continued to inspire. But, even a Black man becoming president didn’t fundamentally change society. It only exposed the racism woven into the very fabric of American society that reconstituted itself in the election of Donald Trump. So, that within less than three years, “I” and “me, first” and competition and “make it or break it” has been reinstituted as “Make America White Again.” This is our “Fordlândia [1]” of the 21st century, where a single individual believes he has the right to independently determine the future of a foreign country and its peoples. What’s been going on in Brazil right now — the conflation of politics with utter corruption, the lies, the cover-ups — is comparable. There's corruption in México, corruption in Honduras, corruption in the United States. What do you think, there's no corruption in the United States? The United States is completely run by lobbying, completely run by corporate interests, so I could say, “What do we have to learn from Brazil?” We're all suffering the same monster!” Some more than others. The way you approach any radical activism must be very specific to one’s land base — from our neighborhood barrios to the Amazon forest. White Capitalist Patriarchy steals and hordes. In response, we ask one another, who are your people? To see ourselves as a sovereign pueblos in the ‘belly of the beast’ can be very powerful political strategy; it's not separatist. It makes us the Brazilian peoples’ allies. It is a worldview that allows for cultural specificity, our sites of knowledge, our visions of the future, our stories, and our strategies for survival and coexistence in cooperation with other pueblos globally.

MORAGA: Well, I mean, that's huge, I'm not so sure. I think we have a lot to learn from Brazil’s own histories of resistance. We learn from one another. But, do I feel that the phenomenon of the Chicano movement, including all those people of color and anti-establishment movements that happened in the U.S. in the sixties and onward, offer enormous lessons regarding the power of grass root organizing, especially in exposing the internal colonization in so-called Western democracies? Yes. Those movements, from the Civil Rights campaigns more than fifty years ago and onward, have taught us a great deal about the limitations of capitalist patriarchy to free us as people of color, as women and as queer folk.

In the United States, if you have access to opportunity, you're just supposed to take the goods and run and never look back. What the United States teaches us every single day is assimilation and commodification. Every single day it teaches us amnesia, every single day our education tells us we don’t really exist. You learn so much about the Greeks and the Romans and European cultures and WASP American history, that by the time you get through high school, and choose a University major (if you get there!) you're totally scripted to look exclusively through a Western lens. This really is ‘the belly of the beast,’ swallowing you up into cultural oblivion.

The American Dream is a myth and yet, we cling to it in a way that has us waiting for a Messiah to lead us there. So many thought that having a Black president was going to change the world. It gave people hope, but politically in those eight years, blood spilled from Obama’s hand, through his drone strikes and immigration policies alone. Yes, the man's hands were tied, you know, by a Republican congress, but a black face wasn't going to make it different, although his eloquence continued to inspire. But, even a Black man becoming president didn’t fundamentally change society. It only exposed the racism woven into the very fabric of American society that reconstituted itself in the election of Donald Trump. So, that within less than three years, “I” and “me, first” and competition and “make it or break it” has been reinstituted as “Make America White Again.” This is our “Fordlândia [1]” of the 21st century, where a single individual believes he has the right to independently determine the future of a foreign country and its peoples. What’s been going on in Brazil right now — the conflation of politics with utter corruption, the lies, the cover-ups — is comparable. There's corruption in México, corruption in Honduras, corruption in the United States. What do you think, there's no corruption in the United States? The United States is completely run by lobbying, completely run by corporate interests, so I could say, “What do we have to learn from Brazil?” We're all suffering the same monster!” Some more than others. The way you approach any radical activism must be very specific to one’s land base — from our neighborhood barrios to the Amazon forest. White Capitalist Patriarchy steals and hordes. In response, we ask one another, who are your people? To see ourselves as a sovereign pueblos in the ‘belly of the beast’ can be very powerful political strategy; it's not separatist. It makes us the Brazilian peoples’ allies. It is a worldview that allows for cultural specificity, our sites of knowledge, our visions of the future, our stories, and our strategies for survival and coexistence in cooperation with other pueblos globally.

Photo by Marcos Colón

COLÓN: Your major contributions since the 1980s have been so powerful and have started changing the way we talk about identity in the United States. What do you think is left to do and what is your vision of the future?

MORAGA: Well, I mean, the only word that ever comes to me is consciencia. We can all thank Paulo Freire[2] for that. As an educator, what I just work at every single time in every class I teach is to help students uncover in themselves sites of agitation or discomfort as the basis for deeper self-reflection toward political engagement. What I believe in is that when we feel that sense of agitation, it proffers the possibility for the birth of consciousness, because something collides perhaps with how we've been raised, or what we've been told. I'm talking very particularly, because that's what I believe makes for a revolution: perhaps one specific moment. It's not the rhetoric coming from outside, it’s something within you that says, “This picture is not correct.” To make the connection that your condition, whether it is one of silence or servitude or both, is not your private individual problem; that it is systemic, and when you begin to understand there's a ‘we’ in that and not just ‘I,’’ that is the aperture for personal change, social consciousness and ultimately action. You begin to make connections with others that think that way from actual reflection and experience; and not from mere rhetorical jargon. Remember, it is the poets that have always changed the world, right? It is that crazy person who sees these contradictions and speaks to the sites of contradiction, right? So what my hope is, and maybe it’s naïve, is that I want people to get free! I just want them to get free. That freedom then is worth a lot. I’ve seen some of the most privileged people that ironically are enslaved by their money. Yes, you want an equitable world, I want an equitable world, but I don't want a monocultural world. That’s not free, that’s repression. The same way we’re talking about losing species, we’re losing not just languages but we're losing cultural values by the day and the dollar. My hope is to see the regeneration happen, the same way I’m talking about re-indianization. I want to see regeneration happen. To regenerate this planet is also cultural. Some days I wake up in the morning mourning the loss of stories, stories that could heal us, stories that change us for the better.

COLÓN: There is a very famous phrase from Percy Shelley[2] in the nineteenth century. He mentioned that “the poets are the legislators of the world.” Do you believe this phrase is valid today? Why does your work as a poet matter?

MORAGA: I wish so! When I was young, I could talk pretty well so everyone would say, “You should be a lawyer! You should be a lawyer!” I’m so glad I decided not to be a lawyer. Of course, we need lawyers and legislators on our side, but we also need poets. It's the true poet who addresses the contradictions, who understands paradoxes, who is never dogmatic because dogma does not reflect the human condition. It's the poets who can live in that place generated from both sides of the brain. I wish the poets were legislators because in that way then too the world becomes broader, and not in a liberal sense in any way.

For my part, I am a living contradiction. I’m a light-skinned woman, una mestiza, I got all kinds of DNA running through me. But I do know that the practice of poetry took me home. It required me to remember and to recognize in my family, whether they see it or not, that we have indigenous origins in this land, and that the nation state is not the full arbitrator of our identity. The poet figured that out.

We need laws that actually have the permeability to move and meet how the planet’s changing, how the world’s changing, how consciencia changes, how languages change, and evolve. My vision of the world is a cultural evolution that grows through critique, that evolves in accordance with an evolving planet in organic responsible ways. The sites in which our culture limits us, for example, as mujeres or as queer people need to be challenged. Culture is not a static entity, it is not romantic, it is always en lucha. I feel grateful that in my life there’s been honest struggle most of the time, but also times of great joy. Not just good times because everybody likes to party, that’s cool. But real joy occurs when something got freed, and you can look around you and you see people and you think, “Oh wow man, they're in their bodies, you know, they’re in their bodies. They’re owning their brown selves, their queer selves, their female selves,” whatever it is, and that’s joy. It usually happens with other people (in the deepest sense of “solidaridad”) or in profound reunion spiritually with the natural world.

COLÓN: Your work really paints a portrait that brings a sense of freedom and hope for humankind. How do you use viscerality in your poetry and how does this all connect to the notion of "home"?

MORAGA: I write with my body. I stand up, walk around. I’m first generation college-educated, so my original sense about literature is oral. Growing up, we didn't have books in our home. Instead, I listened to the stories of my familia — my tías, my tíos and my abuelita. For me, the writing process is very visceral because stories first emerge from the spoken word. It becomes a liberatory practice. Embodied expression allows you greater freedom to move in the world, because we move in the world as embodied people.

COLÓN: Carrying on with this idea of embodied people, how does going home embody change and how do you propose people go home and find their identity?

MORAGA: Again, this is not about nostalgia, but about a rigorous practice of return. In order to walk free in this world, every person has to reconcile with their past — the good and bad; the passively indifferent and the ruthlessly violent. From the most privileged to the most impoverished backgrounds, our ‘homes’ have shaped us. In the best of practices, out of that reckoning, emerges a renewed consciousness regarding the next steps in one’s life. Whether our return requires us to take up residence in our original homeland or to take to the road, our consciousness has changed through return and we can walk much more grounded on this planet, a planet that so desperately needs our sound wisdom.

I think of my son, who is now twenty-six years old. He often reminds me, “My politics and my vision of the world are not going to be your vision.”

Oh, how we would argue sometimes! I mean, he’s a very challenging person and I have to respect him, you know? He’s one living example of someone who has really taught me over the years about the requirement of living an authentic life. He’s not all there yet, but he is on his road and his road is different from mine, as he often reminds me. When I say I grew up with no books in my house, he grew up with hundreds of books in our home. So how he understands his class background is different from mine. His journey home requires a different set of strategies, a different set of questions. The ways in which he understands himself as an Indigenous person, as man of color, is very distinct from me as a light-skinned woman. He was raised with Indigenous spiritual practices growing up in our home. Growing up I had to leave home to shed a repressive Catholicism. Still, I also know things culturally as the daughter of a Mexican woman born in 1914 that he may never know.

I see all that same promise in my students. I tell them to go home. I see the courage it takes especially for the Latinx students. But, it's not to get stuck there; it’s to look at home, to feel home, to listen deeply to the unspoken messages of home; and to consider the ways in which, in the next generation, those hard-won home lessons might be of use (in rejection and or in embrace) in plotting out a roadmap toward a restored future.

COLÓN: Thank you so much.

MORAGA: Well, I mean, the only word that ever comes to me is consciencia. We can all thank Paulo Freire[2] for that. As an educator, what I just work at every single time in every class I teach is to help students uncover in themselves sites of agitation or discomfort as the basis for deeper self-reflection toward political engagement. What I believe in is that when we feel that sense of agitation, it proffers the possibility for the birth of consciousness, because something collides perhaps with how we've been raised, or what we've been told. I'm talking very particularly, because that's what I believe makes for a revolution: perhaps one specific moment. It's not the rhetoric coming from outside, it’s something within you that says, “This picture is not correct.” To make the connection that your condition, whether it is one of silence or servitude or both, is not your private individual problem; that it is systemic, and when you begin to understand there's a ‘we’ in that and not just ‘I,’’ that is the aperture for personal change, social consciousness and ultimately action. You begin to make connections with others that think that way from actual reflection and experience; and not from mere rhetorical jargon. Remember, it is the poets that have always changed the world, right? It is that crazy person who sees these contradictions and speaks to the sites of contradiction, right? So what my hope is, and maybe it’s naïve, is that I want people to get free! I just want them to get free. That freedom then is worth a lot. I’ve seen some of the most privileged people that ironically are enslaved by their money. Yes, you want an equitable world, I want an equitable world, but I don't want a monocultural world. That’s not free, that’s repression. The same way we’re talking about losing species, we’re losing not just languages but we're losing cultural values by the day and the dollar. My hope is to see the regeneration happen, the same way I’m talking about re-indianization. I want to see regeneration happen. To regenerate this planet is also cultural. Some days I wake up in the morning mourning the loss of stories, stories that could heal us, stories that change us for the better.

COLÓN: There is a very famous phrase from Percy Shelley[2] in the nineteenth century. He mentioned that “the poets are the legislators of the world.” Do you believe this phrase is valid today? Why does your work as a poet matter?

MORAGA: I wish so! When I was young, I could talk pretty well so everyone would say, “You should be a lawyer! You should be a lawyer!” I’m so glad I decided not to be a lawyer. Of course, we need lawyers and legislators on our side, but we also need poets. It's the true poet who addresses the contradictions, who understands paradoxes, who is never dogmatic because dogma does not reflect the human condition. It's the poets who can live in that place generated from both sides of the brain. I wish the poets were legislators because in that way then too the world becomes broader, and not in a liberal sense in any way.

For my part, I am a living contradiction. I’m a light-skinned woman, una mestiza, I got all kinds of DNA running through me. But I do know that the practice of poetry took me home. It required me to remember and to recognize in my family, whether they see it or not, that we have indigenous origins in this land, and that the nation state is not the full arbitrator of our identity. The poet figured that out.

We need laws that actually have the permeability to move and meet how the planet’s changing, how the world’s changing, how consciencia changes, how languages change, and evolve. My vision of the world is a cultural evolution that grows through critique, that evolves in accordance with an evolving planet in organic responsible ways. The sites in which our culture limits us, for example, as mujeres or as queer people need to be challenged. Culture is not a static entity, it is not romantic, it is always en lucha. I feel grateful that in my life there’s been honest struggle most of the time, but also times of great joy. Not just good times because everybody likes to party, that’s cool. But real joy occurs when something got freed, and you can look around you and you see people and you think, “Oh wow man, they're in their bodies, you know, they’re in their bodies. They’re owning their brown selves, their queer selves, their female selves,” whatever it is, and that’s joy. It usually happens with other people (in the deepest sense of “solidaridad”) or in profound reunion spiritually with the natural world.

COLÓN: Your work really paints a portrait that brings a sense of freedom and hope for humankind. How do you use viscerality in your poetry and how does this all connect to the notion of "home"?

MORAGA: I write with my body. I stand up, walk around. I’m first generation college-educated, so my original sense about literature is oral. Growing up, we didn't have books in our home. Instead, I listened to the stories of my familia — my tías, my tíos and my abuelita. For me, the writing process is very visceral because stories first emerge from the spoken word. It becomes a liberatory practice. Embodied expression allows you greater freedom to move in the world, because we move in the world as embodied people.

COLÓN: Carrying on with this idea of embodied people, how does going home embody change and how do you propose people go home and find their identity?

MORAGA: Again, this is not about nostalgia, but about a rigorous practice of return. In order to walk free in this world, every person has to reconcile with their past — the good and bad; the passively indifferent and the ruthlessly violent. From the most privileged to the most impoverished backgrounds, our ‘homes’ have shaped us. In the best of practices, out of that reckoning, emerges a renewed consciousness regarding the next steps in one’s life. Whether our return requires us to take up residence in our original homeland or to take to the road, our consciousness has changed through return and we can walk much more grounded on this planet, a planet that so desperately needs our sound wisdom.

I think of my son, who is now twenty-six years old. He often reminds me, “My politics and my vision of the world are not going to be your vision.”

Oh, how we would argue sometimes! I mean, he’s a very challenging person and I have to respect him, you know? He’s one living example of someone who has really taught me over the years about the requirement of living an authentic life. He’s not all there yet, but he is on his road and his road is different from mine, as he often reminds me. When I say I grew up with no books in my house, he grew up with hundreds of books in our home. So how he understands his class background is different from mine. His journey home requires a different set of strategies, a different set of questions. The ways in which he understands himself as an Indigenous person, as man of color, is very distinct from me as a light-skinned woman. He was raised with Indigenous spiritual practices growing up in our home. Growing up I had to leave home to shed a repressive Catholicism. Still, I also know things culturally as the daughter of a Mexican woman born in 1914 that he may never know.

I see all that same promise in my students. I tell them to go home. I see the courage it takes especially for the Latinx students. But, it's not to get stuck there; it’s to look at home, to feel home, to listen deeply to the unspoken messages of home; and to consider the ways in which, in the next generation, those hard-won home lessons might be of use (in rejection and or in embrace) in plotting out a roadmap toward a restored future.

COLÓN: Thank you so much.

|

Interview by

Marcos Colón 3/11/2020 |

Marcos Colón is the Dean’s postdoctoral and Gannon fellow post-doc in Portuguese at the Department of Modern Languages and Linguistics at Florida State University. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His area of specialization is Brazilian cultural and literary studies with a focus on representations of the Amazon in the twentieth- and twenty-first-century Brazilian literature and film from an environmental studies perspective. His previous works includes the production and direction of the documentary films: Beyond Fordlândia: An Environmental Account of Henry Ford’s Adventure in the Amazon and Zo’é based on his visit to the uncontacted Zo’é tribe (2018). He is interested in the post-rubber era and questions established representations of the tropics in literature and culture. He is the editor and creator of the Amazonia Latitude digital magazine.

|

WORKS CITED

Moraga, Cherríe. The Native Country of a Heart: A Memoir. Farrar, Straust, and Giroux, 2019.

——. The Last Generation. South End Press, 1993.

——. A Xicana Codex of Changing Consciousness: Writing 2000-2010. Duke UP, 2001.

Moraga, Cherríe, and Gloria Anzaldúa, editors. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. 1981. 4th ed., SUNY Press, 2015.

Moraga, Cherríe, Alma Gómez, and Mariana Romo-Carmona, editors. Cuentos: Stories by Latinas. Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, 1983.

[1] Cherríe Moraga is alluding to the documentary Beyond Fordlândia (2017, 75min), which narrates ninety years on from Ford’s Amazonian failure that left ravaged lands and a ghost town of shattered dreams. In 1927 the Ford Motor Company attempted to establish rubber plantations on the Tapajós River, a primary tributary of the Amazon, yet Ford's pioneering project was doomed to failure and provides a cautionary tale of senseless exploitation. The film draws parallels with the Ford era in addressing the recent transition from failed rubber to successful soybean cultivation, highlighting the heartbreaking implications for Amazonia and its people.

[2] Paulo Reglus Neves Freire was a Brazilian educator and philosopher, and a leading advocate of critical pedagogy. He is best known for his influential work, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 1970, generally considered a foundation for the critical pedagogy movement.

[3] Percy Bysshe Shelley was an English Romantic poet of the 19th century, often regarded as among the finest lyric and philosophical poets in the English language. As radical in his poetry as in his political and social views, Shelley was a key member of a close circle of visionary poets and writers that included Lord Byron, John Keats, Thomas Love Peacock and his own second wife, Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein.

[2] Paulo Reglus Neves Freire was a Brazilian educator and philosopher, and a leading advocate of critical pedagogy. He is best known for his influential work, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 1970, generally considered a foundation for the critical pedagogy movement.

[3] Percy Bysshe Shelley was an English Romantic poet of the 19th century, often regarded as among the finest lyric and philosophical poets in the English language. As radical in his poetry as in his political and social views, Shelley was a key member of a close circle of visionary poets and writers that included Lord Byron, John Keats, Thomas Love Peacock and his own second wife, Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein.

|

Comment Box is loading comments...

|

|