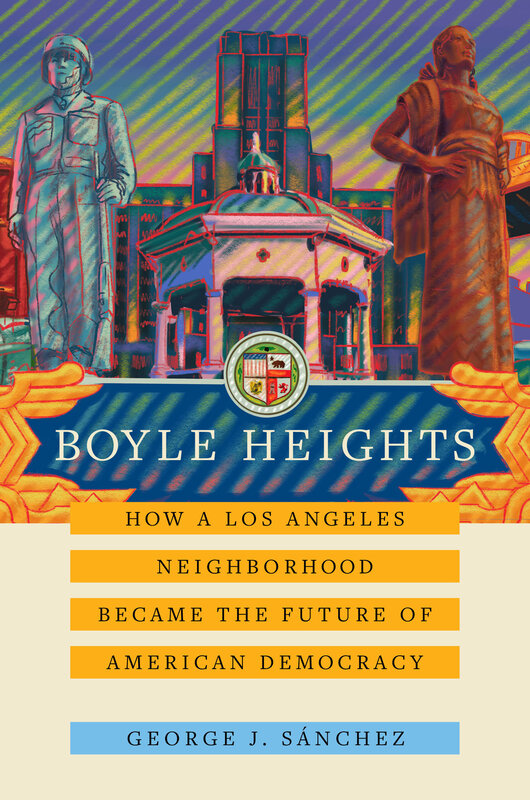

Boyle Heights

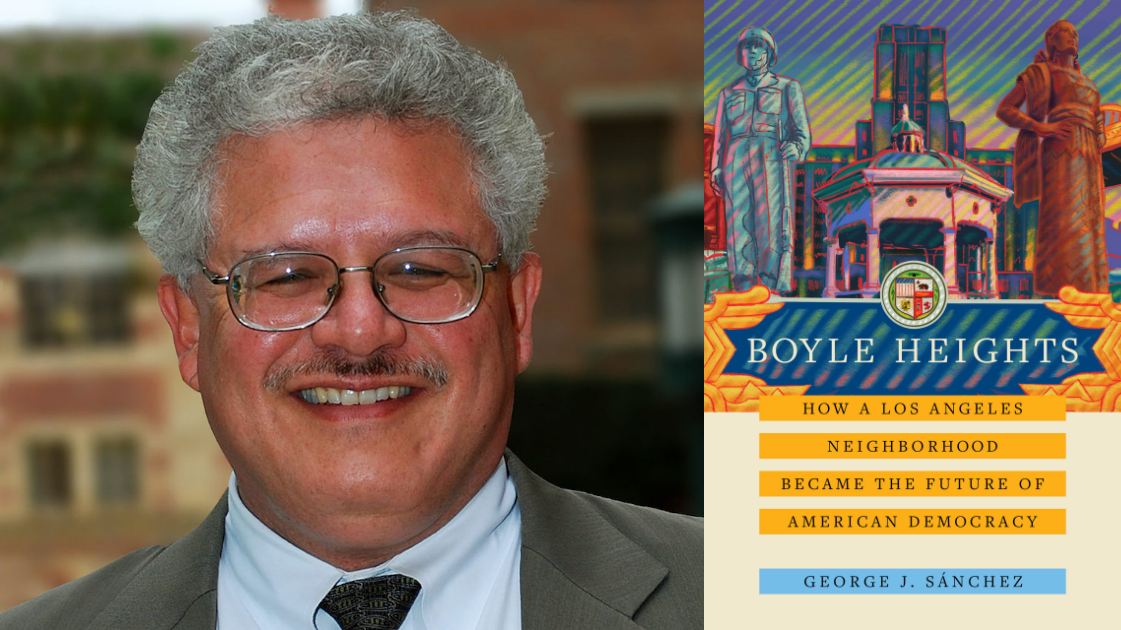

George J. Sánchez

|

When you purchase a book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission and so do independent book stores.

|

In the annals of Chicanx history, only a few historians stand heads and shoulders above the rest. One of those is George J. Sánchez whose recent publication, Boyle Heights: How a Los Angeles Neighborhood Became the Future of Democracy, leaves off where his award-winning Becoming Mexican American made its mark roughly three decades ago. That book illuminated a distinctive history of Mexicans/Mexican Americans in Eastside Los Angeles with vibrant chapters on repatriation, family life, music, and the rise of the second generation. But, in his recent book, Sanchez is quick to point out that Becoming Mexican American represented only one tile in the dazzling mosaic of 20th century Boyle Heights, a community that has been comprised of myriad ethnic and racial groups, including Mexican/Mexican Americans, African Americans, Japanese Americans and Jewish Americans. The author masterfully unravels a paramount historical question examining "how this community came to be a thriving community over time and how the legacy of this progressive multiracialism continues to be a powerful influence over residents when the neighborhood became overwhelmingly Latino in the last third of the 20th century."(4) Curiously, Boyle Heights was to be designated as a white-only enclave. City leaders hoped it would help attract white boosters from the East coast as "the first suburb of refined whiteness." (29) Of course, the community evolved much differently stemming from its geographic location and municipal ordinances: Boyle Heights was remote-- located east of the Los Angeles River. It would be several decades before transportation arteries and famously the Sixth Street Bridge (and other bridges) connected the community to downtown. Racial covenants--city ordinances preventing BIPOC from settling in a neighborhood--shaped most Los Angeles throughout the first half of the 20th century. But, Boyle Heights lacked such ordinances, leading it to become a veritable multiethnic neighborhood. |

Most of the residents of Boyle Heights, including Jewish, Mexicans, and Molokans, had been steeped in radical politics—Mexicans influenced by the anti-Diaz Partido Liberal Mexicano and the activism of the Flores Magon brothers and Jewish immigrants influenced by radical Zionism and the Russian Revolution. Later, these groups were joined by Japanese Americans and African Americans, both groups blocked from settling in other racially segregated Los Angeles neighborhoods. And, this is just the point: the history of Boyle Heights shows us migrants who "share radical traditions from their homelands, even while the rise of nationalist sentiments and segregated enclaves in the period led them to strengthen their own ethnic sense of self." (66)

With the advent of the Great Depression--and a decade later, World War II-- residents of Boyle Heights endured acute racism. Under strapped financial circumstances, many Mexican laborers lost their jobs, requiring public assistance. Repatriation, a plan jointly sponsored by the U.S. and Mexican governments, became a convenient way to expunge unwanted racial-ethnic groups from Los Angeles. Massive deportations occurred, resulting in more than 13,000 L.A. Mexicans (and many Mexican-Americans) being sent back to Mexico by 1934. Plans for a second Repatriation Program were well afoot by 1941; however, with the bombing of Pearl Harbor, a new racial scapegoat emerged in Japanese Americans. Those histories of exploitation were not mutually exclusive as Sanchez cogently argues, racialized narratives can be interlocking as "patterns of dehumanization against one racialized group can be transferred into policy against another. . . "(68) Thus, by February 1942, Executive Order 9066 formalized the evacuation of Japanese/Japanese Americans as "enemy aliens." Summoned by evacuation orders, Japanese Americans quickly packed up and were sent to Santa Anita Racetrack before being sent to such internment camps as Manzanar. But, neighborhood residents rallied together to support internees, protecting their residential properties and personal belongings until they returned.

Another problem that emerged was the attempt to dislocate Mexicans from Boyle Heights to make way for freeways and public housing. L.A. stakeholders reasoned that to improve the neighborhood, poor people needed to be expelled. Public housing projects emerged in the 1940s purportedly epitomizing "New Deal reform" politics. In reality, these same programs were restricted to "American born" and/or military families, denying Mexicans and others from the benefits of the programs. Dislocation would be a common theme for populations like Mexican immigrants and others deemed "disposable people."

Following World War II, the exodus of Jewish Americans began in earnest. They established communities in Westside L.A. and the San Fernando Valley for the first time. Factors such as federal entitlement programs like the G.I. Bill and F.H.A. loans favored Jewish residents of Boyle Heights. For example, G.I. Bill alone created higher educational opportunities previously unrecognized. Two decades later, deindustrialization changed the composition of Boyle Heights. Small-scale sweatshops and nonunionized manufacturing drew a new group of workers: low-wage, often undocumented workers skeptical of unionized labor. It was a sweatshop owner's dream. Meanwhile, Mexican Americans moved out of Boyle Heights into eastern Los Angeles suburbs, while the availability of public housing for undocumented newcomers and the transformation of multilingual Boyle Heights into a Spanish-speaking enclave welcomed the new Latinx immigrants.

In the 21st century, Boyle Heights remains a vibrant, Spanish-speaking community, but one that faces problems characteristic of many L.A. neighborhoods. Will gentrification translate into the trendy millennial havens such as that of Echo Park? Or will Boyle Heights remain a welcoming home to its undocumented Latinx residents? Sanchez does not attempt to foretell the future of Boyle Heights but rather to set the record straight about the past: "only by confronting multiple histories and contemporary conditions . . . may the true power of the multiracial past of Los Angeles be recognized for its importance and its continued impact on the lives of us all." (264)

Historian George J. Sanchez is a professor of American Studies & Ethnicity and History and the University of Southern California and the author of the award-winning book Becoming Mexican-American: Ethnicity, Culture and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900-1945.

Boyle Heights: How a Los Angeles Neighborhood Became the Future of Democracy is a publication by University of California Press. Click here to purchase.

With the advent of the Great Depression--and a decade later, World War II-- residents of Boyle Heights endured acute racism. Under strapped financial circumstances, many Mexican laborers lost their jobs, requiring public assistance. Repatriation, a plan jointly sponsored by the U.S. and Mexican governments, became a convenient way to expunge unwanted racial-ethnic groups from Los Angeles. Massive deportations occurred, resulting in more than 13,000 L.A. Mexicans (and many Mexican-Americans) being sent back to Mexico by 1934. Plans for a second Repatriation Program were well afoot by 1941; however, with the bombing of Pearl Harbor, a new racial scapegoat emerged in Japanese Americans. Those histories of exploitation were not mutually exclusive as Sanchez cogently argues, racialized narratives can be interlocking as "patterns of dehumanization against one racialized group can be transferred into policy against another. . . "(68) Thus, by February 1942, Executive Order 9066 formalized the evacuation of Japanese/Japanese Americans as "enemy aliens." Summoned by evacuation orders, Japanese Americans quickly packed up and were sent to Santa Anita Racetrack before being sent to such internment camps as Manzanar. But, neighborhood residents rallied together to support internees, protecting their residential properties and personal belongings until they returned.

Another problem that emerged was the attempt to dislocate Mexicans from Boyle Heights to make way for freeways and public housing. L.A. stakeholders reasoned that to improve the neighborhood, poor people needed to be expelled. Public housing projects emerged in the 1940s purportedly epitomizing "New Deal reform" politics. In reality, these same programs were restricted to "American born" and/or military families, denying Mexicans and others from the benefits of the programs. Dislocation would be a common theme for populations like Mexican immigrants and others deemed "disposable people."

Following World War II, the exodus of Jewish Americans began in earnest. They established communities in Westside L.A. and the San Fernando Valley for the first time. Factors such as federal entitlement programs like the G.I. Bill and F.H.A. loans favored Jewish residents of Boyle Heights. For example, G.I. Bill alone created higher educational opportunities previously unrecognized. Two decades later, deindustrialization changed the composition of Boyle Heights. Small-scale sweatshops and nonunionized manufacturing drew a new group of workers: low-wage, often undocumented workers skeptical of unionized labor. It was a sweatshop owner's dream. Meanwhile, Mexican Americans moved out of Boyle Heights into eastern Los Angeles suburbs, while the availability of public housing for undocumented newcomers and the transformation of multilingual Boyle Heights into a Spanish-speaking enclave welcomed the new Latinx immigrants.

In the 21st century, Boyle Heights remains a vibrant, Spanish-speaking community, but one that faces problems characteristic of many L.A. neighborhoods. Will gentrification translate into the trendy millennial havens such as that of Echo Park? Or will Boyle Heights remain a welcoming home to its undocumented Latinx residents? Sanchez does not attempt to foretell the future of Boyle Heights but rather to set the record straight about the past: "only by confronting multiple histories and contemporary conditions . . . may the true power of the multiracial past of Los Angeles be recognized for its importance and its continued impact on the lives of us all." (264)

Historian George J. Sanchez is a professor of American Studies & Ethnicity and History and the University of Southern California and the author of the award-winning book Becoming Mexican-American: Ethnicity, Culture and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900-1945.

Boyle Heights: How a Los Angeles Neighborhood Became the Future of Democracy is a publication by University of California Press. Click here to purchase.

|

Comment Box is loading comments...

|

|