Land Grab: The Untold Story of Fort Brown

by Sara C. Bronin

I. “I Believe in Miracles”

“I believe in miracles, and just maybe you are the one to do something about this,” said the cover note accompanying a thick package of historical documents, clippings from the Brownsville Herald, and various family trees. It’d been sent to me two years ago from my mom’s cousin, Bertie Lucio Caballero, the genealogist of our family. A retired schoolteacher, she has spent nearly four decades piecing together public and private records.[1] With her package, she was appointing me to the task of making sense of a property transfer one hundred and seventy-five years old—one that has haunted our family for eight generations.

Family lore holds that the United States government robbed us of a huge tract of prime land on the Rio Grande River. The purportedly stolen land encompassed the southernmost part of the southernmost city in Texas—Brownsville—and became the site for Fort Brown, the military stronghold from which the United States successfully won the Mexican-American War in 1848. Bertie told me she believed that as a property law professor, I could help right this wrong. She ended her cover letter with a hope for compensation: “Maybe, [our ancestor] will rest in peace, when we, his descendants, receive the monies we rightfully deserve.”

When I got her request, I felt conflicted. From a practical perspective, I might have seemed like a good fit for the task. My legal expertise includes land titling, and my longtime passion has been the historic preservation of buildings and sites. I’ve publicly spoken and written about the importance of what preservationists call “telling the full story” about the past, in all of its messiness and contradictions.

But the truth was, I did not give much credence to my family’s tales. They seemed entirely implausible. One of the very first things you learn in law school is that the United States Constitution requires that governments exercising eminent domain—seizing private land for public use—compensate the owners for the land’s fair market value. There are many legal cases where property owners claim that they are not paid enough. But not paid at all? I had never read a case like that.

Nonetheless, I promised Bertie that I would look into it. My research would involve reviewing the family tree, deciphering court cases well over a century old, interviewing family members, and reading historical analyses. It would reveal the unexpected, confirming that our ancestor, Miguel Salinas, was indeed wronged. It would also reveal that Bertie’s and my branch of the family had no claim, because Salinas passed his interest in the property to another branch. It would reinforce a heavy truth: that property rights reward the most privileged, and that the way we award these rights can have profound ramifications on families for generations. And it would shift my own focus as a scholar, advocate, and professor—to color dry doctrine with the reality of the profound inequities embedded in our legal system.

|

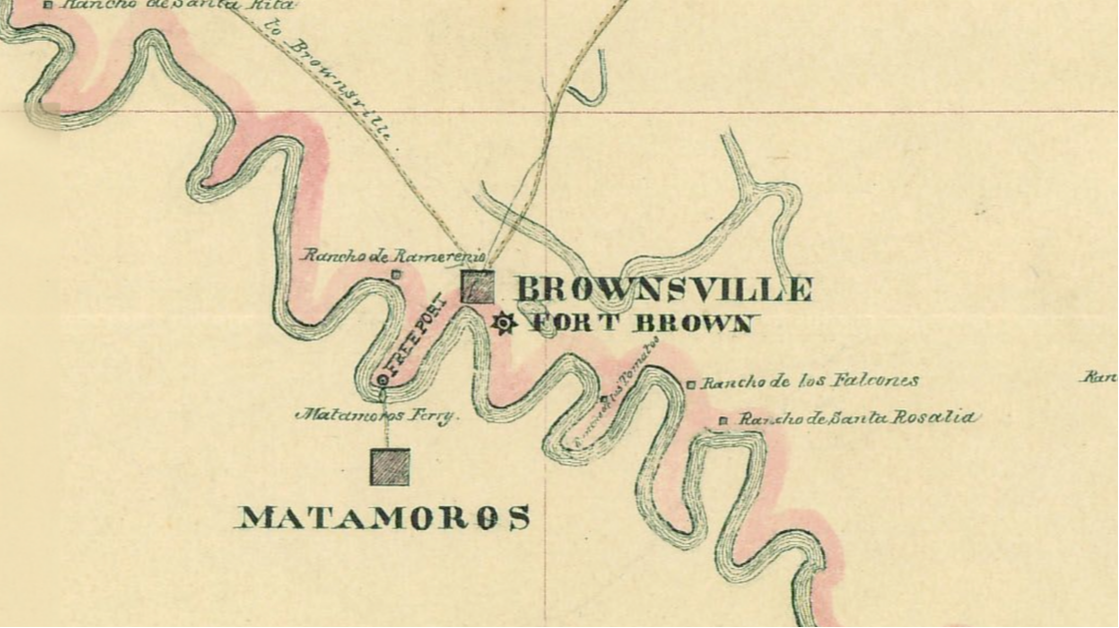

II. How The Land Was Passed

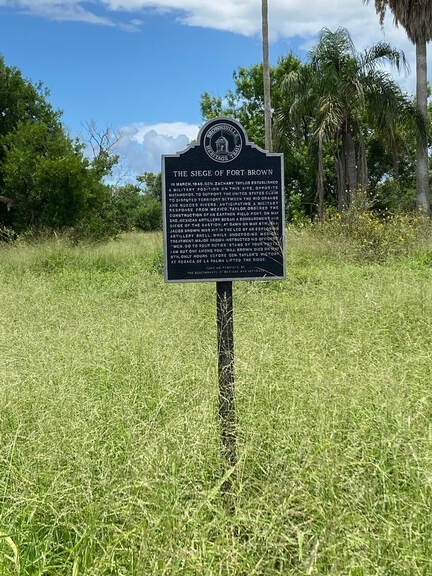

The site to which my family lays claim does not make its origins easy to trace. Last summer, when I made a pilgrimage there, I found a marker overgrown with vegetation. The marker announces the “Original Fort Brown Site” and mentions the “earthern fort… built by Gen. Zachary Taylor’s Troops,” describes the shape of the earthworks, and extols Jacob Brown as the “gallant commander who nobly fell in its defense.” History books expand upon these themes, making it seem as if Fort Brown simply materialized out of thin air, willed into being by a soon-to-be-victorious U.S. Army. Yet its story begins much earlier. In 1519, the Spanish “discovered” and started exploring the Rio Grande Valley, which had been occupied by nomadic Coahuiltecan tribes for thousands of years. The Spaniards did not begin to create settlements there in earnest until the mid-eighteenth century.[2] To ensure orderly colonization, the king offered grants of land to Spanish settlers.[3] In 1781, he bestowed the Portrero del Espíritu Santo (“pasture of the holy spirit”) Grant to a settler, José Salvador de la Garza.[4] It included more than four-hundred square miles of land—an area larger than all five boroughs of New York City—directly on the Rio Grande River.[5] |

After Salvador de la Garza died, his son inherited the property. By 1802, the Espíritu Santo Grant was held by the son’s widow, María Francesca Cavazos.[6] Unlike some countries, Spain allowed women in its colonies to own property, likely in recognition of the continuity that predictable land transfers brought to an unpredictable frontier.[7] After Mexico achieved independence from Spain in 1821, it honored Cavazos’s title, protecting her ownership despite the transfer of governments. She conveyed different parts of the land for different purposes. In 1826, she leased 23 acres to Miguel Salinas.[8] She sold those acres to a widow in 1833, who retained Salinas as a tenant and then sold the land to him two years later.[9]

According to Bertie’s files, Salinas was born in 1787 in Matamoros. He was married in 1808, when he was twenty-one. He had twelve children, at least seven of whom eventually got married and had children of their own. When he obtained ownership of the property, Salinas was forty-eight years old.

As a landowner, he was privileged, and he made the most of it. A good manager and rancher, he maintained a healthy herd of cattle and grew diverse and abundant crops of cotton, corn, sugar, cane, and beans. He built twelve brick buildings (some for his family, others for workers or storage), erected a windmill, and enclosed his land with a sturdy fence.[10] When Texas declared itself a Republic in 1836, the year after Salinas acquired his property, again all land titles were honored. His was secure, but other trouble loomed: Mexico and the United States looked headed for war over control of what we know now as Texas.

III. Wartime Dispossession

President James K. Polk believed in the country’s Manifest Destiny to expand westward to the Pacific Ocean. Though some of modern-day Texas had been peacefully annexed to the United States in 1845, a dispute over the location of the southern border lingered. Mexicans claimed it was the more-northern Nueces River, while the United States claimed it was the Rio Grande River.

In 1846, Polk sent General Zachary Taylor, who would soon succeed Polk as president, to the Rio Grande Valley. Taylor aimed to quickly establish a superior military position for the United States within the disputed territory. He did, changing the trajectory of both our country and my family. On April 14, 1846, Taylor claimed Salinas’ property in the name of the federal government.

No doubt Salinas was stunned and confused. Surrounded by a hostile occupying force of 4,000 troops, he had no choice but to “sign” a written lease with the quartermaster, G.H. Crossman. The lease was written in English, a language Salinas did not speak. When I next teach landlord-tenant law, I will distribute it as an example of an “unconscionable” lease: one so lopsided that it should not be enforced. Likely Salinas was also forced to sign under duress, by armed soldiers requesting his compliance. No one was there to explain his rights.

I wonder what went through his mind as he gathered his family and packed up his belongings to leave the life he had built and the land he had lived on for twenty years. I wonder how many hours Taylor’s troops gave him to vacate. I wonder what he left behind.

Situated on a bend in the Rio Grande, the Salinas property became a critical site for American troops before and during the Mexican-American War. Just three weeks after Taylor’s seizure, it saw its first battle. The Mexicans got the upper hand, killing two American soldiers, including Jacob Brown, for whom the fort was eventually named. Within the week, Taylor welcomed 2,400 fresh troops as reinforcements. A second battle, Resaca de la Palma, happened a day later—and this time the Mexicans were badly defeated. Shortly after Resaca de la Palma, Congress declared war.

The soldiers stationed at Fort Brown benefited not only from its perfect strategic location, but from the work Salinas had put into the land. The structures he had built became officers’ quarters, storage, and hospital facilities.[11] The Army used some of Salinas’s fencing to bomb-proof Fort Brown, and one of the cattle pens for horses.

Following the Salinas seizure, General Taylor went on to take a total of 360 acres of private property on the Rio Grande to secure the United States Army’s position and accommodate a growing number of troops.[12] I did not trace the subsequent seizures, but it seems likely that other families’ wartime dispossession may be even more hidden than ours.

IV. After the War

One might say that all’s fair in love and war, and that land seized in conquest commonly changes hands. But it’s not so simple, in this case.

When the war ended in 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo established the Rio Grande as the riparian border between Mexico and the United States. It achieved Polk’s broader vision for American conquest in that Mexico ceded its entire interest in California and its interest all or part of eight other states between California and Texas. More relevant for our purposes, the Treaty recognized that all of the Spanish land grants were valid.[13]

In theory, this recognition provided Salinas with a clear chain of title, from the land grant to Salvador de la Garza through María Francesca Cavazos. His rights were further confirmed in the lease he had signed with quartermaster Crossman. In 1849, Crossman acknowledged that the military promised to pay $1.50 per day to Salinas as the owner.[14] (He also admitted that only $11.12 in partial rent was paid—in pork.) A lease of any kind implies what we call in property law a “future interest”: the landlord’s right to return to possession. But as the military continued to build out Fort Brown, Salinas must have come to understand that he would never again repossess that land. And there must have been some point when the military occupiers knew they would never give it back to him. At that point, the Army should have initiated an eminent domain proceeding, declaring in court that they were taking Salinas’s property and then working out compensation. But it didn’t happen.

Salinas asked for compensation anyway. As owner when Taylor seized the property, he was entitled to money for losing it completely. He failed to convince federal authorities of his entitlement. Here again, property law textbooks say that these facts present a classic case of a government taking, requiring that Salinas be paid for his loss. But again, the law as applied deviated from the law as written. Salinas, a borderland farmer who spoke no English, did not receive a protection enshrined among our most basic constitutional rights.

He hoped his son would fare better. In 1849, he transferred his entire interest in the property to his son José Antonio. That transfer severed my family’s interest, as we are descended of José Antonio’s brother, Juan Nepomuceno. As it turned out, José Antonio fared worse than his father, fighting not only the federal government for compensation, but others who began to make competing claims that they were the wronged owners. As my research shows, these people would use and abuse every property law tool available to undermine the Salinas claim, so that once compensation was finally offered, it never benefited Salinas’ descendants.

V. Not a Dime

The claims of those falsely asserting ownership of the Salinas property actually derived from the actions of María Francesca Cavazos herself. Simply put, she conveyed the same property twice, to different people. First, she sold it in 1833 to the widow who sold it to Miguel Salinas. Second, her will (administered after she died in 1835) purported to leave the Fort Brown property to her niece, María Josefa Cavazos.[15] Perhaps María Francesca simply forgot to revise her will.

Whatever the explanation, a double conveyance of the same property is not unheard of. Because it happens with some frequency, every state has laws identifying which of the competing claims will prevail. These “recording acts” are a key element in first-year property law courses and tested on the bar exam. Yet I was still surprised to unearth these facts, because the doctrine on the books, dating back to Roman times, would clearly render the Salinas heirs the victors. Nemo dat quod non habet: you cannot convey what you don’t own. Under this principle, recording acts would invalidate the second transfer, because the elder Cavazos no longer owned the property when she died. Moreover, her niece would not have been a “bona fide purchaser” as the acts typically require.

Yet that’s not how it worked out. Instead, the legal battles between successors to the Salinas chain and the María Josefa chain lasted for nearly sixty years. Public attention to these disputes reached a fever pitch in the decade after the war. In 1860, the Texas Supreme Court held that one lawsuit could not even be heard in Cameron County (where Brownsville holds the county seat) because of potential juror bias, reflected in “the formation of processions on both sides, the display of badges and banners, with inscriptions indicative of high feeling against each other… [such that] there is scarcely a citizen residing in the said counties who is not a partisan on one side or the other in this controversy.”[16]

The sordid details are laid out in dozens of judicial decisions, filings, Texas Attorney General opinions, and Congressional committee reports. The Salinas heirs kept filing lawsuits into the 1890s.[17] One name came up again and again: Stillman. Charles Stillman, a Connecticut-born entrepreneur, bought up land in the Rio Grande Valley (including other portions of the Portrero del Espíritu Santo grant). He became one of the richest men in America; his son James worked with him and inherited his various property interests.[18] As their last name suggests, they were White, not Mexican or Mexican-American. They had vast wealth and deep political connections that ultimately helped them acquire legal interests in both strands of the competing claims.

A few facts among many can illustrate how they did it. Stillman’s business partner, Major William Chapman, was quartermaster of Fort Brown when Miguel Salinas first claimed compensation.[19] In 1862, Stillman’s attorney, Stephen Powers, finagled a half-interest in any Salinas property from the son who did inherit it (José Antonio).[20] Then in 1875, Stillman negotiated a half-interest in the property from María Josefa Cavazos (the niece)—then got his associate appointed the administrator of the will to the party who held the other half.[21] Time and again, the historical documents show how Stillman outwitted Cavazos. Another egregious example involved a property near the Salinas tract, for which Stillman negotiated to pay just one-sixth of the value, though it is not clear he ever paid at all.[22]

The Stillmans’ connections likely were crucial in leading a Congressional committee in 1885 to appropriate $160,000 to compensate property owners for the Fort Brown taking.[23] The Secretary of War asked a critical question to the Attorney General of Texas: under state law, who gets the money? After review, the Attorney General suggested that the proceeds be split between Charles Stillman and another of Stillman’s associates. He acknowledged Salinas’s claim for unpaid rent but opined that the unpaid rent should not be compensated by the Congressional grant.[24] Despite trips to the Fifth Circuit[25] and even the Supreme Court of the United States,[26] the Salinas heirs ultimately received nothing. A 1905 visit to the U.S. Supreme Court seemed to end the mess of poorly-reasoned (or at least poorly-explained) decisions. The Court found that once compensation had been distributed to Stillman and his associates, the Court lacked jurisdiction to award a dime to the Salinas-descended claimants.

According to Bertie’s files, Salinas was born in 1787 in Matamoros. He was married in 1808, when he was twenty-one. He had twelve children, at least seven of whom eventually got married and had children of their own. When he obtained ownership of the property, Salinas was forty-eight years old.

As a landowner, he was privileged, and he made the most of it. A good manager and rancher, he maintained a healthy herd of cattle and grew diverse and abundant crops of cotton, corn, sugar, cane, and beans. He built twelve brick buildings (some for his family, others for workers or storage), erected a windmill, and enclosed his land with a sturdy fence.[10] When Texas declared itself a Republic in 1836, the year after Salinas acquired his property, again all land titles were honored. His was secure, but other trouble loomed: Mexico and the United States looked headed for war over control of what we know now as Texas.

III. Wartime Dispossession

President James K. Polk believed in the country’s Manifest Destiny to expand westward to the Pacific Ocean. Though some of modern-day Texas had been peacefully annexed to the United States in 1845, a dispute over the location of the southern border lingered. Mexicans claimed it was the more-northern Nueces River, while the United States claimed it was the Rio Grande River.

In 1846, Polk sent General Zachary Taylor, who would soon succeed Polk as president, to the Rio Grande Valley. Taylor aimed to quickly establish a superior military position for the United States within the disputed territory. He did, changing the trajectory of both our country and my family. On April 14, 1846, Taylor claimed Salinas’ property in the name of the federal government.

No doubt Salinas was stunned and confused. Surrounded by a hostile occupying force of 4,000 troops, he had no choice but to “sign” a written lease with the quartermaster, G.H. Crossman. The lease was written in English, a language Salinas did not speak. When I next teach landlord-tenant law, I will distribute it as an example of an “unconscionable” lease: one so lopsided that it should not be enforced. Likely Salinas was also forced to sign under duress, by armed soldiers requesting his compliance. No one was there to explain his rights.

I wonder what went through his mind as he gathered his family and packed up his belongings to leave the life he had built and the land he had lived on for twenty years. I wonder how many hours Taylor’s troops gave him to vacate. I wonder what he left behind.

Situated on a bend in the Rio Grande, the Salinas property became a critical site for American troops before and during the Mexican-American War. Just three weeks after Taylor’s seizure, it saw its first battle. The Mexicans got the upper hand, killing two American soldiers, including Jacob Brown, for whom the fort was eventually named. Within the week, Taylor welcomed 2,400 fresh troops as reinforcements. A second battle, Resaca de la Palma, happened a day later—and this time the Mexicans were badly defeated. Shortly after Resaca de la Palma, Congress declared war.

The soldiers stationed at Fort Brown benefited not only from its perfect strategic location, but from the work Salinas had put into the land. The structures he had built became officers’ quarters, storage, and hospital facilities.[11] The Army used some of Salinas’s fencing to bomb-proof Fort Brown, and one of the cattle pens for horses.

Following the Salinas seizure, General Taylor went on to take a total of 360 acres of private property on the Rio Grande to secure the United States Army’s position and accommodate a growing number of troops.[12] I did not trace the subsequent seizures, but it seems likely that other families’ wartime dispossession may be even more hidden than ours.

IV. After the War

One might say that all’s fair in love and war, and that land seized in conquest commonly changes hands. But it’s not so simple, in this case.

When the war ended in 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo established the Rio Grande as the riparian border between Mexico and the United States. It achieved Polk’s broader vision for American conquest in that Mexico ceded its entire interest in California and its interest all or part of eight other states between California and Texas. More relevant for our purposes, the Treaty recognized that all of the Spanish land grants were valid.[13]

In theory, this recognition provided Salinas with a clear chain of title, from the land grant to Salvador de la Garza through María Francesca Cavazos. His rights were further confirmed in the lease he had signed with quartermaster Crossman. In 1849, Crossman acknowledged that the military promised to pay $1.50 per day to Salinas as the owner.[14] (He also admitted that only $11.12 in partial rent was paid—in pork.) A lease of any kind implies what we call in property law a “future interest”: the landlord’s right to return to possession. But as the military continued to build out Fort Brown, Salinas must have come to understand that he would never again repossess that land. And there must have been some point when the military occupiers knew they would never give it back to him. At that point, the Army should have initiated an eminent domain proceeding, declaring in court that they were taking Salinas’s property and then working out compensation. But it didn’t happen.

Salinas asked for compensation anyway. As owner when Taylor seized the property, he was entitled to money for losing it completely. He failed to convince federal authorities of his entitlement. Here again, property law textbooks say that these facts present a classic case of a government taking, requiring that Salinas be paid for his loss. But again, the law as applied deviated from the law as written. Salinas, a borderland farmer who spoke no English, did not receive a protection enshrined among our most basic constitutional rights.

He hoped his son would fare better. In 1849, he transferred his entire interest in the property to his son José Antonio. That transfer severed my family’s interest, as we are descended of José Antonio’s brother, Juan Nepomuceno. As it turned out, José Antonio fared worse than his father, fighting not only the federal government for compensation, but others who began to make competing claims that they were the wronged owners. As my research shows, these people would use and abuse every property law tool available to undermine the Salinas claim, so that once compensation was finally offered, it never benefited Salinas’ descendants.

V. Not a Dime

The claims of those falsely asserting ownership of the Salinas property actually derived from the actions of María Francesca Cavazos herself. Simply put, she conveyed the same property twice, to different people. First, she sold it in 1833 to the widow who sold it to Miguel Salinas. Second, her will (administered after she died in 1835) purported to leave the Fort Brown property to her niece, María Josefa Cavazos.[15] Perhaps María Francesca simply forgot to revise her will.

Whatever the explanation, a double conveyance of the same property is not unheard of. Because it happens with some frequency, every state has laws identifying which of the competing claims will prevail. These “recording acts” are a key element in first-year property law courses and tested on the bar exam. Yet I was still surprised to unearth these facts, because the doctrine on the books, dating back to Roman times, would clearly render the Salinas heirs the victors. Nemo dat quod non habet: you cannot convey what you don’t own. Under this principle, recording acts would invalidate the second transfer, because the elder Cavazos no longer owned the property when she died. Moreover, her niece would not have been a “bona fide purchaser” as the acts typically require.

Yet that’s not how it worked out. Instead, the legal battles between successors to the Salinas chain and the María Josefa chain lasted for nearly sixty years. Public attention to these disputes reached a fever pitch in the decade after the war. In 1860, the Texas Supreme Court held that one lawsuit could not even be heard in Cameron County (where Brownsville holds the county seat) because of potential juror bias, reflected in “the formation of processions on both sides, the display of badges and banners, with inscriptions indicative of high feeling against each other… [such that] there is scarcely a citizen residing in the said counties who is not a partisan on one side or the other in this controversy.”[16]

The sordid details are laid out in dozens of judicial decisions, filings, Texas Attorney General opinions, and Congressional committee reports. The Salinas heirs kept filing lawsuits into the 1890s.[17] One name came up again and again: Stillman. Charles Stillman, a Connecticut-born entrepreneur, bought up land in the Rio Grande Valley (including other portions of the Portrero del Espíritu Santo grant). He became one of the richest men in America; his son James worked with him and inherited his various property interests.[18] As their last name suggests, they were White, not Mexican or Mexican-American. They had vast wealth and deep political connections that ultimately helped them acquire legal interests in both strands of the competing claims.

A few facts among many can illustrate how they did it. Stillman’s business partner, Major William Chapman, was quartermaster of Fort Brown when Miguel Salinas first claimed compensation.[19] In 1862, Stillman’s attorney, Stephen Powers, finagled a half-interest in any Salinas property from the son who did inherit it (José Antonio).[20] Then in 1875, Stillman negotiated a half-interest in the property from María Josefa Cavazos (the niece)—then got his associate appointed the administrator of the will to the party who held the other half.[21] Time and again, the historical documents show how Stillman outwitted Cavazos. Another egregious example involved a property near the Salinas tract, for which Stillman negotiated to pay just one-sixth of the value, though it is not clear he ever paid at all.[22]

The Stillmans’ connections likely were crucial in leading a Congressional committee in 1885 to appropriate $160,000 to compensate property owners for the Fort Brown taking.[23] The Secretary of War asked a critical question to the Attorney General of Texas: under state law, who gets the money? After review, the Attorney General suggested that the proceeds be split between Charles Stillman and another of Stillman’s associates. He acknowledged Salinas’s claim for unpaid rent but opined that the unpaid rent should not be compensated by the Congressional grant.[24] Despite trips to the Fifth Circuit[25] and even the Supreme Court of the United States,[26] the Salinas heirs ultimately received nothing. A 1905 visit to the U.S. Supreme Court seemed to end the mess of poorly-reasoned (or at least poorly-explained) decisions. The Court found that once compensation had been distributed to Stillman and his associates, the Court lacked jurisdiction to award a dime to the Salinas-descended claimants.

|

VI. The Seizure’s Long-Lasting Effects

While the Mexican-American War ended in just two years, the Army held on to the Salinas family’s land for a century. The effects of the seizure have lasted much longer. The immediate impacts are obvious. When General Taylor marched on his property, Salinas was a wealthy man. The Congressional committee later investigating the Salinas claim for compensation acknowledged that the seizure “nearly beggared him.”[27] He must have had a little left over, as his children could afford lawyers, however ineffective. Yet that money disappeared when well-educated English speakers triumphed again and again in a legal system that continues to prioritize the interests of the powerful. |

The family’s struggle endured. His great-grandchild, my great-grandmother, lived her ninety-six years in relative poverty a few blocks away from Fort Brown. Her adult life was shadowed by the Salinas land theft. She talked about it often to her children, including my maternal grandmother. At some point, my great-grandmother even traveled to Mexico City with a relative to speak with an ambassador, or perhaps other officials, about the claim. The details of this visit are lost: they died with her. She passed on when I was in college and too ignorant to realize the importance of all the stories I should have been asking her to tell. My great-grandmother’s attachment to the stolen land was so much a part of her identity that her obituary included a reference to Miguel Salinas and his property claim.

While she actively pursued compensation, and felt the loss deeply, later generations have not. They have moved on. But, having spent two years sifting through available accounts, it’s hard for me to put this aside. I am haunted that the only things I know come from public records. I failed to ask questions, failed to display a fraction of the curiosity with which I vigorously tackle my scholarly work. And we have no family heirlooms—like hand-written letters or journals—to fill in the blanks. The storytellers have left us, so their stories will forever evade us.

The only other living person from the hundreds in my large extended family I know to have any active interest in the topic is Bertie. Yet generations were all deeply affected nonetheless, most importantly in their social and economic standing. My grandparents were the first generation to speak English, and my parents were the first generation to finish college.

Things might have been different if the federal government made Salinas whole—giving him the compensation to which, according to the Constitution, he was entitled. In recent years, there has been much talk of reparations being used to right various wrongs, especially those of the nineteenth century. Some Rio Grande Valley residents have asked for reparations stemming from the same types of land grabs my family suffered.[28] Only one family—the Ballís—have had any real success in getting their land back, a story chronicled beautifully by cultural anthropologist Cecilia Ballí.[29] Others, recognizing the reality that such requests are usually fruitless, have given up. The heirs of José Salvador de la Garza, who received the Portrero del Espíritu Santo land grant from the Spanish King, have been reduced to asking for a historical marker on what was once his land.[30]

We may have no choice but to accept the same. The marker I saw last July neither mentions the family displaced by the original taking nor the many other families whose lives changed as fort expansion demanded more land. If compensation would do little for those whose lives have come and gone, shaped and limited in ways known and unknown as a result of that original taking, an acknowledgment of the act would at least honor them with honesty.

Last year, a Congressman from Brownsville proposed, and the House of Representatives passed, legislation that would include Fort Brown within the boundaries of an existing national historical site in Brownsville.[31] The existing site is run by the National Park Service, which, to its credit, has tried to improve the way it interprets complex histories for the public. If the Senate passes that bill too, there will be an opportunity for the Park Service to ensure visitors know that this site had meaning before Zachary Taylor marched on it. Before it provided the military with a strategic position that changed the outcome of the war and that secured the United States’ interests in property from Texas to California. Before it altered the economic trajectory of a still-young nation.

Miguel Salinas’ contributions and concessions should be recognized as a piece of the site’s history more important than earthwork construction techniques. Historic preservation means more than preserving buildings deemed significant. It must mean preserving the stories that give places meaning, and that just might keep us from making the same mistakes again.

While she actively pursued compensation, and felt the loss deeply, later generations have not. They have moved on. But, having spent two years sifting through available accounts, it’s hard for me to put this aside. I am haunted that the only things I know come from public records. I failed to ask questions, failed to display a fraction of the curiosity with which I vigorously tackle my scholarly work. And we have no family heirlooms—like hand-written letters or journals—to fill in the blanks. The storytellers have left us, so their stories will forever evade us.

The only other living person from the hundreds in my large extended family I know to have any active interest in the topic is Bertie. Yet generations were all deeply affected nonetheless, most importantly in their social and economic standing. My grandparents were the first generation to speak English, and my parents were the first generation to finish college.

Things might have been different if the federal government made Salinas whole—giving him the compensation to which, according to the Constitution, he was entitled. In recent years, there has been much talk of reparations being used to right various wrongs, especially those of the nineteenth century. Some Rio Grande Valley residents have asked for reparations stemming from the same types of land grabs my family suffered.[28] Only one family—the Ballís—have had any real success in getting their land back, a story chronicled beautifully by cultural anthropologist Cecilia Ballí.[29] Others, recognizing the reality that such requests are usually fruitless, have given up. The heirs of José Salvador de la Garza, who received the Portrero del Espíritu Santo land grant from the Spanish King, have been reduced to asking for a historical marker on what was once his land.[30]

We may have no choice but to accept the same. The marker I saw last July neither mentions the family displaced by the original taking nor the many other families whose lives changed as fort expansion demanded more land. If compensation would do little for those whose lives have come and gone, shaped and limited in ways known and unknown as a result of that original taking, an acknowledgment of the act would at least honor them with honesty.

Last year, a Congressman from Brownsville proposed, and the House of Representatives passed, legislation that would include Fort Brown within the boundaries of an existing national historical site in Brownsville.[31] The existing site is run by the National Park Service, which, to its credit, has tried to improve the way it interprets complex histories for the public. If the Senate passes that bill too, there will be an opportunity for the Park Service to ensure visitors know that this site had meaning before Zachary Taylor marched on it. Before it provided the military with a strategic position that changed the outcome of the war and that secured the United States’ interests in property from Texas to California. Before it altered the economic trajectory of a still-young nation.

Miguel Salinas’ contributions and concessions should be recognized as a piece of the site’s history more important than earthwork construction techniques. Historic preservation means more than preserving buildings deemed significant. It must mean preserving the stories that give places meaning, and that just might keep us from making the same mistakes again.

|

Title: Professor, Cornell University

Bio: Sara Bronin is a Mexican-American, seventh-generation Texan, architect, attorney, and professor of planning and law at Cornell University. Among other public service, she founded the National Zoning Atlas and Desegregate Connecticut. She is the author of the forthcoming book, Key to the City, about land use law. |

Footnotes

[1] See “Senate Resolution No. 719,” Texas Legislature Online. https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/85R/billtext/html/SR00719F.htm; “Bertha Lucia Caballero, Brownsville,” Houston Chronicle. https://www.chron.com/news/houston-texas/article/Bertha-Lucio-Caballero-Brownsville-1869070.php.

[2] See “Cameron County,” Texas State Historical Association Handbook of Texas. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/cameron-county.

[3] Several scholars have discussed land grants. Robert V. Urias (“The Tierra Amarilla Grant, Reies Tijerina, and the Courthouse Raid.” Chicana/o Latina/o Law Review 16, no. 1 (1995)) argued that “the poverty and disillusionment of the people in Tierra Amarilla is related to their inability to obtain land rights” after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Christine A. Klein (“Treaties of Conquest: Property Rights, Indian Treaties, and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo," New Mexico Law Review 26, no. 201 (1996)) compares the property rights of Indians after Native American treaties and the property rights of former Mexican property owners after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, noting that the formerly Mexican properties were less protected and could be lost by non-use. Guadalupe T. Lunda, (“Chicana/Chicano Land Tenure in the Agrarian Domain: On the Edge of a ‘Naked Knife,’” 4 Michigan Journal of Race & Law 39 (1998)) observes that the United States did not meet its obligations under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which promised to protect the land interests of Mexican land grantees. Jon Michael Haynes (“What Is It About Saying We’re Sorry? New Federal Legislation and the Forgotten Promises of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo,” The Scholar: St. Mary’s Law Review on Minority Issues 3, no. 231 (2001)) argues the adjudication and legislation involving Mexican and Spanish land grants was unjust and will never be resolved and notes legislation introduced in Congress to have the GAO issue a report to the President about actions taken by the federal government and the Territory of New Mexico.

[4] The grant was described in a case, Cavazos v. Trevino, 73 U.S. 773 (1867). See also United States House of Representatives, House Documents (Washington: James B. Stedman, 1858): 690, https://bit.ly/3K1qT1E. House Documents identifies Don Francisco Xavier Gamboa as the special judge for the sale and disposition of lands and waters in the viceroyalty of New Spain.

[5] See Cavazos v. Trevino, 35 Tex. 133, 134-135 (1871).

[6] Carl S. Chilton, Jr., Fort Brown: The First Border Post 71 (2005) (Share 22); House Documents, supra n. 4, at 691.

[7] Gloria Ricci Lothrop (“Rancheras and the Land: Women and Property Rights in Hispanic California, Southern California Quarterly 76, no. 59 (1994)) discusses property rights given to women colonizing California; Texas General Land Office, “Women as Land Owners on the Mexican Frontier: María Calvillo’s Story,” May 28, 2015, https://bit.ly/3fgxjfs.

[8] See Official Opinions of the Attorney General of the United States, within Miscellaneous Documents of the House of Representatives: First Session of the Fifty-First Congress 1889-’90. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891), 334, https://bit.ly/3qgj2p3.

[9] Chilton, supra n. 6, at 71; see also Official Opinions, supra n. 8, at 334. https://bit.ly/3qgj2p3. The holder of the property between Cavazos and Salinas was the Escamilla family.

[10] Congressional Committee on War Claims, Bill H.R. 1417, H.R. Report No. 123 (Feb. 5, 1892).

[11] Ibid

[12] See Carson v. Combe, 86 F. 202, 203 (5th Cir. 1898).

[13] Texas State Historical Association, “Land Grants.” https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/land-grants.

[14] Congressional Committee on War Claims, supra n. 10 (publishing relevant portions of the letter, dated September 7, 1849).

[15] Eugene Fernandez, “The Complexity of Land Custody in 19th Century Deep South Texas,” in New Studies in Rio Grande Valley History, Milo Kearney et al. (University of Texas Rio Grande Valley and Texas Southmost College: 2018), 37. Fernandez describes how share #22 ended up with Jose Salvador’s grandniece, María Josefa Cavazos.

[16] Salinas v. Stillman, 25 Tex. 12 (1860)

[17] Salinas v. Stillman, 66 F. 677 (5th Cir. 1894).

[18] “Stillman, Charles (1810-1875),” Texas State Historical Association Handbook of Texas. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/stillman-charles; Elim Zavala, “Place Identity Formation in the Lower Rio Grande Valley: The Identity of Brownsville, Texas,” in New Studies in Rio Grande Valley History, Milo Kearney et al. (University of Texas Rio Grande Valley and Texas Southmost College: 2018), 11.

[19] Fernandez, supra n. 15.

[20] Official Opinions, supra n. 8, at 334.

[21] Charles was dead by the time the Attorney General weighed in, though he was represented by James Stillman. James Stillman claimed not only the half-interest of Charles, but the full interest on the basis of tax deeds.

[22] The Texas State Historical Association says, however: “Although the Garza heirs won their case [this may have had something to do with the legislative repeal of the first charter of the City of Brownsville in January 1852, referred to in the 1871 Brownsville v. Basse & hord case] in January 1852, they sold the Brownsville tract the following April for one-sixth of its appraised value to the lawyers who had represented Stillman, and Stillman subsequently acquired the property.” See https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fga92. Texas State Historical Association Almanac, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/garza-falcon-María-gertrudis-de-la; Fernandez, supra n. 15, at 39 (confirming the deflated price Stillman used for the purchase).

[23] See Official Opinions, supra n. 8, at 328. On March 3, 1885 [Chapter 360], a Congressional act appropriated $160,000 “to enable the Secretary of War to acquire good and valid title for the United States to the Fort Brown Reservation, Tex., and to pay and extinguish all claims for the use and occupation of said reservation by the United States,” with a proviso “that no part of said sum shall be paid until a complete title is vested in the United States, and that the full amount of the price, including rent, shall be paid directly to the owners of the property.”

[24] Official Opinions, supra n. 8, 343. “This claim does not, I think, come within the scope of the appropriation made by the act of March 3, 1885.”

[25] Carson v. Combe, supra n. 12.

[26] Stillman v. Combe, 25 S.Ct. 480 (1905). There is also a reference in Official Opinions, supra n. 8, at 344, stating that Charlotte Miller asserted a claim in 1856 under the Powers’ line.

[27] Congressional Committee on War Claims, supra n. 10.

[28] Rose Richerson, “Spanish and Mexican Land Grants and Heirs’ Rights to Unclaimed Mineral Estates in Texas,” Texas A&M Journal of Real Property Law 2, no. 97 (2014); “Family Sues Texas Over Centuries-Old Spanish Land Grant,” NBC Dallas-Fort Worth. https://www.nbcdfw.com/news/local/family-sues-texas-over-centuries-old-spanish-land-grant/157673/.

[29] Cecilia Ballí, “Return to Padre,” Texas Monthly, Jan. 2001.

[30] “Descendants Seek Marker for Espiritu Santo Land Grant,” Juan Montoya. https://rrunrrun.blogspot.com/2017/10/historical-marker-sought-for-espiritu.html.

[31] H.R. 268, “To provide for the boundary of the Palo Alto Battlefield National Historic Park to be adjusted, to authorize the donation of land to the United States for addition to that historic park, and for other purposes.”

[2] See “Cameron County,” Texas State Historical Association Handbook of Texas. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/cameron-county.

[3] Several scholars have discussed land grants. Robert V. Urias (“The Tierra Amarilla Grant, Reies Tijerina, and the Courthouse Raid.” Chicana/o Latina/o Law Review 16, no. 1 (1995)) argued that “the poverty and disillusionment of the people in Tierra Amarilla is related to their inability to obtain land rights” after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Christine A. Klein (“Treaties of Conquest: Property Rights, Indian Treaties, and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo," New Mexico Law Review 26, no. 201 (1996)) compares the property rights of Indians after Native American treaties and the property rights of former Mexican property owners after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, noting that the formerly Mexican properties were less protected and could be lost by non-use. Guadalupe T. Lunda, (“Chicana/Chicano Land Tenure in the Agrarian Domain: On the Edge of a ‘Naked Knife,’” 4 Michigan Journal of Race & Law 39 (1998)) observes that the United States did not meet its obligations under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which promised to protect the land interests of Mexican land grantees. Jon Michael Haynes (“What Is It About Saying We’re Sorry? New Federal Legislation and the Forgotten Promises of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo,” The Scholar: St. Mary’s Law Review on Minority Issues 3, no. 231 (2001)) argues the adjudication and legislation involving Mexican and Spanish land grants was unjust and will never be resolved and notes legislation introduced in Congress to have the GAO issue a report to the President about actions taken by the federal government and the Territory of New Mexico.

[4] The grant was described in a case, Cavazos v. Trevino, 73 U.S. 773 (1867). See also United States House of Representatives, House Documents (Washington: James B. Stedman, 1858): 690, https://bit.ly/3K1qT1E. House Documents identifies Don Francisco Xavier Gamboa as the special judge for the sale and disposition of lands and waters in the viceroyalty of New Spain.

[5] See Cavazos v. Trevino, 35 Tex. 133, 134-135 (1871).

[6] Carl S. Chilton, Jr., Fort Brown: The First Border Post 71 (2005) (Share 22); House Documents, supra n. 4, at 691.

[7] Gloria Ricci Lothrop (“Rancheras and the Land: Women and Property Rights in Hispanic California, Southern California Quarterly 76, no. 59 (1994)) discusses property rights given to women colonizing California; Texas General Land Office, “Women as Land Owners on the Mexican Frontier: María Calvillo’s Story,” May 28, 2015, https://bit.ly/3fgxjfs.

[8] See Official Opinions of the Attorney General of the United States, within Miscellaneous Documents of the House of Representatives: First Session of the Fifty-First Congress 1889-’90. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891), 334, https://bit.ly/3qgj2p3.

[9] Chilton, supra n. 6, at 71; see also Official Opinions, supra n. 8, at 334. https://bit.ly/3qgj2p3. The holder of the property between Cavazos and Salinas was the Escamilla family.

[10] Congressional Committee on War Claims, Bill H.R. 1417, H.R. Report No. 123 (Feb. 5, 1892).

[11] Ibid

[12] See Carson v. Combe, 86 F. 202, 203 (5th Cir. 1898).

[13] Texas State Historical Association, “Land Grants.” https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/land-grants.

[14] Congressional Committee on War Claims, supra n. 10 (publishing relevant portions of the letter, dated September 7, 1849).

[15] Eugene Fernandez, “The Complexity of Land Custody in 19th Century Deep South Texas,” in New Studies in Rio Grande Valley History, Milo Kearney et al. (University of Texas Rio Grande Valley and Texas Southmost College: 2018), 37. Fernandez describes how share #22 ended up with Jose Salvador’s grandniece, María Josefa Cavazos.

[16] Salinas v. Stillman, 25 Tex. 12 (1860)

[17] Salinas v. Stillman, 66 F. 677 (5th Cir. 1894).

[18] “Stillman, Charles (1810-1875),” Texas State Historical Association Handbook of Texas. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/stillman-charles; Elim Zavala, “Place Identity Formation in the Lower Rio Grande Valley: The Identity of Brownsville, Texas,” in New Studies in Rio Grande Valley History, Milo Kearney et al. (University of Texas Rio Grande Valley and Texas Southmost College: 2018), 11.

[19] Fernandez, supra n. 15.

[20] Official Opinions, supra n. 8, at 334.

[21] Charles was dead by the time the Attorney General weighed in, though he was represented by James Stillman. James Stillman claimed not only the half-interest of Charles, but the full interest on the basis of tax deeds.

[22] The Texas State Historical Association says, however: “Although the Garza heirs won their case [this may have had something to do with the legislative repeal of the first charter of the City of Brownsville in January 1852, referred to in the 1871 Brownsville v. Basse & hord case] in January 1852, they sold the Brownsville tract the following April for one-sixth of its appraised value to the lawyers who had represented Stillman, and Stillman subsequently acquired the property.” See https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fga92. Texas State Historical Association Almanac, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/garza-falcon-María-gertrudis-de-la; Fernandez, supra n. 15, at 39 (confirming the deflated price Stillman used for the purchase).

[23] See Official Opinions, supra n. 8, at 328. On March 3, 1885 [Chapter 360], a Congressional act appropriated $160,000 “to enable the Secretary of War to acquire good and valid title for the United States to the Fort Brown Reservation, Tex., and to pay and extinguish all claims for the use and occupation of said reservation by the United States,” with a proviso “that no part of said sum shall be paid until a complete title is vested in the United States, and that the full amount of the price, including rent, shall be paid directly to the owners of the property.”

[24] Official Opinions, supra n. 8, 343. “This claim does not, I think, come within the scope of the appropriation made by the act of March 3, 1885.”

[25] Carson v. Combe, supra n. 12.

[26] Stillman v. Combe, 25 S.Ct. 480 (1905). There is also a reference in Official Opinions, supra n. 8, at 344, stating that Charlotte Miller asserted a claim in 1856 under the Powers’ line.

[27] Congressional Committee on War Claims, supra n. 10.

[28] Rose Richerson, “Spanish and Mexican Land Grants and Heirs’ Rights to Unclaimed Mineral Estates in Texas,” Texas A&M Journal of Real Property Law 2, no. 97 (2014); “Family Sues Texas Over Centuries-Old Spanish Land Grant,” NBC Dallas-Fort Worth. https://www.nbcdfw.com/news/local/family-sues-texas-over-centuries-old-spanish-land-grant/157673/.

[29] Cecilia Ballí, “Return to Padre,” Texas Monthly, Jan. 2001.

[30] “Descendants Seek Marker for Espiritu Santo Land Grant,” Juan Montoya. https://rrunrrun.blogspot.com/2017/10/historical-marker-sought-for-espiritu.html.

[31] H.R. 268, “To provide for the boundary of the Palo Alto Battlefield National Historic Park to be adjusted, to authorize the donation of land to the United States for addition to that historic park, and for other purposes.”

7/8/2022

|

Comment Box is loading comments...

|

|